During my sophomore year of high school, I took a trip to New York City with my school’s orchestra. While there, we saw a performance at Lincoln Center. The experience was incredible, and it was some of the most beautiful music I’ve ever heard. My friends and I talked about the concert all night, commenting on the unique techniques the musicians used and the moments that gave us goosebumps. But when I mentioned how I loved the flash of light when the violin soloist twisted together the green and purple melodies, the room suddenly went quiet.

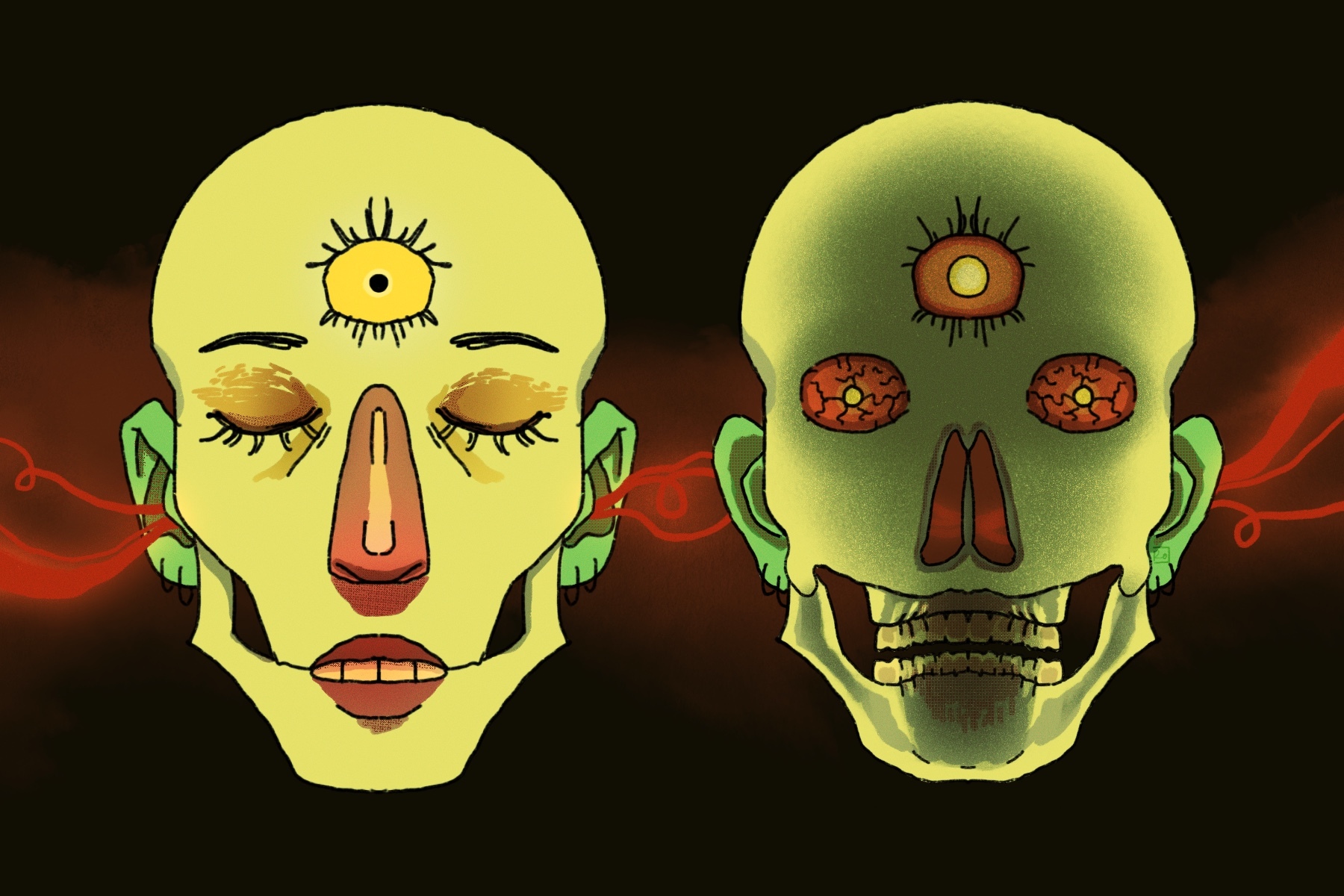

Everyone looked at me like I had spontaneously sprouted a second head. They had no clue what I was talking about. It didn’t take long to figure out that my experience at the show was completely different than everyone else’s. No one else saw the music. No one else felt a tingling sensation in their feet when the snare drum came in or tasted lemon juice during the trumpet solo. But as confused as my friends were about what I’d told them, I was even more baffled that my sensory experience simply didn’t exist to them.

