“The Edge of Seventeen,” a 2016 film by Kelly Fremon Craig released to critical acclaim, feels increasingly personal with every rewatch. It’s an under-appreciated dramedy classic for a new generation of teenage girls and a movie with the unlikely aspiration to understand its young female protagonist instead of lampooning her.

Hailee Steinfeld was a Golden Globe nominee for her performance as high school junior Nadine, who is already reeling from the ups and downs of teenage life when her older brother Darian (Blake Jenner) and her best friend Krista (Haley Lu Richardson) suddenly start dating. Nadine is not happy about it, to say the least.

The circumstances cause Nadine’s relationships with both sibling and friend to implode, which sets off a chain of collateral effects elsewhere in her life: She starts acting out and pissing off her mom, pursues an enigmatic senior, finds a new friend in classmate Erwin (Hayden Szeto) and turns to her teacher Mr. Bruner (Woody Harrelson) as an unexpected confidant.

The film is a brilliant glimpse of the way relationships can flex, tense and evolve, and I don’t think enough people have seen it.

At its essence, “The Edge of Seventeen” is a movie about those relationships. Although Steinfeld’s portrayal of Nadine is what propels it to classic status, the film graces its audience with a supporting cast of well-developed characters.

There’s no need for an outright antagonist because much of the conflict stems from the reality that not everyone in Nadine’s life exists to serve her interests. They aren’t villains hell-bent to wreak havoc on her; people just don’t always see eye to eye, whether they’re daughter and mother, sister and brother or friend and friend.

You don’t need to look further than Nadine’s own family for shining examples of this. Her mother, Mona, (the inimitable Kyra Sedgwick) is depressed by her husband’s death, deeply frustrated by her daughter and quells her anxieties through periodic reminders that everyone else is “just as miserable as [she] is.”

Darian, whose life appears picture-perfect to Nadine, is trapped by his mother’s dependence on him to take his dad’s place in the household. In fact, he only applies to colleges in-state so he wouldn’t be too far from home after graduation.

The audience can sense the burdens early on, and Mona and Darian reveal them as Nadine’s walls crumble and leave her exposed to her loved ones’ struggles.

“I think some deranged part of me likes thinking I’m the only one with real problems,” Nadine tells Darian. It’s an honest revelation that stands out in a film with many.

“The Edge of Seventeen” departs from a longstanding cinematic tradition in which teen girls are vaguely sociopathic creatures, out to serve their own shallow interests at the expense of just about everyone else.

Although it might be easy for some filmmakers to paint the teenage girl as an antagonist, it’s equally true that positive portrayals don’t need to be utopian to be valid.

This sort of hunger for varied representation has been proven most recently with the success of films such as “Lady Bird” and “Thoroughbreds,” both stories about complex teenage girls. Unfortunately, this didn’t stop Netflix from releasing the inept, brain-dead “The Kissing Booth” last month, a movie which goes to great lengths to turn its female lead into a caricature.

Such caricatures are ridiculed in “The Edge of Seventeen,” like when Nadine is embarrassed for stereotyping her friend Erwin’s Korean parents and then again for wrongly assuming that Mr. Bruner is an unmarried loner with a low pay grade.

Nadine herself leans hard into an alt-persona that many would be quick to dismiss. Everyone knows someone who’d gripe that their “entire generation is a bunch of mouth-breathers,” as Nadine does, even if it seems like an obnoxious thing to say. Sometimes people can be predictable without regressing to parody.

Another triumph of “The Edge of Seventeen” lies in its portrayal of Nadine’s sexuality, which is never gratuitous or forced. It is so rare to find a film that acknowledges a young female lead’s sexuality without degrading them for it or using it to provoke male desire.

In a scene where Nadine and her crush are hooking up, she calls the shots, changing her mind about what they’re doing as she sees fit. She gives consent, revokes it, gives it back, then finally decides she wants to leave and all of this is normal and OK.

The guy ends up being a total asshole of course, but the film never once implies that this is Nadine’s fault. She’s entirely in charge.

The film’s subtle sexual politics don’t stop there. It’s worth noting that Nadine and Krista are clearly at two different stages of their sex lives, but this isn’t a factor in the conflict that arises between them. There’s no pressure or competition in their friendship.

There’s also no enforcement of a sexual bipolarity, where girls are either prudes or whores and nothing else. Nadine has never had sex, but she can still flirt, send salacious texts and do virtually whatever she wants to do without compromising her level of comfort.

“The Edge of Seventeen” refreshes the coming-of-age genre by portraying its lead within the context of her life, rather than as the detached subject of a story in which she is the ends to a means. Really, how often is the entire picture of a teen girl’s life shown on-screen?

