When viewers tuned in to the season premiere of “South Park” for their 20th season this past September, no one was sure what to expect. Well, that’s not entirely true. Viewers knew that they could count on the show to satirize every facet of contemporary American culture within range.

For two decades, “South Park” has been the source of the sharpest and most incisive skewering of Americana on television (piss off, “Saturday Night Live”). 2016 has not been without its share of head-spinning topics: the (at the time) pending election, a dead gorilla at the Cincinnati zoo, Pokémon Go and a slew of dead celebrities all highlighted the year that’s been. It seemed that with so much on the table this year, creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone had ample fodder to draw from.

Yet something troubled me. As I reflected on the events of the year, it occurred to me that they were all ground that “South Park” had covered before.

The 2016 election boiled down to a choice between the lesser of two evils; certainly everybody remembers when “South Park” lamented the last time the American public was faced with two abysmal choices. If you don’t, then your older siblings (and maybe your parents) might recall when Parker and Stone first lampooned the Pokémon craze back in 1999. And while it may seem like the Angel of Death was specifically targeting actors and musicians this year, don’t make the mistake of believing that this sort of thing hasn’t happened before.

It seemed any topic of discussion in 2016 that might be angled into an episode of “South Park” has already been an episode of “South Park.” Police brutality? Check. Climate change? Check. Radical Islamic terrorism? Double check. Donald Trump? I think you get the idea.

The list goes on and on. “South Park,” it would seem, had exhausted every major conversation point going into this season. So where could they go from here?

Since the show debuted twenty years ago, “South Park” has always been purely episodic. Each episode can—and must—be viewed as a stand-alone story. Like every adult-toned animated series that existed at the time of its inception, “South Park’s” sole obligation was to give viewers a half-hour of goofy, ribald, non sequitur, carnivalesque insanity without asking them to think too much about what happened in the previous episode. This allowed Parker and Stone to pull stunts like killing Kenny every episode, only to have him return happy and unscathed the following week.

Sure, there was the season where Mr. Garrison was dismissed from teaching—leading to feuds with both his puppet, Mr. Hat, and his replacement, Ms. Choksondik. But even that arc was given a laissez-faire treatment and was resolved swiftly. (I have a sneaking suspicion that the character of Ms. Choksondik was just a ruse by Parker and Stone to get away with saying “chokes on dick” on national television.)

“South Park” has even included a handful of trilogies over the years, such as “ The Coon and Friends,” “Imaginationland” and “Black Friday.” Still, throughout its run, the approach has been the same: One story per week, ad infinitum.

Yet this approach saw itself morph in season eighteen, when it was discovered that Randy Marsh is in fact New Zealand singer Lorde. What started as an early throwaway joke became something of a crucial plot point as the season wore on, and the Randy-as-Lorde story arc developed to the point that the season finale hinged on the performance of Randy’s alter ego.

Last season, Parker and Stone took the concept of a recurring, season-long arc another step forward with the introduction of PC Principal. Each week saw the citizens of South Park endeavor to make their redneck mountain town more progressive by gentrifying the lower economic areas (Kenny’s house) and installing a Whole Foods. By season’s end, PC Principal and the rest of the cast found themselves in the midst of a conspiracy involving ads.

So naturally, the logical progression for “South Park” was to go balls out and completely serialize season 20. I remember watching episode one (“Member Berries”) and thinking to myself, Man, they’re introducing a lot of plot lines; how are they going to resolve this by the end of the episode? Of course the goal was not to resolve the episode’s branching stories but rather to set the stage for a season long saga.

But why do this? In “Member Berries,” the citizens of South Park call upon J.J. Abrams to rewrite “The Star-Spangled Banner.” One could argue that this is a nod to Abrams’ knack for producing drawn-out, convoluted serials. Many remember “Lost” as one of the first shows that forced viewers to come back week after week to uncover the mysteries the show posited, only to be confronted with even more questions and less answers.

Thus is the state of television today. I mentioned before that “South Park” was born of an era where show-runners needed only to produce one story per week. But the episodic format is a relic of yesteryear.