That was the first time in my life that I realized my brain works differently than those around me. Everything I told my friends was completely normal to me; for as long as I can remember, I’ve had those kinds of responses while listening to music. It wasn’t until a few years later during an introductory psychology lecture that I learned the name for what I experience: synesthesia.

Synesthesia is a neurological condition that affects sensory responses. Instead of experiencing each sense individually, people with synesthesia experience multiple senses when only one of the senses is stimulated. The most common example of synesthesia is people who “see” music — they experience an involuntary sensory reaction that makes them associate a certain color or image with a certain sound. Synesthesia can happen with any of the senses. In my case, it happens with all of them. The number of people who have synesthesia is unknown, but it’s estimated that between 1% and 25% of the population experience some form of it. The wide range is attributed to the difficulty of identifying the condition. Several people, like myself, may live their entire life without knowing that their experiences are different; they’ve just never seen the world any other way.

Not much is known about synesthesia due to a lack of research on the subject. For years, it was difficult to conduct research about the condition, since many people didn’t believe it was real. However, the advancement of technology used in neurological study has prompted experts to take an interest in the condition in recent years. Dr. Richard Cytowic, a leading neurologist in the field of synesthesia study, began conducting research to validate the condition within the scientific community. Dr. Cytowic describes synesthesia as “an issue of cross talk,” or a result of increased neural connectivity. “All brains have cross talk among not only the senses, but among the different aspects of cognition and thinking. It’s just that synesthetes have more of this cross talk, and they’re consciously aware that they have it; therefore, they experience this overt synesthesia.”

While most people who experience synesthesia are born with it, there are a few cases of people developing synesthesia as a result of brain trauma. As the brain recovers from an injury, it will sometimes rewire itself with new connections. The new connections create new associations, therefore allowing a person who previously never had synesthesia to experience it for the first time.

Although most synesthetes experience the condition naturally, it is possible to train your brain to make new associations. Berit Brogaard, a professor of philosophy and psychology at the University of Miami, describes the relatively simple process of developing synesthesia as learning to create associations: “You pick a category and you start associating things in that category, which could be sound, and things in the other category, which could be colors. So once you start associating those things, you’re building new pathways.”

Plus, once you start training your brain to make these new connections, it will come more naturally. According to Brogaard, “Sometimes when people develop these synesthetic connections, for instance between sound and color, they can sometimes develop connections in other areas that have nothing to do with sound and color. The brain almost automatically starts associating other things with colors as well because it’s used to making those associations.”

Whether you’re born with synesthesia or you develop it later in life, synesthesia can improve cognitive function. For example, people with synesthesia often have exceptional memory. As Dr. Cytowic explains, “Synesthetes have measurably superior memories than the rest of us because, again, they have all these different sensations that help them hook things onto. Their ability to index their spatial memory is extremely good. They can see things in their mind’s eye.” In addition to retaining knowledge, some experts believe that synesthesia helps people learn concepts faster and more easily.

The condition is also associated with higher levels of creativity. In fact, many famous musicians including Lorde, Billie Eilish and Kanye West have synesthesia. Frank Ocean, another famous synesthete, actually created his 2012 album, “Channel Orange,” around his synesthesia. Another interesting case is Stevie Wonder, who experiences color-sound synesthesia despite having lost his sight at a young age. Many artists credit their synesthesia as the reason why they create music.

Although synesthesia is technically classified as a neurological condition, the people who have it consider it a special gift. Personally, I love the way my brain works, and I wouldn’t trade it for the world.

So much valuable content! Presenting views from various angles with clear logic. The blogger clearly has in-depth knowledge of the field. @bloodmoney