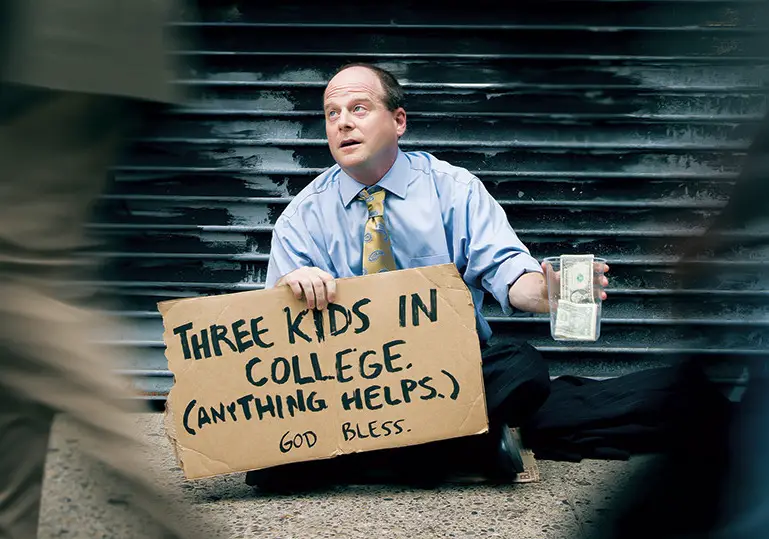

If you’re a college student, you know that tuition is anything but cheap. The cost of college is only rising, and with that rising price comes market competition. As in any other industry, colleges and universities have to compete with one another for both student enrollment and student quality. To attract top students and stay competitive, colleges have had to invest heavily in marketing campaigns.

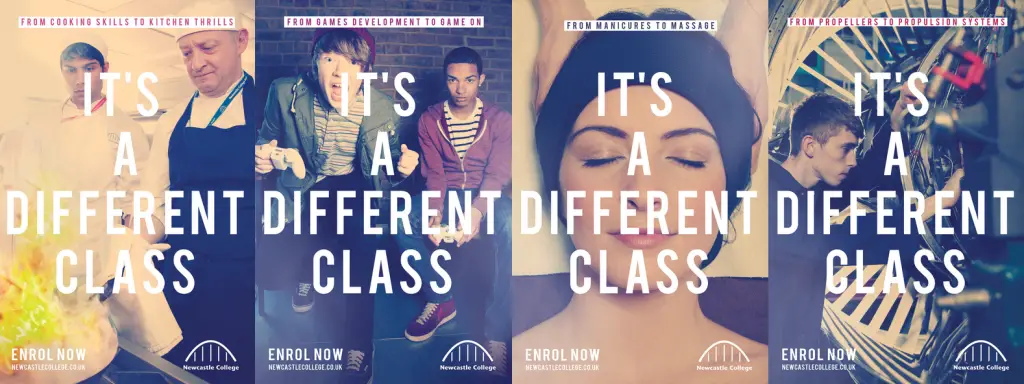

These days, branding, or rebranding, is everything, and there is extreme pressure to stand out from the crowd with the cleanest logo, simplest tagline and, most importantly, the happiest, most successful looking students. Universities often have to peddle the idea of a “college experience” itself, the kind that includes access to top-notch faculty and staff, exclusive internship and research opportunities and a bubbly social life. They are, in a sense, selling students the future selves they hope to be.

It’s a tall order: to market a school in an effective way to a giant a population of high school students, all with different priorities and interests and hopes about the future institution they’ll attend. Beyond the task, though, is the question of how effective giant marketing campaigns truly are for large institutions and whether the money spent on them actually benefits students, or could be better used elsewhere.

Confusion Over Competition

The first problem for universities is to understand which institutions they are competing with (and which one’s they’re able to compete with). In a 2013 Forbes article, Roger Dooley cites several different subsets of the college market. There’s national schools, which are known either for their prestige (think Ivy Leagues) or for their nationally-ranked sports teams.

Then there are niche schools, which are known within a certain industry or degree area — institutions famous for their art school or engineering school. Regional and local schools occupy the final tier. Regionals are well-known within their state or region of the country, and local schools are usually small, but known for their affordability and easy location.

The problem with these different tiers is that the schools in all categories are often trying to compete for the same students, despite the fact that they are all on much different playing fields. As Dooley says in his article, “Historically, college brands have taken decades, or even centuries, to develop — it’s no accident that many of the most prestigious universities in the U.S. can trace their origins back to the eighteenth century.”

While it is hard for any school to compete with the centuries-long image of Harvard or Yale, it is especially hard for schools in the middle tier. National institutions have the pull of name recognition to trump their rising costs, and affordable regional or local colleges have the clear advantage of saving college students money and resources. Without any of these factors to clearly define themselves, mid-range schools face a tough quest of developing a clear brand message and make it stick.

Effective Brands Aren’t Quick and Easy

Even when mid-range schools are able to develop a brand, it can be hard for that brand to gain any real meaning or weight behind it. Writing for The Chronicle of Higher Education, Steve Kolowich says, “Colleges are built on words…but when it comes to a selling a college’s image, officials have room only for words that will fit on a brochure, or a billboard, or a banner. The result is a genre of marketing rhetoric that is lofty, predictable, and numbing.” Universities that don’t have a clear historic brand message or “thing” they’re known for tend to spend exorbitant amounts of money on branding, but the branding itself can only get you so far.

Recently, Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, spent around $930,000, according to The Daily News, on a new brand campaign. The brand included a new tagline, “We Fly,” a new video campaign and new marketing materials promoting the brand. Much of the cost was dedicated to brand research that gathered data on what people with connection to the community thought about Ball State. While it’s still unclear whether the brand change will be effective in increasing enrollment, there’s an inherent problem in thinking that a slogan by itself can make huge changes.

In the same Chronicle of Higher Education article, Kolowich arranges eighty-eight college slogans into a poem to show the blandness of language and overall forget-ability of most college slogans. While universities without a cohesive brand need some kind of strategy, pouring extra money into new advertising over other areas of development may not always be the key to increasing enrollment.

Investing in Other Areas

The rising price of college makes the market more competitive, but more importantly, it raises the bar for general for students to attend college. In a 2017 article, USA Today College reports that colleges “appear to be increasing their tuition rates by nearly double the inflation rate — a trend that has been consistent for the past decade.” Rising education costs have everyone worried and have even caused political debate; 2016 presidential candidate Bernie Sanders was especially popular among young people for his position that college tuition be free.

Even if college prices aren’t going down anytime soon, inflation makes it more important than ever that institutions are using their money in responsible ways that benefit all students, both current and prospective. On the James. G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal, senior UNC Chapel student Alex Contarino was especially concerned about the amount of money colleges spend on marketing: “Administrators find it easy to justify these wasteful marketing expenses by claiming they will improve their school’s image or increase enrollment. But as state-run institutions, public universities should work to be better stewards of taxpayer money.”

Contarino was talking specifically about public universities, and obviously his opinion on the effectiveness of marketing campaigns is a little biased. But his sentiment is one echoed by many college students who are weary of institutions that charge high tuition prices and fail to invest more in programs, facilities and faculty than they do in advertising. Perhaps, to establish a “centuries-old” brand like that of the country’s most prestigious schools, it would be wiser for universities to take the long view and invest in their programs and academics more than they do in recruiting the outside community.

Though slow, it may be the best path to a college brand that has real staying power.