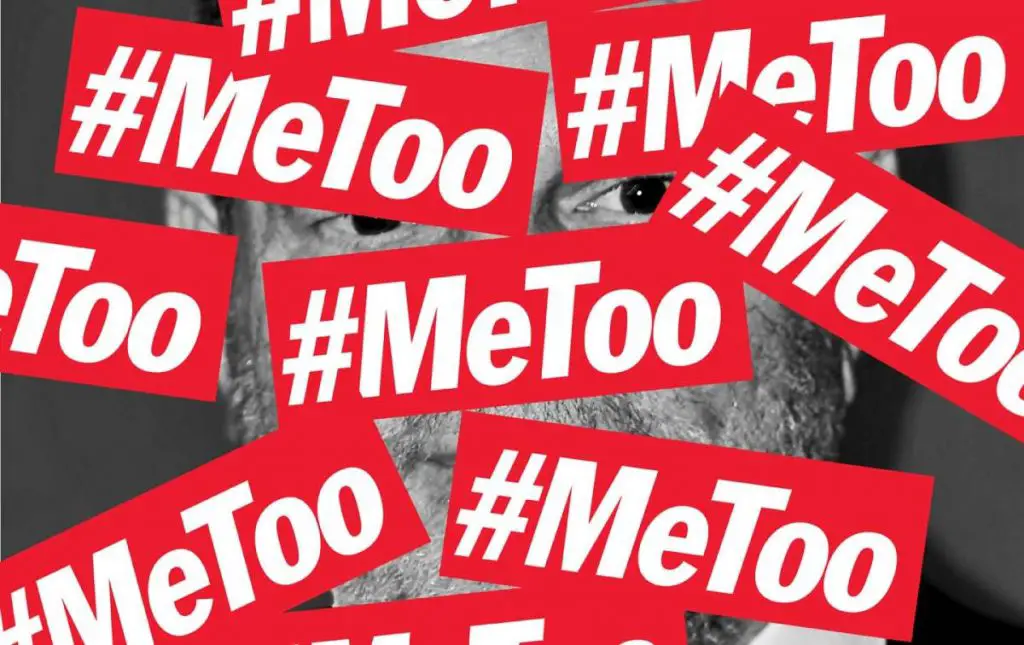

The #MeToo movement is the biggest current cultural phenomenon, sparking controversy and a tidal wave of change everywhere from the film industry to the news world, the Olympic arena and the White House. It’s the reason why celebrities wore black at the Golden Globes and white roses at the Grammys.

It’s why the 2017 TIME person of the year was the ‘Silence Breakers,’ and why companies like NBC have been forced to reconsider their choice of employees. In many ways, it has become an impossible force to criticize –—unless you want to look like a chauvinist.

Recently, 100 French women challenged that notion. An open letter published in the French newspaper Le Monde speaks out against the movement. Leading the charge is actress Catherine Deneuve, the grand dame of the French film scene. She joins actress Christine Boisson, journalist Élisabeth Lévy, magazine editor Catherine Millet and a host of other women in their criticisms of #MeToo and the French version #balancetonporc (French for “squeal on your pig”).

“Rape is a crime,” the letter begins, “but trying to pick up someone, however persistently or clumsily, is not.” The opening paragraphs of the letter acknowledge the legitimate good of speaking out when men abuse their power.

However, the women say “what was supposed to liberate voices has now been turned on its head.” The movement that “claims to promote the liberation and protection of women” in reality has only “enslave[d] them to a status of eternal victim and reduce[d] them to defenseless prey of male chauvinist demons.”

The letter argues that the frenzy of the #MeToo campaign has led to accusations that immediately label men as villains without giving them a chance to defend themselves. Further, the women say that the movement has become unnecessarily pervasive, going so far as to play a role in whether or not a museum should display a certain work, or a university should play a certain movie.

This argument serves as a reminder that, while the United States criminal justice system practices the mandate of innocent until proven guilty, #MeToo has all too often censured men the moment they are accused, setting them on a path of destruction with little hope for atonement. In the workplace, the letter notes, men have been summarily ousted when their only crime was “to touch a woman’s knee, try to steal a kiss, talk about ‘intimate’ things during a work meal.”

The discussion of workplace sexual harassment leads to the second point of the letter: the freedom to bother. In a nutshell, the authors claim men’s right to hit on women as essential to sexual freedom.

The statement explains that a woman’s freedom to say no to a sexual proposition can’t exist without this freedom to bother. “We consider that one must know how to respond to this freedom to bother in ways other than by closing ourselves off in the role of the prey,” the letter says.

The letter gained widespread interest and strong reactions. Some people welcomed the letter as a pushback against America’s seemingly excessive brand of feminism, which the letter argues has driven us to an era of “puritanism.”

Meanwhile, a group of French feminists, led by Caroline De Hass, penned a dissenting response, saying “The signatories of the Le Monde article are deliberately confusing a relationship of seduction, based on respect and pleasure, with violence. To mix everything is quite practical. It allows everything to go into one basket. If harassment or aggression are ‘heavy flirting’ then it’s not too serious. The signatories are wrong.”

Many American news outlets chose to highlight the difference in culture between France and the United States, noting that the French place less emphasis on sexual taboos. The French entrepreneur Raphael Hun took a similar view and commented on USA Today that “there is a part of our (French) culture where seducing is important and well-regarded.”

Even SNL took on the issue. A new skit stars Cecily Strong as Catherine Deneuve, saying she didn’t want “romance to die” and that people should have the freedom to explore and enjoy sex. So what to make of the letter? Has the #MeToo movement really gone too far?

On the one hand, Deneuve and her fellow authors point out something important: we as a society must be well-versed in the differences between flirting, consent and sexual harassment, especially as they play a prominent role in our daily lives. Colleges wrestle with this topic every day, as they mandate online courses and seminars meant to build a shared understanding of sexual boundaries.

The subject also caught public attention in early January, when a woman by the pseudonym of Grace wrote to Babe magazine accusing the comedian Aziz Ansari of sexual assault on their date. His defenders claim that she never verbally made her discomfort clear and that while his behavior certainly may have been boorish, it was not sexual assault.

Nevertheless, the letter tarnished the actor’s reputation, despite his public apology. The reader is left wondering where we’re supposed to draw the line.

On the other hand, critics of the letter claim that it trivializes sexual assault. The letter talks about men who have been fired for unwelcome advances at work as if their inappropriate behavior were simply minor offenses by men who didn’t know better.

It says that women should dismiss a man rubbing himself on her in a public bus as a “non-event” or simply the man’s expression of sexual deprivation. It says that men shouldn’t understand how grossly unacceptable that is. To the many critics, this behavior doesn’t fall under the freedom to bother.

The letter is just one example of how our society’s dialogue about sexual harassment has shifted within the last few months. In some ways, the line between what is acceptable and not-acceptable between men and women is clearer than ever. Women feel more empowered to call out men who act inappropriately toward women, regardless of the men’s wealth or power.

In other ways, however, the line is blurrier than ever. Sexual assault is never acceptable, but what is the line between what one person thinks is flirting and what another perceives as overly aggressive?

Is it a matter of verbally announcing one’s discomfort? Of changing the idea in our culture that a man should attempt seduction until a woman says no? Is it ethical to publicly accuse men of sexual harassment without first vetting the facts?

To answer these questions, the world engages in constant dialogue as its biggest stars speak out and its organizations undergo policy changes. However, the problem of where to draw the line doesn’t end in Hollywood. On college campuses, the issue is no less important, as it directly pertains to the dating and hookup culture which surrounds us every day. All the more reason why students should stay engaged with the topic and perhaps start a dialogue of their own.