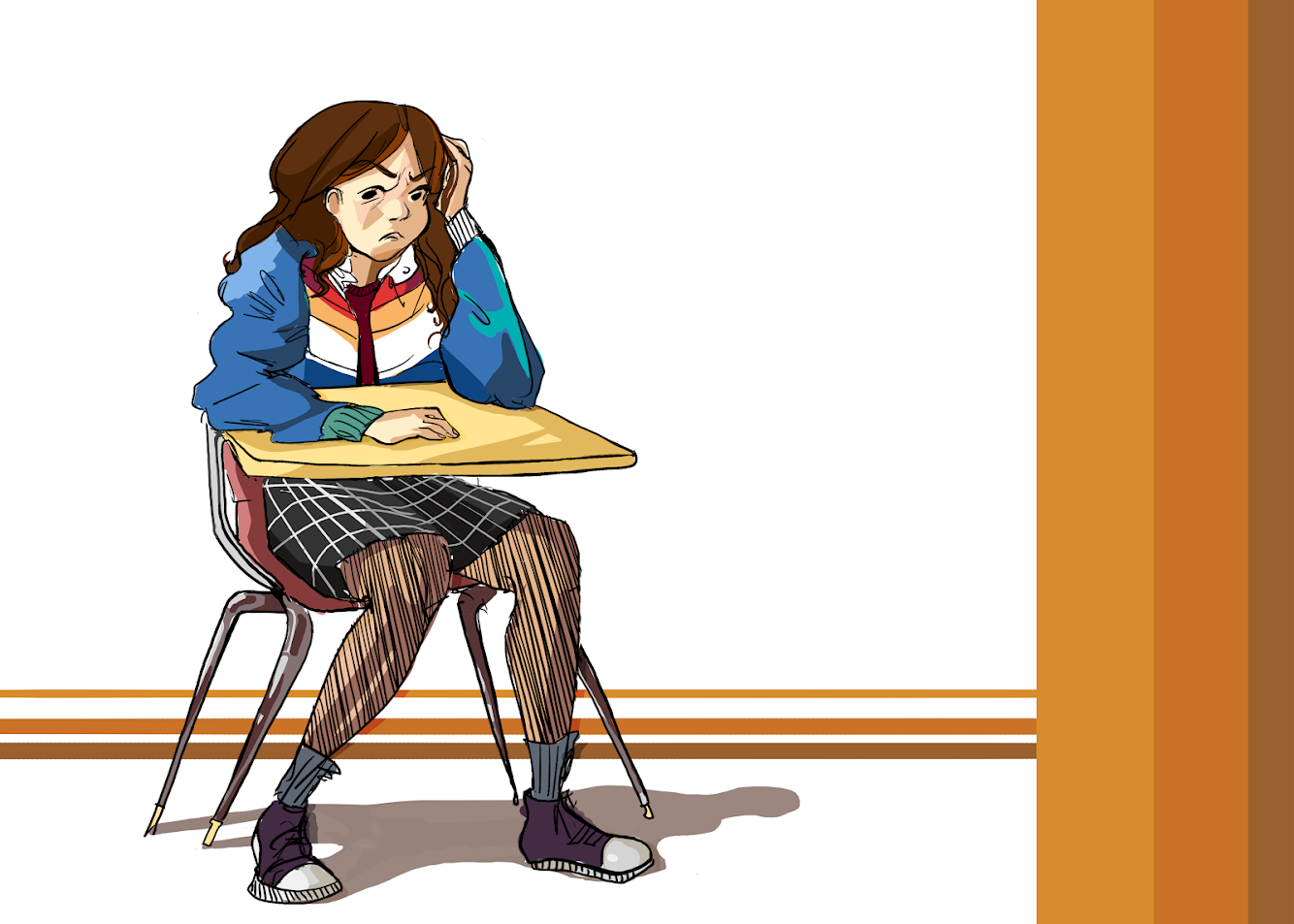

Throughout the film, Nadine can be seen at home, in school, at parties, by herself, with a teacher, with a hookup, with family, with friends. No matter where Nadine goes, she retains the essence of her being. She’s not just a character serving a story.

Nadine is deeply self-reflective. This is a privilege not always afforded to teen girls on screen, especially when it’s easier to make them look like they’ve never contemplated anything at all.

One night, Nadine drunkenly sobs to Krista, “Why am I so grotesque? How do you even like me?” She constantly looks inward for shortcomings and then seeks external validation of her findings. She loves her family and friends and doesn’t want to be the one that pushes them away.

After all, Nadine is a product of the people who surround her. As she navigates the trenches of adolescence, each of her relationships gives insight into who she is and what she’ll do next.

She has a tough relationship with her mom, a testy one with Darian and a loving one with Krista. And yet, for all of these convenient, reductive descriptors, each connection has real-life texture and depth.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EB6Gecy6IP8

Nadine feels love, hate, annoyance, adoration, apathy — many of which are conveyed in lone expressions — because relationships rarely rest on a single feeling. Her impulses and choices are an echo of the adolescent rationale, where stakes are perpetually heightened because it seems like other people are always watching and listening.

There is one scene where she wanders around at a party, hovering at the edges of other people’s conversations. Darian and Krista are somewhere in the center of it all, and Nadine is on the periphery, an outsider looking in.

To appear busy, she stares intently at the family photos on the walls of the host’s home. Then she escapes to the bathroom to give herself a pep talk, angrily huffing at her reflection, “God, why are you so awkward?” Those images will be vivid reminders to anyone who has had similar insecurities.

Nadine can be selfish, cruel and stubborn. These are not characteristics to be proud of, but they also aren’t the defining traits of teenage girls. They are puzzle pieces in the makeup of the human being.

The movie never hides or excuses Nadine’s bad behavior. In fact, it calls her out for her transgressions, because for better or for worse, her behavior is universal to all human beings. Yes, humans are imperfect, and in “The Edge of Seventeen,” Nadine is nothing if not gorgeously, utterly and authentically human.