Writing can be such a fickle, fickle friend. When going well, your fingers can barely keep up with the pace of intriguing thoughts spilling from your mind. But when your mind has no thoughts to spill, the opposite ensues; the dreaded writer’s block. This can be an awful experience, but before you fall into a pit of despair at the thought of struggling with the same old issue until the end of time, there are three informative books about writing that you should get your hands on.

These three books tackle different issues that a writer may face without sounding like a dry, instructional manual. From drug addiction to the internal struggle over the Oxford comma, these three texts address just about any issue both the aspiring and seasoned writer may face.

1. “Bird by Bird”

Anne Lamott’s writing manual differs a bit from the traditional writer’s guide because she, through a brief overview of her life, explains how writing became such an integral part of her own identity. An element that Lamott stresses is for writers to always search for the truth in their own writing, and one way to practice this is by writing about your own life. Personally, I seriously dislike writing about myself but to become better at the craft, it’s probably something I should spend more time doing.

Lamott uses anecdotal phrases that she learned from her father, who was an influential player in her writing career. She explains that writing should be done “bird by bird,” which means writers should focus on the small steps taken during the writing process rather than the finished product. A lot of writers have a general idea of what they want their finalized piece to look and sound like but Lamott advises that writers should be open to the “twists and turns” that might crop up during the crafting.

“Bird by Bird” is a useful tool for the writer who struggles to find the right emotional balance in their pieces. Lamott claims that writers are usually the ones who observe the world rather than actively participate, which is why it’s so important for writers to be able to convey what they see and feel for their readers. This writing guru’s book successfully engages the reader because it has a conversational, comfortable voice that offers guidance without feeling authoritative.

2. “How to Write Short: Word Craft for Fast Times”

Roy Peter Clark, a writing teacher and journalist, created the perfect manual for the writer who struggles with short forms of the craft. In his book, which is less than three hundred pages, Clark explains in equal measures the “how” and the “why” of short-form writing. In the first half of the book, the wordsmith covers the key idea that just because writing is short, doesn’t mean the attempt to do it well should go out the window. He explains that short writing can still move mountains and he cites different documents that have helped shape history, even with their small word counts: “The Hippocratic oath, The Twenty-Third Psalm, The Lord’s Prayer, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, The Preamble to the Constitution, The Gettysburg Address, the last paragraph of Dr. King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech…If you add up the words in these document, the sum will be fewer than a thousand, 996 by my count.” Our very own history has been formed and reformed by the ability to say what you need in as few words as possible, so it’s important that all of us be able to do it well.

Clark’s book is a necessary item for writers who find themselves in a constant battle with maximum word counts. At the end of each chapter, Clark provides two to three different exercises that can be practiced daily to really hone in on the heart of short-form writing. He suggests keeping a daybook and jotting down all forms of short writing that you might encounter throughout the day—these range from bumper stickers, tweets, billboards and more.

One element of Clark’s book that I benefitted from was the suggestion of analyzing the words a writer chooses while writing. That seems like a very obvious suggestion, but let’s use the former sentence to really practice what Clark is preaching: I used the word ‘benefitted’ to explain what I learned from the text; what if I just used the word “learned” instead? The former “benefitted” is ten letters, versus its shorter seven-letter comrade. You might be sitting here, thinking: “why in the world would three letters make a difference?” Consider the world we live in, where platforms such as Twitter restrict our character count to a measly 280, forcing its users to be concise when trying to tweet out their thoughts and ideas, regardless of how inane they may be (I’m looking at you, Mr. President.)

Something I, and I assume many other writers, struggle with is cutting the fluff from writing. You say “cut out the unnecessary parts.” “But ALL of it is necessary” I whine. I mean, if it wasn’t important, I never would have written it in the first place! Clark helped me realize that I was: (A.) wrong and (B.) approaching the concept of editing incorrectly. He lists some easy elements to remove (or avoid in the first place) from a piece during the editing phase: “Adverbs, adjectives, strings of prepositional phrases, intensifiers, qualifiers, jargon and Latinate flab.” The editing process can be hard because a writer is forced to walk the very thin line of trimming unnecessary words while still preserving the heart of the piece. Clark’s handy instructional text stresses that the original message and voice of the writer should still be present after undergoing major editing. Clark sums up his point with clever imagery: “First prune the big limbs, then shake out the dead leaves.”

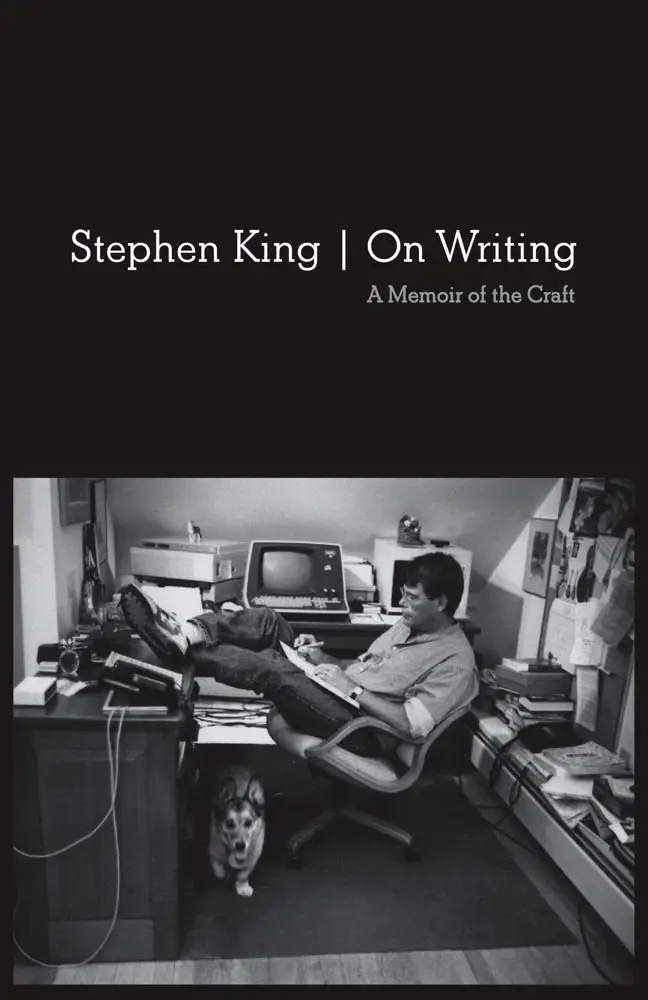

3. “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft”

