Molly Ringwald is an American actress well known for her roles in several ’80s films directed by John Hughes, such as “The Breakfast Club” and “Pretty in Pink.” Ringwald’s unique look and talent captivated Hughes and inspired films with roles designed just for her, which led many to refer to the young actress as Hughes’s “muse.”

While many feel her roles in the hit ’80s films to be iconic, Ringwald considered them to be important socially. She said that Hughes’s movies reflected teens in a realistic way that everyday young people could identify with. In the pre-Hughes era, this had been attempted in after-school television specials, but Ringwald insists that these attempts to connect to and represent teens failed because the music was “corny” and the script was obviously written by adults.

To many, Hughes’s films offered something different. The actress wrote in The New Yorker that Hughes’s movies “convey the anger and fear of isolation that adolescents feel and seeing that others might feel the same way is a balm for the trauma that teenagers experience.”

The famous director’s movies, such as “Sixteen Candles” and “The Breakfast Club,” unveiled the impact of the seemingly unimportant events of adolescence. By doing so, Hughes made the struggles and importance of younger generations known. “John wanted people to take teens seriously,” said Ringwald. And after his films, people did.

While she has seen firsthand how these teen-centered comedic works that jump-started her career have helped individuals, she admits her feelings toward them have shifted.

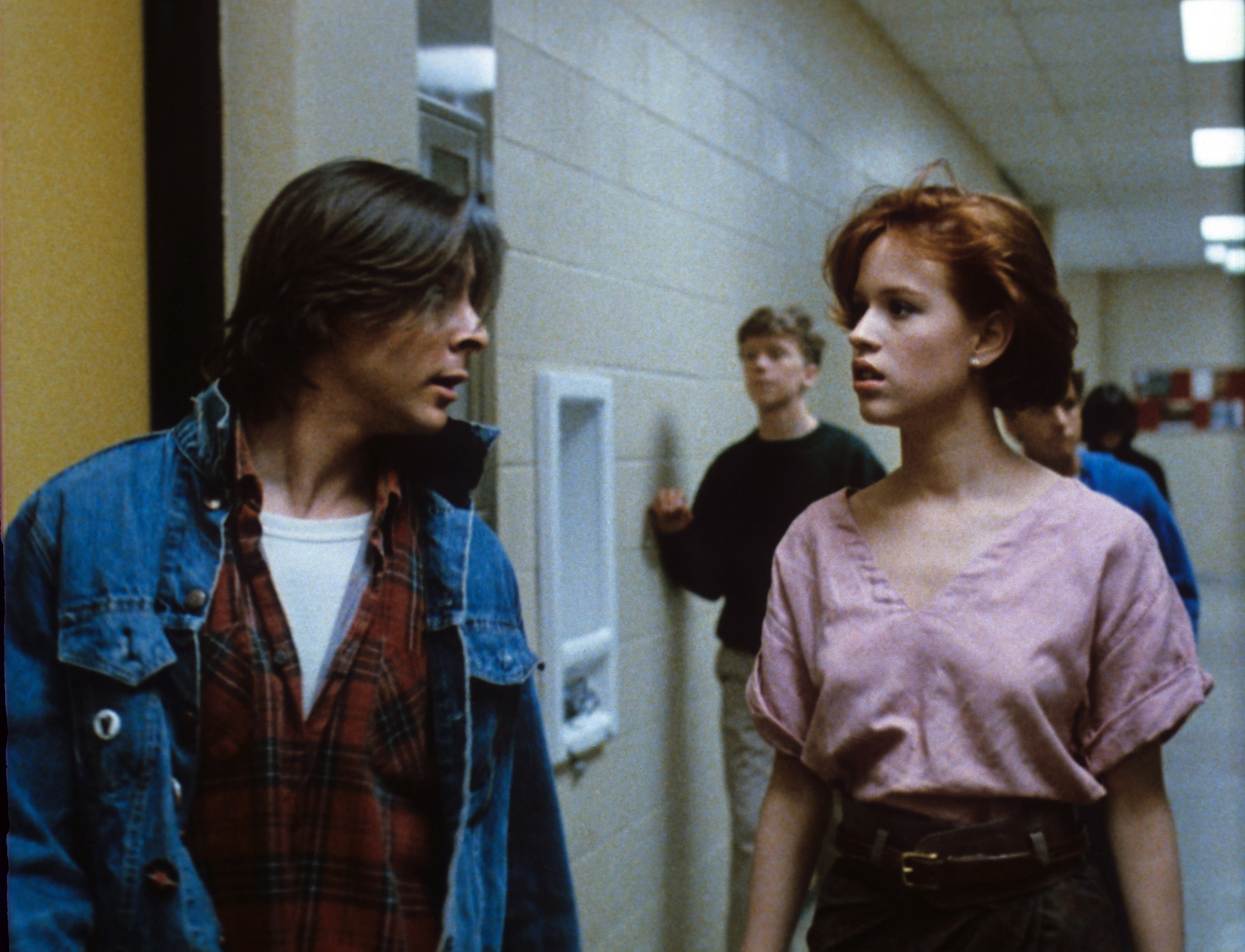

In her essay “What About ‘The Breakfast Club,’” Ringwald discusses how her journey of analyzing the Hughes movies with a modern outlook began when her 10-year-old daughter begged to watch “The Breakfast Club.” The redheaded star who played Claire in the film expressed her worries about her young daughter watching the film, especially given the sexually suggestive and drug scenes.

