Let’s be real: Anxiety has never been higher than it is right now, and we could all use a crash course in a tried-and-true way to calm down. There are literally hundreds of online resources created with the intention of calming us down in an age of uncertainty and information overload.

If you need to be distracted by something mindless and creative, you can turn to websites like weavesilk.com, where you can block things out in favor of making art. Or if you need some free advice from real people, 7cups is the website for you.

In an increasingly global world — a characteristic with catastrophic consequences that we are all currently witnessing — it’s incredible to see so many people who are dedicated to helping others survive the day. But I wanted to focus on something a little older, a little more direct, something you don’t need a Wi-Fi connection to use: pranayama.

My mother, Asha, is a certified yoga and meditation therapist who operates out of the East Bay Area, and she’s the first person that got me thinking about the concept of pranayama as a viable anti-anxiety practice. There is, of course, no real cure for anxiety or stress — global pandemic aside, it sometimes feels as though humans are wired to fixate on the negative in our lives.

The point is learning how to deal with anxiety and stress, especially when it appears in smaller, non-clinical forms. And pranayama, an ancient form of meditation that Asha teaches, is a way of tackling chaotic minds and situational anxiety. I interviewed her regarding her views on this practice and the philosophy behind it and found that she had some interesting things to say.

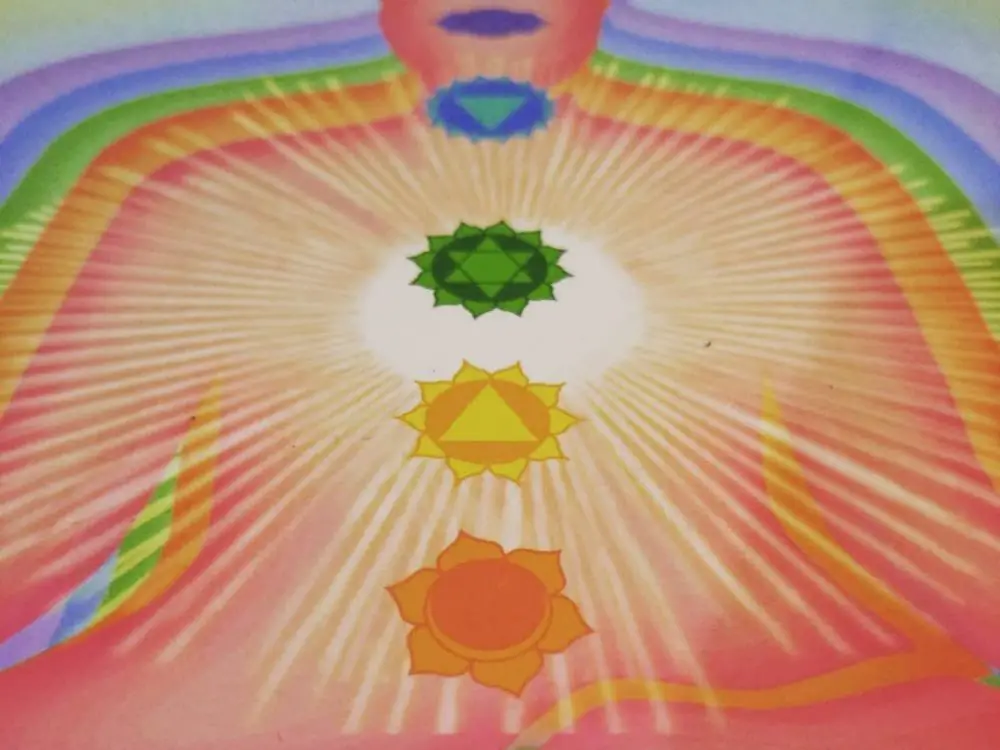

Pranayama is one of eight branches or limbs of yoga, or “Ashtanga.” Together, these eight branches make one composite spiritual practice, the ultimate goal of which is enlightenment (otherwise known as Samadhi). The cycle, sometimes analogized by way of a wheel with eight spokes, is all about centering the self and the thoughts.

The cycle begins with Yama, which is “outer cleansing,” and is followed by Niyama, “inner cleansing.” Both of these involve the removal of outside forces on the body and mind. The third spoke is Asana; this is yoga.

The practice of doing yoga is just one aspect of Ashtanga and, according to Asha, it’s a conscious way of “removing pain” from the body, stretching out the muscles to relax and loosen them. This in itself is a form of meditation that is focused on physical tension. Relaxing and unwinding your muscles is a direct way to deal with the manifestations of anxiety and stress.

Following Asana is pranayama, which is not quite meditation or prayer itself; rather, it is “a prelude to meditation.” The following three spokes, Pratyahara (consciously using the senses), Dharana (focusing and concentrating with the mind) and Dhyana (meditative absorption), bring your attention further and further inward into a deep state of meditative tranquility, culminating in enlightenment.

Suffice it to say that this is all pretty ideal. No one these days has time for enlightenment between meetings, classes and crucial Netflix-watching downtime, the antithesis of a conscious, meditative state.

But pranayama can be extricated from the web of Hindu yogic complexity and turned into something small and actionable. According to Asha, pranayama is actually “nothing but conscious breathing.”

She explains: “We’re always breathing but it’s unconscious. When we breathe consciously, we’re trying to control the amount of air we’re taking in and expelling.” The practice is nothing more than a conscious breathing exercise, a momentary shifting of attention to the functions of the body.

The key word here is “momentary.” The versatility of pranayama lies in its sole requirement — concentration on the breath. This means you can do it for just 10 seconds, and this counts as a sufficient engagement with the practice. When I interviewed my mother about small daily ways one could integrate pranayama into their life, I expected a philosophical answer about how you can’t just employ one spoke of the wheel — it’s useless without all eight.

But her answer surprised me — she sees pranayama as an independent practice with the ultimate goal of bringing your mind and body closer and dissipating the pressures of the outside world, if only for a moment.

“A mindful walk,” she says, is a way to practice pranayama. Focusing on your breath and the movement of your limbs as you walk is an act of conscious living. When it comes to tackling stress, going on walks is an oft-prescribed solution. Blasting music as you walk is a distraction, and you come back physically tired enough that your wired body relaxes.

Using a walk as a means to pranayama is different with regard to what you’re concentrating on. Pranayama dictates that you concentrate on the action of walking itself and how your body and breath accomplishes it. It brings your thoughts closer to your body in order for you to systematically unwind the stress from your limbs.

But Asha’s main point isn’t that pranayama can only exist in a mindful walk — “every act can be made mindful, like cooking, eating or driving.” The closeness between pranayama and mindfulness makes it an act that anyone can do for any length of time. It’s about bringing “your awareness back to the present.” The world, and our minds, are always moving at a million miles an hour, and the goal of pranayama is to slow that process down internally.

It is similar to every other practice in that if it isn’t done consistently, it loses its power. But its built-in mutability makes it easy to incorporate into our daily routines. For college students like us, Asha suggests taking the two minutes between walking into a classroom and the lecture to bring attention to your body and breath.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-cloiqjDR8/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

It’s not about falling into a deep, meditative stupor; it’s about choosing to concentrate, for a moment, on something small, automatic and vital. In this way, it’s a grounding exercise — not something that kills anxiety, but something that helps manage it. And it’s all in your head.