The 82nd Academy Awards, like every other Academy Awards, was a star-studded evening celebrating talent, glitz, and famous films released the previous year. Neil Patrick Harris performed a jazzy showtune to lull the crowd into a captivating atmosphere. Household names awarded shiny statuettes to blockbusters such as “Up,” “The Hurt Locker” and “Avatar.” While these films effectively monopolized the pocket money and attention of many moviegoers, an Australian stop-motion film about two pen-pals, “Mary and Max,” opened to a much smaller audience the same year.

A decade later, “Mary and Max” remains a fantastic film with an emotional payoff on par with “Up”‘s tragic first 10 minutes, and it sports a visual style just as unique — if not necessarily as grand — as “Avatar”‘s Pandora. While the film might have been overshadowed by these Hollywood colossuses at the time of its release, “Mary and Max” remains a heartfelt story that deserves a streaming-era Renaissance.

“Mary and Max” tells the story of two people whose shared identity as outcasts becomes the basis of a lifelong friendship. At the beginning of the film, Mary is an 8-year-old girl living in a suburb in Melbourne, Australia. She copes with an alcoholic mother and an absent father. Bullies torment Mary at school for a birthmark on her forehead shaded “the color of poo.” She plays with toys made of kitchen scraps, loves condensed milk and has no real friends.

Max (voiced by the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman) is an obese, Jewish, middle-aged atheist living alone in Manhattan. Max is erratic and obsessed with order; he struggles to read other people’s emotions and finds sarcasm bewildering. Many of these quirks are symptoms of his Asperger’s syndrome, which Max only discloses halfway through the film. He lives alone with several pets and no surviving family. Like Mary, Max also struggles to maintain lasting relationships.

A chance incident in the post office leads Mary to write Max a letter, sparking a back-and-forth correspondence that comes to define Mary’s childhood. The film follows Mary and Max’s relationship as Mary copes with grief, growing up and transitioning to adulthood. (Adult Mary is voiced by Toni Collette, known in our modern culture-verse for her terrifying performance in “Hereditary.”) Meanwhile, Max stumbles into a strange combination of misfortune, wealth and various odd jobs. The exchange of letters ebbs and flows between the two as their lives unfold in unpredictable — and often devastating — ways.

The story of Mary and Max’s friendship is also partially autobiographical. In interviews, director Adam Elliot discusses how “Mary and Max” is based on a pen-pal relationship from his own childhood. This tidbit of information provides the story with an element of real-life poignancy, and it perhaps explains Elliot’s meticulous attention to detail when coloring in the details of his sophisticated world.

