The cold fact is that every college is essentially a business whose service is to provide an education, or rather to supply degrees, for a high price in a notoriously competitive market. This fact is why colleges are increasingly tending towards a more capitalist attitude when dealing with finances, hence the upsizing in facilities, the waning in faculty salaries and the swelling of student costs. Even with governmental help, colleges have no obligation to provide resources, like those in mental health care, that don’t contribute in some way to this degree-for-fee business.

Yet many, if not most, American colleges offer mental health services, which actually isn’t legally required, in a keen response to the rising rates of depression among students. Though it’s true that the supply of professionals is too scant to properly meet the growing, and now burdening, demands of students seeking help, the blame for this supply-demand gap is often wrongfully placed on colleges as institutions, as if they are the ones responsible for causing, and thus treating, the various mental problems that trouble their students.

However, many of such problems are environmental. When students transition out of high school, they are instantly confronted with impending adulthood. But those students who had been too sheltered, by no fault of their own, in their pre-college years, are usually too callow to deal with the intense stressors associated with this real, yet unfamiliar, adult world. Adaptation is a learned skill that takes experience in failure and resilience, and many college students simply haven’t had the chance to develop that skill and are immediately thrown into an autonomous role that mandates future planning, nearly finite decisions and clear-cut execution. Thus, from this unprepared college introduction erupts, unsurprisingly, one of life’s most universal watersheds—the “quarter-life crisis.”

The “quarter-life crisis,” in varying degrees, usually well disguises itself with symptoms congruent with mental illness, namely depression and anxiety. Inhibited motivation and interest, hopelessness, suicidal thoughts and sometimes incapacitating angst and other symptoms, are a natural occurrence among young adults who are in search for their life’s calling. But such crisis is indiscriminate of student status; it is beyond college jurisdiction, and those affected would’ve likely had their career-related depression and anxiety regardless of whether they were in school or not.

Many articles, like ones from “Newsweek” and the “Washington Post,” make anecdotal cases that a student’s mental suffering while in college is primarily caused by college. Clearly, this is an inappropriate correlation. To blame college for causing certain mental illnesses is to ignore the societal considerations that colleges have no control over, which isn’t only immature, but also ignorant.

Yet, the true fault doesn’t just lie in immaturity or ignorance, but rather in the more dangerous quality that results when the two collide—self-entitlement. Even when colleges aren’t legally required to provide mental health services, they still do, especially with the help of governmental funding for programs like suicide prevention. Yet, students, even as featured in the “New York Times,” seem unappreciative of not only their colleges for the treatment provided, but also the professionals for offering a quality of service that students believe is undeserving. These students complain about long waits and involuntary hospital admissions, while simultaneously criticizing schools for under-marketing their services and not taking action when a student ends up committing a tragic act, suicidal or not.

In the past, when students committed suicide on campus, they were usually accountable for their actions, not the colleges. Only recently, most notably since the 2000 death of Elizabeth Shin who suicided by self-immolation at MIT, have movements begun to shift the blame for suicides onto schools, as if the students who committed the acts weren’t adults capable of making their own decisions. Most such movements are in the form of distraught parents who not only try to seek reparation for their loved ones’ deaths, but also surreptitiously try to put colleges back in loco parentis, which legal scholars consider as part of a bygone age.

As more college students become depressed and anxious due to school or career-related stresses, relationship problems or even continuing treatment from high school, they should remember that colleges are businesses that they choose to pay for certain services, and be thankful when their institutions are willing to provide mental health services even when not bound by legal contract.

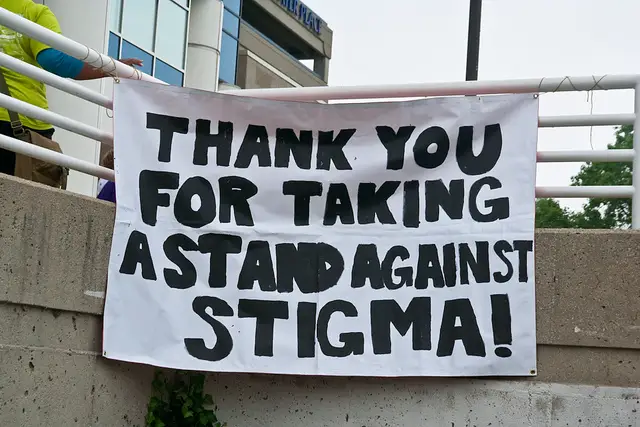

Colleges are not the enemies in the war against mental health stigma, but rather immaturity and ignorance. The real battle comes not from the fact that colleges aren’t good enough, but from the self-entitlement among students that colleges should be good enough. Counselors aren’t babysitters who made promises to parents to take care of students’ every need. Most importantly, colleges aren’t substitute parents.

[…] Source: Colleges Aren’t Parents, They’re Businesses […]