It’s 1999, and the world is about to end. Computers are becoming ever-more ubiquitous and have been taking an increasing hold on the lives of the human population. Now that a new century is dawning, it’s all over. They can’t adapt the same way paper calendars can, and the second the clock strikes midnight on Jan. 1, 2000 — apocalypse.

The sky will illuminate with a firework display of nukes or rockets, or, nukes and rockets. Anyone unlucky enough to be traveling by airplane into the new century will probably just plummet back down to Earth once the worldwide electricity grid blinks off like a lighter flame caught in the wind.

Anything is possible in the year 2000.

Or, it’ll be business as usual. When the ball drops in Times Square, the way it does every year, the moment will be marked by cheers and excitement, rather than shrieks of panic and sirens signifying impending doom. The computer will adjust, the way it does every hour, moving into the new century, proving to be as ordinary as going from 11:59 p.m. to midnight on any other day. Airplane passengers will hardly notice, the way they always do, too tired from a long day of travel that placed them on a flight on New Year’s Eve, to process the pilot’s excited announcement: Welcome to the 21st century.

The world didn’t end in the year 2000. The fears were unfounded as the computers transitioned seamlessly into the new year. The preceding decade had already brought upon an unprecedented economic prosperity in the form of the not-yet-burst dot-com bubble, and now, the technological infrastructure had done humankind the ultimate favor, it put off the end of the world. Technology had proven its endless potential.

Lives in the new century would reflect the techno-utopia. Everything from fashion and furniture to music and architecture would embrace the aesthetic. Angular designs were abandoned in favor of globular elements, as if meant to emulate an oversized amoeba. Drab, muted colors were replaced with candy-bright hues and a metallic chrome, the unofficial shade of the future. To honor the computers for not ending the world, designs paid tribute to the language of technology, integrating the 1’s and 0’s of binary code. No longer satisfied with depictions of a simple human body, people welcomed images of cyborgs and aliens, or, at the very least, a simple human body modified by technology.

In the nearly two decades since the advent of the 21st century, the world’s vision of the future continues to shift, but modern-day pop culture has displayed a revived interest in the y2k aesthetic.

