On Feb. 9, the 2018 Winter Olympics will commence in PyeongChang, South Korea. To the backdrop of dancers, bright lights and wild cheering, athletes will march proudly into the Olympic Stadium behind their country’s flag. This year’s ceremony will once again feature Pita Taufatofua, the Tongan flag bearer who had the internet buzzing as he walked shirtless and oiled up into the stadium of the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio.

Since their genesis in 1896, the Games have existed as an arena for athletes to showcase their talents that have accrued over years of grueling practice. They are, as founder Pierre de Coubertin once said, a space for the “glorification of the individual champion.” And yet, this arena can do much more than glorify an individual.

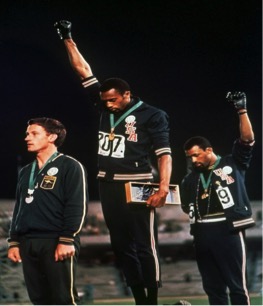

Behind the waving flags, the powdered slopes and the precious medals, the Olympics have often served as a way for athletes and organizers to voice their support for social and political change. In 1968, two African American athletes stood on the podium and raised a black-gloved hand for the entirety of the Star-Spangled Banner, a move which became known as the “Black Power salute.”

In 1980, the United States led a boycott of over 60 nations against the Moscow Games in protest over Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan. To see the greatest political struggles of a certain year, one only needs to look at that year’s Olympic Games.

2018’s Winter Olympics are no exception. In the 21st century, the Olympics have become a platform upon which the athletic community confronts rape culture, athletes take a stand on LGBTQ rights and countries negotiate political power.

#MeToo Impacts the Athletic Community

Just as Hollywood and the media industry are dealing with countless sexual misconduct scandals, so is the athletic community. At the forefront of the conversation is former USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University doctor Larry Nassar.

Just recently, Dr. Nassar was sentenced to 40 to 175 years in prison for using his position to assault young women in his care. Over 150 women came forward during the seven-day trial to share their traumatic experiences.

In the wake of the trial, the world looked to the United States Olympics Committee (USOC) and USA Gymnastics to take responsibility. At the behest of the USOC, and in response to what the Washington Post called “rising national outrage,” the entire USA Gymnastics board of directors was forced to resign.

Days after the trial, CEO of the USOC, Scott Blackmun, wrote an open letter apologizing to the athletes involved. “We are sorry that you weren’t afforded a safe opportunity to pursue your sports dreams,” Blackmun says in his letter. He goes on to say that the committee is working to change the culture of the sport, and to support athletes who were victimized by Nassar and others like him.

However, as celebrated gymnast and victim Aly Raisman pointed out, anyone can say they’re sorry. “It’s easy to put out statements talking about how athlete care is the highest priority.” Raisman says, “But they’ve been saying that for years, and all the while, this nightmare was happening.”

Raisman’s words and Blackmun’s actions reflect part of the seismic cultural shift that the country is currently undergoing. Talk is cheap when coming from organizations that have turned a blind eye to sexual misconduct for years. In order to survive the pivotal shift in what has become acceptable, institutions are realizing that they must make changes at a foundational level, and athletes have become fierce advocates for such a change.

Athletes Support the LGBT Community

It is not only our sexual culture that Olympic athletes are addressing, but also sexual orientation itself. Four years ago, when Russia hosted the Games in Sochi, there was controversy over the recent passage of a law that banned “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships” among minors.

President Putin sought to reassure gay athletes by saying that the law didn’t ban “nontraditional sexual relations,” only the propaganda of such. Predictably, his reassurances were hardly convincing

LGBT athletes used the heightened media attention of the opening ceremony and the events at large to voice their disagreement with Russia’s treatment of LGBT people. Finnish swimmer Ari-Pekka Liukkonen came out as openly gay days before the Games were set to begin, stating that he wanted to “start a broader discussion in connection with Sochi, because it’s sad that the legislation in Russia restricts the human rights of young people and others.”

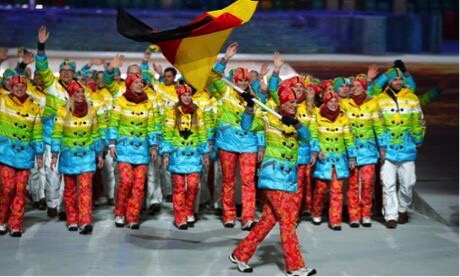

In addition to athletes like Liukonnen, entire delegations from various countries who used the Olympics to show support for the LGBT community. The German team marched in rainbow outfits while the Greek delegation wore gloves with rainbow tips.

These not-so-subtle protests helped pressure the International Olympic Committee into writing an anti-discrimination clause into its host city contract. The new rule forbids discrimination on the grounds of race, religion, politics and gender, deeming it “incompatible with belonging to the Olympic movement.” Such a move highlights athletes’ ability to promote change on an institutional level.

From the Ice Rink to the Negotiating Table

Aside from being a battleground for social issues, the Games also have served as a conduit for political negotiations. Amidst rising tensions between the United States and North Korea over nuclear programs and trade sanctions, North and South Korea struck up negotiations in early January in the hopes of easing long standing military tensions.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in optimistically framed the talks as a “precious chance to open the door” to further discussion. Meanwhile, U.S. officials are concerned that North Korea is trying to drive a wedge between the U.S. and South Korea while continuing to build a nuclear program.

Not only will the two countries march behind a unified Korean flag at the opening ceremony, they will also compete with a joint women’s ice hockey team, a move which the New York Times called the “most dramatic gesture of reconciliation” in a decade.

However, such progress is tentative and controversial on both sides. North Korea recently decided to cancel a joint cultural performance with the South, showing that the gap between the two Koreas is not closing as fast as some had hoped it would.

Meanwhile, thousands of South Koreans protested North Korea’s involvement and the use of the unified Korean flag. In a recent Reuters article, 24-year-old Kim Joo-hee from South Korea voiced his disgust with the South Korean government for allowing North Korea to march with them. “North Korea was all about firing missiles last year, but suddenly they want to come to the South for the Olympics?”Joo-hee asks. “Who gets to decide that?”

What’s the New Olympic Scorecard?

In a way, the politics of the Olympics showcase how history repeats itself. Women battling for the right to participate in the Games in the early 1900s leads to women seeking respectful treatment via Title IX now. Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 caused more than 60 countries to boycott the Moscow Games. The same solidarity between countries in the Moscow boycott also shows itself in this year’s Winter Games, as North Korea and South Korea try to mend relations.

So what’s changed? One possible answer is the people involved. It’s been shown, time and time again, that millennials tend to be more confident in their voices and more willing to implement social change than past generations.

The role of the athlete, inherently a youthful cohort, has become stronger. In the coming weeks and months, the world may very well be applauding their voices, not just their athletic prowess, as they advocate for a brighter future.