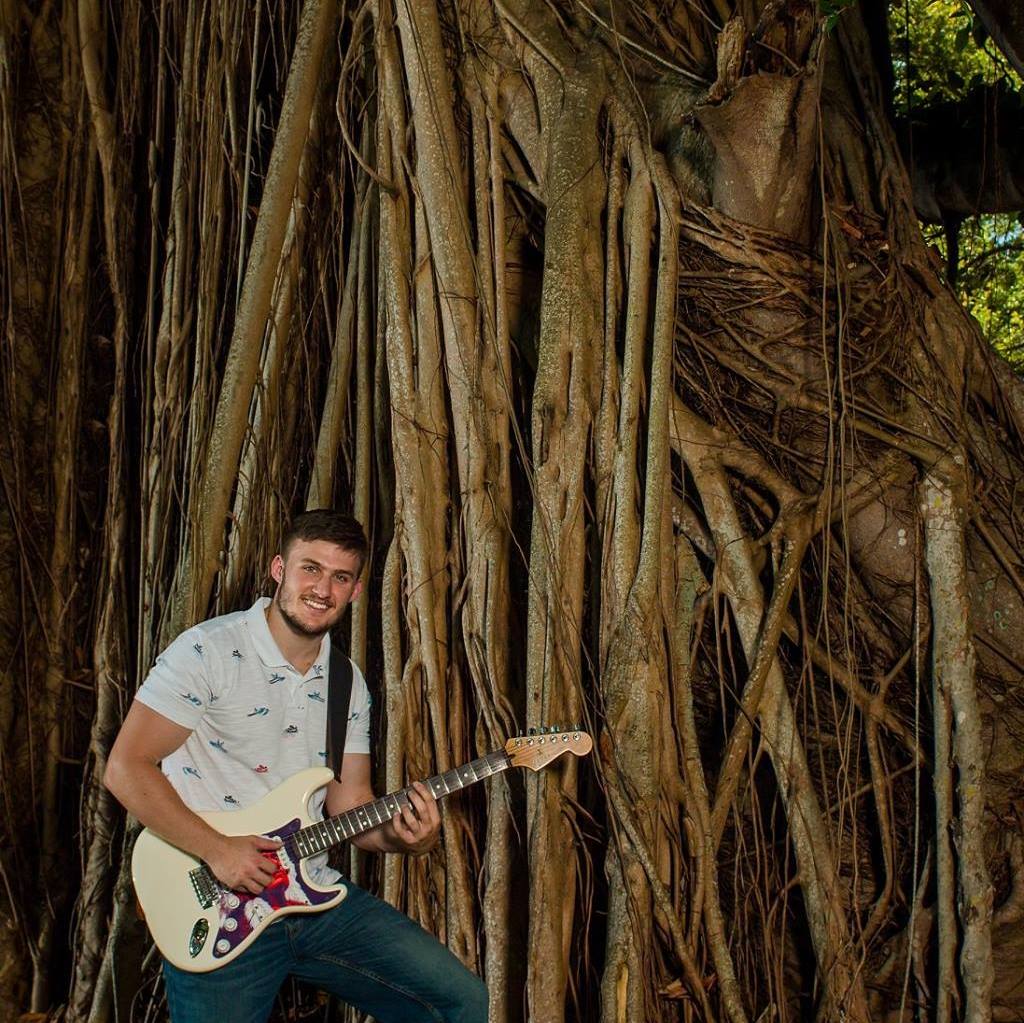

Music Man George Pennington

With his iPad band ‘Touch,’ the Music Education major is providing access to quality music and helping special-needs youth.

By Timothy K. DesJarlais, University of Arizona

A junior studying Music Education at the University of South Florida (USF), George Pennington is looking beyond traditional methods for new ways of teaching and learning music.

In addition to being nominated for the Harry S. Truman Scholarship and the Rhodes Scholarship, Pennington is a member of “Touch,” a non-traditional iPad band in which players use iPads instead of classical instruments to simulate musical sounds.

Looking to the future, Pennington shared his thoughts on music education and the importance of non-traditional music education in reaching a larger audience, styling himself as a “musical missionary.”

Timothy DesJarlais: What were the origins of “Touch,” and how did you get involved?

George Pennington: Originally, the genesis of the group was six or so years ago with two of my professors, Dr. Clint Randles and Dr. David Williams of the USF School of Music. They started the group to demonstrate the power of using different technologies, such as the iPad, as a way of supplementing technology into the music education classroom.

They started with the iPad, and, as it developed, they tried new things. Different graduate students started to work their way into the group as well. A couple of years ago, I was invited to do a jam session with some Ph.D. students around the school of music, and from there, they had a spot to fill in “Touch.” After seeing me jam, as well as talking and working with some of the band members, Dr. Williams asked me to join.

TD: How is your experience in “Touch” different from other traditional music education ensembles?