Today, serialized shows like “The Walking Dead,” “American Horror Story” and “Game of Thrones” thrive because they follow the template set forth by J.J. Abrams and “Lost.” Viewers demand lengthy, compelling stories that can’t be resolved in a single episode. They gravitate toward certain characters and story arcs that drag out over several weeks. And as the aforementioned shows have taught us, the longer they drag out, the better. Even sitcoms are under the spell.

In the commentary for season 19, Parker and Stone explain how the “political correctness” angle (and specifically PC Principal) of the season was the show’s way of evaluating its place in modern times. The American landscape has grown increasingly more PC over the last two decades, yet “South Park,” both as a show and as a fictional town, seems stuck in this 90s mindset that you can say anything you want without worrying about who you offend. Season 19 was a way for the show to poke fun at itself, while simultaneously trying to craft a new identity.

It appears as though that was the aim of this season as well. By invoking the name of J.J. Abrams, Parker and Stone acknowledge that their show is a vestige of a bygone time and that it requires an overhaul. The episodic days are over; let the serialization begin.

Did it work for “South Park,” though? Was the serialization of season 20 a success? The problem with the modern TV series is that apart from the season premieres and finales, it’s difficult to remember what happened in any specific episode. For instance, I recall vividly the beginning and ending of the most recent season of “The Walking Dead,” but put a gun to my head and I still remember little of anything that happened in between. It was all either fallout from the premiere or buildup toward the finale.