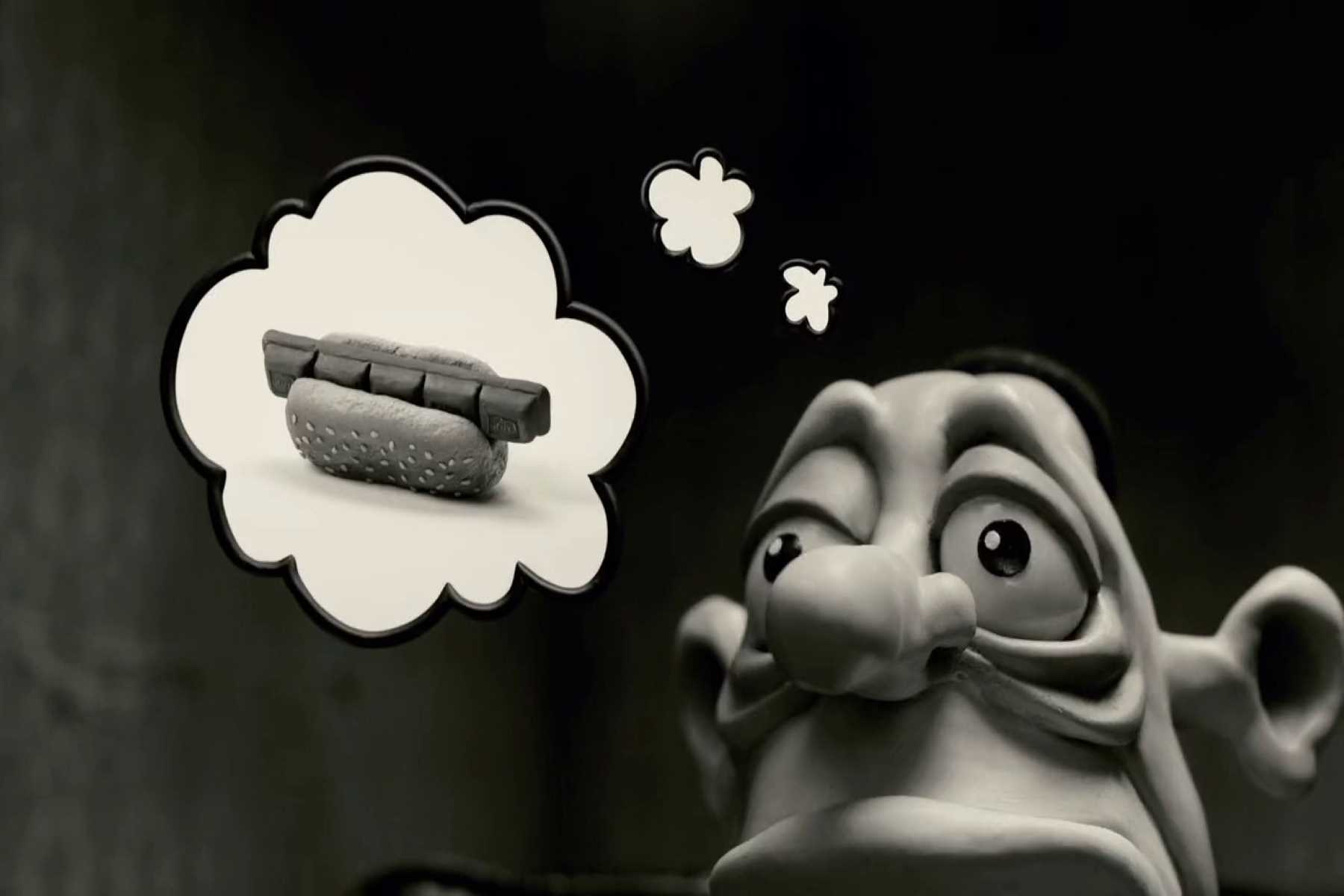

Elliot rounds his characters by imbuing them with unique traits and idiosyncrasies. For example, Max has a penchant for chocolate hot dogs: slabs of milk chocolate shoved between two hot dog buns. He sends the recipe to Mary in one of his first letters, and the concoction becomes a recurring symbol throughout the film to represent optimism and friendship. Elliot weaves many such quirks into his story, breathing life into its otherwise inanimate slabs of clay.

The film was produced using clay figures rendered mobile through stop motion animation. This style is usually called “claymation,” but Elliot prefers the portmanteau “clay-ography” because his stories are often also biographies. Creative names and descriptions aside, stop motion animation is grueling to execute, as it requires hours of precise movement with real-life miniatures.

More impressive is the fact that “Mary and Max” takes place in a monochromatic world. Mary’s suburbia is basked in sepia, whereas Max’s New York world is framed in black and white. Elliot balances out this darkness by introducing touches of red in certain frames, such as the paper clip Mary uses to keep her hair in place or the pom-pom she sends Max in one of her initial letters. These symbols splash color into an otherwise familiar setting, adding to the film’s artistic value.

The choice to drain the film of color no doubt complicated the stop-motion process, but it also highlights how “Mary and Max” is a story about people coping with tragedy. In turn, the choice to reintroduce color into certain scenes demonstrates how the two’s friendship gives Mary and Max’s lives hope in spite of their unfortunate circumstances.

This is perhaps best exemplified when Max attaches Mary’s pom-pom atop his yarmulke, a symbol of how her friendship has changed his worldview. Upon donning the pom-pom, their lives have become intertwined, and the visuals of subsequent scenes reflect this newfound relationship.

Another aspect that sets “Mary and Max” apart from most animated films is its ability to seamlessly switch between opposite tones. Like Elliot’s previous short film, “Harvie Krumpet,” “Mary and Max” is a sad story made palatable through moments of sentimentality and gallows humor. In other words, the film is a smorgasbord of cute and disgusting, hopeful and hopeless and sincere and cynical themes, frequently shifting between these dichotomous moods in the span of a single scene.

Compounding to the paradoxical tone, the entire work is narrated by Barry Humphries. His voiceover gives the film a sleepy, storybook charm akin to “Thomas the Tank Engine,” which persists even when the film dives to dark places. This narration, the cute animation and the recurring piano motif of Penguin Café Orchestra’s “Perpetuum Mobile” bring an element of whimsy to a story that could otherwise be too bleak to digest.

The film truly clicks when Elliot’s script balances out the plot’s darkness with impactful moments of sincerity. Before long, however, an established intensity rises again — when Elliot then uses humor to nip the sweet scenes down before they become cloying. Even so, some tone shifts can still be jarring, and the film’s darker moments — especially certain scenes in the film’s third and most depressing act — are too dark to be redeemed with an innocent one-liner about chocolate hot dogs.

A particularly poignant moment occurs midway through the film. Max admits that while he is proud to be an “Aspie,” one aspect of the syndrome that bothers him is his inability to cry when he feels upset. Mary responds by sending Max a bottle of her own tears, which she labels “teers for max.” The viewer is dumbfounded by this compassionate display, not knowing what to make of a prior exchange (only two scenes earlier) when Max reminded Mary that turtles breathe through their anuses.

“Mary and Max” is a tender story about a friendship that bridges the gap between age, continents and socioeconomic backgrounds. In essence, it is a story that manages to balance competing tones with exceptional success, and its gorgeous claymation still catches the eye 10 years later.

In 2019, let “Mary and Max” earn its second chance. In an age where personal connection seems distant and mental health issues dominate headlines, “Mary and Max” is a 10-year-old story that couldn’t feel more present.