GP: This ensemble works in the sense that we create songs and perform by sitting together, working on a particular song and suggesting ideas in a syncretic, roundtable-discussion format. This is really fun and different since it is not the way most music education classes work.

TD: How do iPads replace traditional instruments in “Touch”?

GP: We use a couple different apps, and it’s kind of unlimited. The main one we use is GarageBand, which some will associate with multitrack and home recording. But, in that app, there are digital instruments you can use on the iPad, like simulated guitar sounds.

For instance, one person will be on the digital guitar while another will use the drum set option. Then, we also have some apps that are really kind of out-there and weird. We use wacky sounds as well as traditional musical sounds, and we mix it up as much as we can to show how versatile it is.

TD: The techniques in “Touch” are unique, but why are such untraditional methods a good choice for improving music education?

GP: It is multi-faceted. The iPad is cost effective, so it can be used in replacement of traditional instruments, which are very expensive. If you are looking at an orchestra, and you look at the percussion section, it will have the timpani, bass drum, marimba, etc. All of those instruments are expensive, and most schools can’t afford them.

But, if you take a few iPads, you can simulate those sounds and save money, which is especially important for a school that would either have to cut the music program or allocate those funds to something else.

You can achieve a really great sound with little money. That’s one reason “Touch” exists, to show how technology can be used in a traditional way. It also shows how music can be created, changed and manipulated in different ways, so it’s not always about the conductor on the podium. Instead, it can be a kind of conversation between all of the members of the ensemble about what works best and what doesn’t.

It shows how to be creative with music, no matter what medium you are using, whether it be a violin, a simulated violin or a guitar. Another reason “Touch” came about was for its use with special needs children. For instance, students with physical disabilities may not have any way to hold a violin or the sufficient motor skills for technical instruments, but they can still make music.

We like to tell the story of a girl who was an excellent player, but after she got into a car accident, she couldn’t play the flute anymore because she had lost mobility in her right arm. But, she could still use her left arm to play the iPad and simulate flute sounds.

TD: How accepting has the music education and fine arts community been of these new techniques?

GP: There has been a fairly significant amount of pushback, especially in the early stages of the iPad band. From my two years with the group, the attitude of the students who are embedded into the traditional ways of making music have yet to see the inherent value in using different technology in the music-making process, or they feel it may question their beliefs or force them to adapt and change.

There’s always a little pushback, and typically, the change among the most intertwined and studied have the most issue with it. So yes, there has been pushback, but there’s also a feeling from the general public that this seems like a common-sense improvement, especially if it saves money.

TD: Besides “Touch,” what other music education projects are you involved in?

GP: Some projects I have been doing around town include running an open-forum class every week, where I’ll offer a different course, like the history of opera, the history of hip-hop, music theory or music composition. I’ve had all sorts of topics that you wouldn’t be able to experience unless you were able to enroll in a music course offered at your local community college.

Most professionals in the workforce that may be interested in music, or are even pretty solid players, can’t do that. What I have been trying to do is turn those topics into weekly single sessions in public and assessable locations. I’ve been trying to bring this information and these new ideas to people, rather than having interested people forced to seek us out, kind of like a “musical missionary” of a sort.

TD: Where did your passion for music begin?

GP: It’s always hard to tell where it comes from. There are pictures of me as a baby standing up on a table with a little recorder, so maybe there was a natural inclination to music and a natural love for it.

But, the real lightbulb moment where I was like “This is what I have to be doing right now” is when my friend got a guitar for his birthday when I was eleven years old. He let me play every once in a while, and I was so obsessed with playing my friend’s guitar that the first thing I did was ask for one for my birthday.

Once I had the guitar, I was obsessed. I wanted to play everything, with different kinds of music, and it wasn’t long before I was forming bands with friends. From then, it has kept growing and evolved into a greater depth of musical appreciation.

TD: What bands do you currently perform in?

GP: I am in this band called “Troy Youngblood and the Soulfish” and a group called “Synergy in a Cup,” which is mostly hip-hop and funk with high energy stuff. I also play in a band called the “Flow Sisters,” which is more of funky jam group. Lastly, I have the “George Pennington Band” which is a project that pops up when I have a gig that calls for a bigger event.

TD: What are your future career plans?

GP: I think the way of going through K-12 and working day in and day out, tied into one school, is changing. There are teachers that are teaching modern band, which basically means rock-and-roll music. There’s also a lot of teachers that are traveling teachers or “teachers on carts,” who will bring their gear around to various schools.

Instructing educators how to teach is something I am interested in, so I hope this becomes a full-time, viable job rather than a specialized job. I am interested in the idea of an Arts Administration degree, which allows you to administrate how music is approached in a community. I’m not 100 percent sure, as I am early in my career process, but if I had to say, it would be administrating and working large-scale efforts.