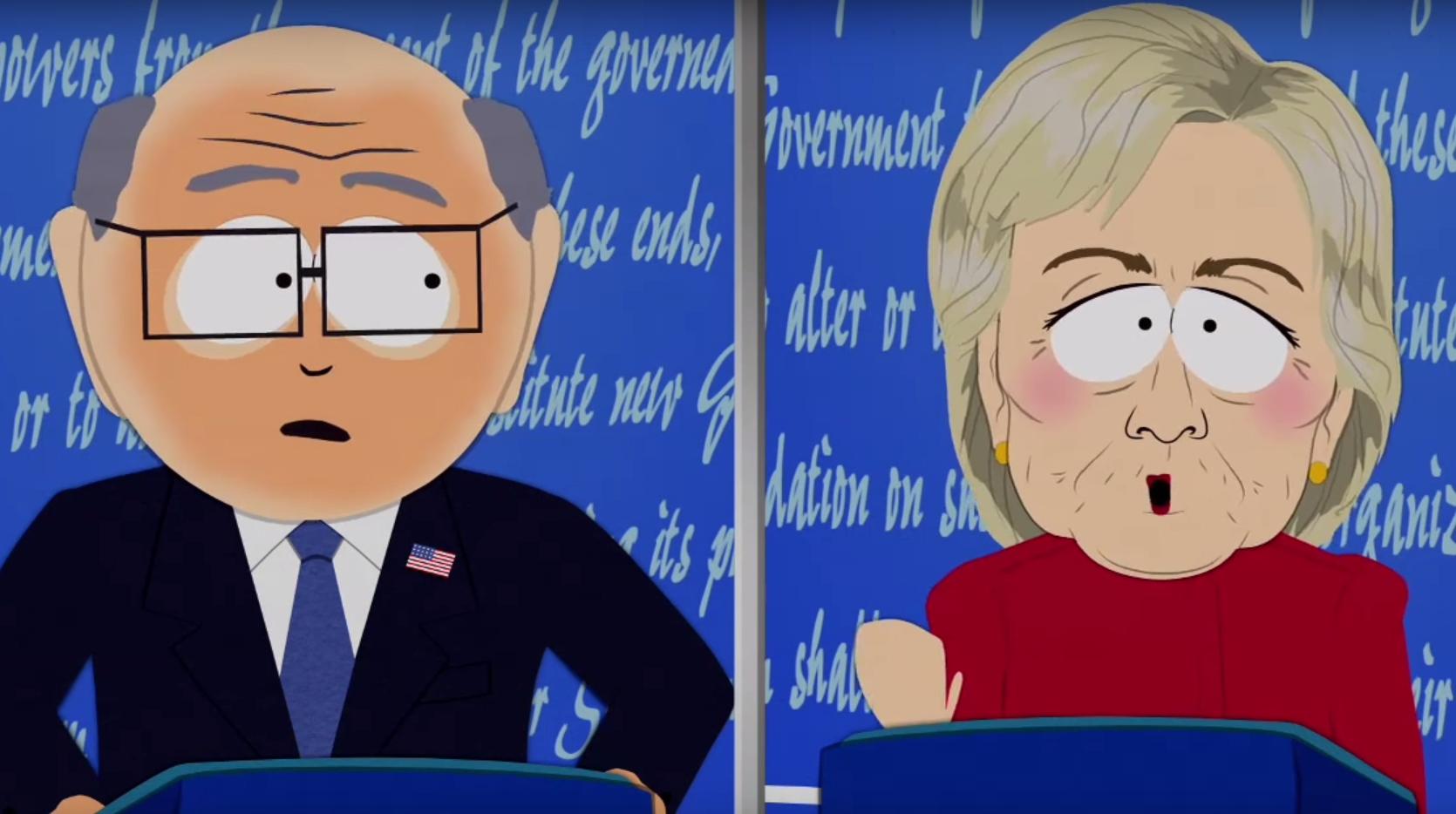

Such is the case with season 20 of “South Park.” I know that at some point Cartman severs ties with his old friends and gets a girlfriend; I know that Gerald Broflovski is tricked into turning himself over to the Danish government; I know that Mr. Garrison (as a facsimile for Donald Trump) gets elected President; I know that the Member Berries infiltrate the White House; I know that Bill Clinton and Bill Cosby together form a “Gentleman’s Club.” Don’t ask me to remember what respective episodes these events occurred in, though.

All this murkiness points to a general sense of discomfort Parker and Stone must have undoubtedly felt unspooling the season. What’s most disquieting is that twice this season, “South Park” did not air when it was scheduled.

If you weren’t aware, the show has a strict production cycle of six days; the writers begin scripting an episode on Thursday, and by the following Tuesday they have a finished animated product. It’s a grueling schedule, but despite their unforgiving deadline, Parker and Stone have never failed to deliver an episode to Comedy Central on time. Until this season, that is. No reason or official statement was given by Comedy Central as to why the episodes weren’t aired, but it informs speculation that the serialized structure of this season’s episodes was to account for the halt in production.

The title of the season finale,“The End of Serialization as We Know It,” appears to indicate a sense of weariness the creators developed with their own creation. It could mean that Parker and Stone are done with this format altogether. Who could blame them? The season was almost too much of a departure from what “South Park” is.

Gerald’s villainous turn as an internet troll is going to be a difficult image to shake. The show has taken us to dark places before, but seeing Kyle’s typically gentle, compassionate father gleefully troll a cancer patient will stick with viewers for a long time. Conversely, Cartman’s softening was also frustrating to see.

Part of what makes “South Park” such a riot is the assurance that no matter what the topic of the episode is, Cartman will always take the vile, contrarian viewpoint. That staple of the show was missing this season, for the whole season. And true to the nature of serialized TV shows like “Lost,” season 20 failed to bring resolution to the origin and purpose of the Member Berries (they were cute, but seriously, what they hell were they supposed to be?).

Though season 20 may have been a failure, it never failed to make me laugh. I can always count on “South Park” for that. And I did tune in every week, so I give them credit for consistently bringing me back. I also appreciate Parker and Stone’s willingness to experiment. They’ve always been fearless artists, daring to delve into musical theater and puppetry; can I honestly shame them for trying something out of their element? I can’t, and I won’t hear anyone else who tries to. But if you didn’t find yourself laughing this season, worry not. “South Park: The Fractured But Whole” hits store shelves this spring. Say that name out loud and tell me “South Park” isn’t funny anymore.

South Park isn’t funny anymore!!!

…I’m not kidding.