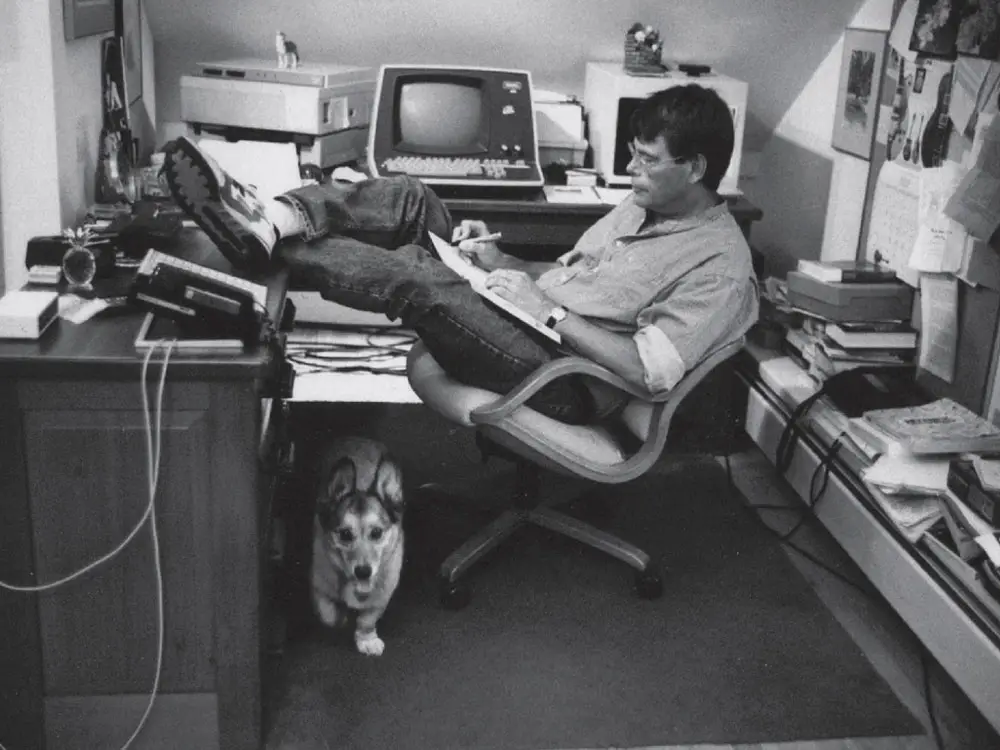

Of course, I’m going to include a writing text by Stephen King because, in my humble opinion, the man could do no wrong. In the memoir, King talks about his own trials and tribulations as a novelist and it’s reassuring to know that even a critically acclaimed writer struggled to get his career off the ground.

The prolific horror mastermind divides his instructional piece into five sections: “C.V.” in which King talks about the events that shaped his writing career, “What is Writing” in which the horror maestro urges readers to take writing seriously, “Toolbox” where King discusses the working parts of the English language, “On Writing” when the mastermind offers advice to aspiring readers and “On living: A postscript” where King finally addresses his brush with death in a hit and run and how it affected his life. Throughout each section, the horror expert-turned-writing instructor emphasizes his cardinal adage: writing well is important, so here’s how to do just that.

King openly discusses his battles with drugs and alcohol in his memoir and that reflects his own ideology about writing. He believes that one of the most important responsibilities of a writer is to present all the facts of a story, in as few words as possible. King also makes a point to address the notion that musicians and artists need drugs to fuel their creative prowess: “Substance abusing writers are just substance abusers—common garden-variety drunks and druggies, in other words. Any claims that the drugs and alcohol are necessary to dull a finer sensibility are just the usual self-serving bullshit.” Kudos to you, Mr. King, for being in the minority of creative people who address this fallacy. If the mastermind behind cult classics such as “The Shining”, “Carrie” and “The Stand” can produce hair-raising horror stories without mind-altering substances, I think the rest of the creative world can aspire to the same.

A topic that King hones in on is a writer’s vocabulary and why it should take priority in the hierarchy of writing tools. The horror maestro explains that while vocabulary is an indispensable tool, there shouldn’t be any forceful effort to improve it. As someone who has been reading and writing since I discovered I could, that thought process seems pretty ass-backward; why wouldn’t I be making a concentrated effort to sound smarter? King, with the use of comical similes, explains why flexing one’s vocabulary is glaringly obvious and slightly embarrassing: “One of the really bad things you can do to your writing is to dress up the vocabulary, looking for long words because you’re maybe a little bit ashamed of your short ones. This is like dressing up a household pet in evening clothes. The pet is embarrassed and the person who committed this act of premeditated cuteness should be even more embarrassed.” That’s not to say that longer, “more advanced words” don’t have a place in the literary world but if we were to water down King’s basic point, it would be that the first word that comes to mind while writing is typically the one that fits best, and trading it in for a higher-level synonym doesn’t necessarily mean the sentence is going to sound better. In layman’s terms, go with your gut.