After a writer-director friend assured Ringwald that kids tend to filter out what they don’t understand, she allowed her daughter to watch “The Breakfast Club,” but only with her. Ringwald figured it would be better if she were there to answer the uncomfortable questions and could serve as an unconventional bonding moment.

The ’80s star found that her friend had been right, and that none of the sex stuff seemed to register with her daughter. However, Ringwald’s 10-year-old did gasp when she thought her mother had shown her underwear onscreen.

In the film, the bad-boy character, Bender, hides from a teacher under the table where Claire (Ringwald) is sitting. While there, Bender looks under Claire’s skirt and it is then implied, although not shown, that he touches her inappropriately. She was quick to point out to her daughter that the woman in the underwear wasn’t really her. However, Ringwald “felt the clarification inconsequential.”

Despite her intentions to provide context for the film, Ringwald didn’t elaborate to her daughter what had happened under the table. “She expressed no curiosity in anything sexual, so I decided to follow her lead, and discuss what seemed to resonate with her more. Maybe I just chickened out.”

Eventually, what Ringwald thought would be a learning experience for her daughter turned out to be an awakening for herself. She says in her New Yorker essay that she continued to think about that scene long after watching the film with her daughter. And she thought about it again this fall, after several women came forward with sexual-assault accusations against the producer Harvey Weinstein.

As the scandal unraveled and the #MeToo movement gathered support and ferocity, Ringwald continued to analyze the classic Hughes films that helped her become a star. She considered her role as a mother, both onscreen in television shows such as “Riverdale,” and in real life. Through raising kids, starring in teen films and now playing mother roles in teen television dramas, Ringwald felt she had a connection to the younger generation. She thought about what film portrayal meant for current issues and society’s ideas toward them.

In turn, the “Pretty in Pink” star said, “If attitudes toward female subjugation are systemic, and I believe that they are, it stands to reason that the art we consume, and sanction plays some part in reinforcing those same attitudes.”

Ringwald had been in three Hughes films. When they were released, they made enough cultural impact to get her featured on the cover of TIME magazine and for Hughes to be hailed as a genius.

Indeed, “Sixteen Candles,” “The Breakfast Club,” and “Pretty in Pink” regularly air on television today and are even taught in schools.

While Ringwald recognizes the positive components of the Hughes films, she became troubled by the attitudes they could have, and still might be, reinforcing. Haunted by the scene with Bender under the desk, she considered some of the other scenes that may have reflected sexual misconduct.

Throughout the “Breakfast Club,” Bender sexually harasses Claire. He sexualizes her numerous times and then takes out his rage on her calling her pathetic and mocking her as “Queenie.” He even demands that she talk about her own sexual experiences in front of the other students in the library. “Bender never apologizes for any of it,” said Ringwald in retrospect, “but nevertheless, he gets the girl in the end.”

In “Sixteen Candles,” a character called the Geek and Farmer Ted make a bet with friends that he can score with Samantha (Ringwald). By way of proof, he says that he will steal her underwear.

The film also has an instance of the popular boy, Jake, trading his drunk girlfriend to the Geek. When she wakes up in the morning he asks her if she “enjoyed it.” Caroline (Jake’s girlfriend) responds that she has a “weird feeling” that she did.

Looking back at the scene in light of the #MeToo movement, Ringwald found, “She had to have had a feeling about it, rather than a thought, because thoughts are things we have when we are conscious, and she wasn’t.”

Ringwald continues to say that if she sounds overly critical, it is only with hindsight. The beloved actress still believes the Hughes films offer something to struggling teens: representation and understanding.

However, considering the attempted and suggested comedy toward nonconsensual sex, as well as the undercurrents of sexual assault and harassment, Ringwald admits to struggling to understand how Hughes was able to write with so much sensitivity, and also have such a glaring blind spot.

In the essay, Ringwald admits that she hopes that Hughes films will still be viewed and taught in schools, in order to address the weight and struggle of being a teen. However, Ringwald feels that as society shifts, so should the conversations about the scenes portrayed.

As a result, she urges people who view the films and show it to others to take the time to discuss their flaws. What is wrong with what Bender does to Claire? Why is this unacceptable? What should Jake have done when Caroline became so intoxicated?

Ringwald says these sorts of conversations can allow the Hughes films to endure without reinforcing the negatives within them.