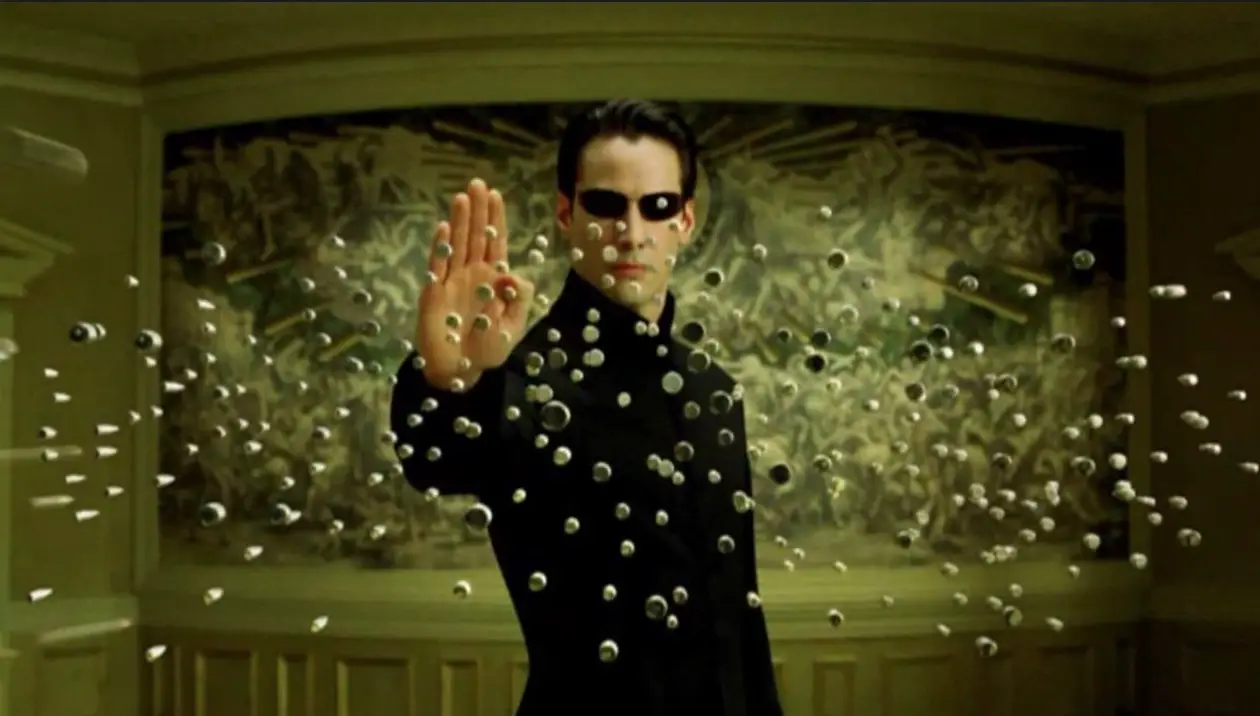

Pop stars, such as rising artist Rina Sawayama, have adopted the aesthetic and made it a central part of their image, both aesthetically and sonically. Charli XCX and Troye Sivan even released a tribute track entitled “1999,” with album artwork featuring the two artists dressed as characters from “The Matrix,” a film essential to the development of the early 2000s aesthetic. Dazed Beauty, a newly launched offshoot of the revered U.K.-based fashion magazine, has revealed a new logo featuring a bubbly font in a metallic silver that takes obvious inspiration from the visual trends of the early aughts. The blog Institute for y2k Aesthetics, which collects images of restaurants, electronics and fashion of the time period, has grown to more than 12,000 members on its Facebook group, as well as thousands more followers on its Tumblr page.

Trends are cyclical. Nothing in an industry ruled by the visual — furniture, cell phones, makeup, entertainment, where the only advantage can be gained by standing out — ever really disappears. The early ’90s had its moment in recent pop culture history, defined by reboots of Nickelodeon cartoons, the appearance of Crystal Pepsi at your local convenience store and the fashion industry’s resurrection of the Delia’s back catalog.

Now, it appears the world’s attention has inched forward a few years. It is a mostly futile task attempting to understand why a specific trend or aesthetic can suddenly capture the interest of the general public. But of all the movements primed for revival, the once buried fascinations ready to be exhumed, it feels appropriate that the y2k aesthetic should regain popularity in the world as it is today.

The world was enthralled; technology had presented a boundless frontier, careening users into the future, one portable music player at a time. There was no predicting what the future of technology would bring. As history loops back around on itself, the world is in a similar position today. The computers that were thought to be strong enough that a glitch could inadvertently destroy the planet have become infinitely more powerful and have shrunk down to the size of a pocket. Any given smartphone is more powerful than a supercomputer of the ’90s. What could possibly come next?

Barreling toward the unknown is the most treacherous path. Perhaps that’s why the aesthetics of history’s last technological boom are primed to make a comeback. The fears derived from the technology of the late ’90s (death, destruction, apocalypse) proved to be unfounded. The hysterics of the era were replaced with a playfulness, a lightness and a celebration of possibility. Now that our own technological innovations have brought us to a point of holographic pop stars, DNA hacking and a nearly non-existent expectation of privacy, the idea of lightheartedness, of an open-armed embrace of the future, would not go unwelcomed in a present day so often bogged down by fear.

It may be much simpler than that. Maybe these artists and brands are simply trying to capitalize on the nostalgic feelings the aesthetic evokes. After all, the target audience for these visuals would have grown up around y2k, experiencing the era as children, blissfully unaware of the responsibilities that would come to define adulthood. It’s the simplicity that makes the past so appealing.

It’s 2018, and the world has not yet come to an end, but nearly everything has changed in the almost two-decade interval since we thought a computer glitch would cause the nuclear apocalypse. Our global culture has shifted, our zeitgeist embracing what was once unthinkable, inching us closer and closer to the imagined future. Technology has advanced to a near dystopian level. Destruction may seem imminent, but it’s shaping up to be a slow burn rather than a quick flash leading to darkness. Perhaps the fear of the future causes people to become enamored with the past, yearning for the days when their worries were as simple as the end of the world.