It was an open-and-shut case in the court of public opinion for Harvey Weinstein. The allegations were damning, the evidence convincing and the consequences obvious. Weinstein was forced to resign from his own film production studio and his name is now essentially synonymous with sexual misconduct.

It was an ideal case to start the spark of #MeToo, but tragically, many of the cases that followed Weinstein’s forced resignation have been less clear-cut. Where Weinstein’s story was blown open by a star reporter, other allegations went public more messily, and the results were less consistent. Some celebrities resigned, some went on leave, and others just ducked and hoped for things to eventually blow over. Aziz Ansari and Louis C.K. are among those in the last camp.

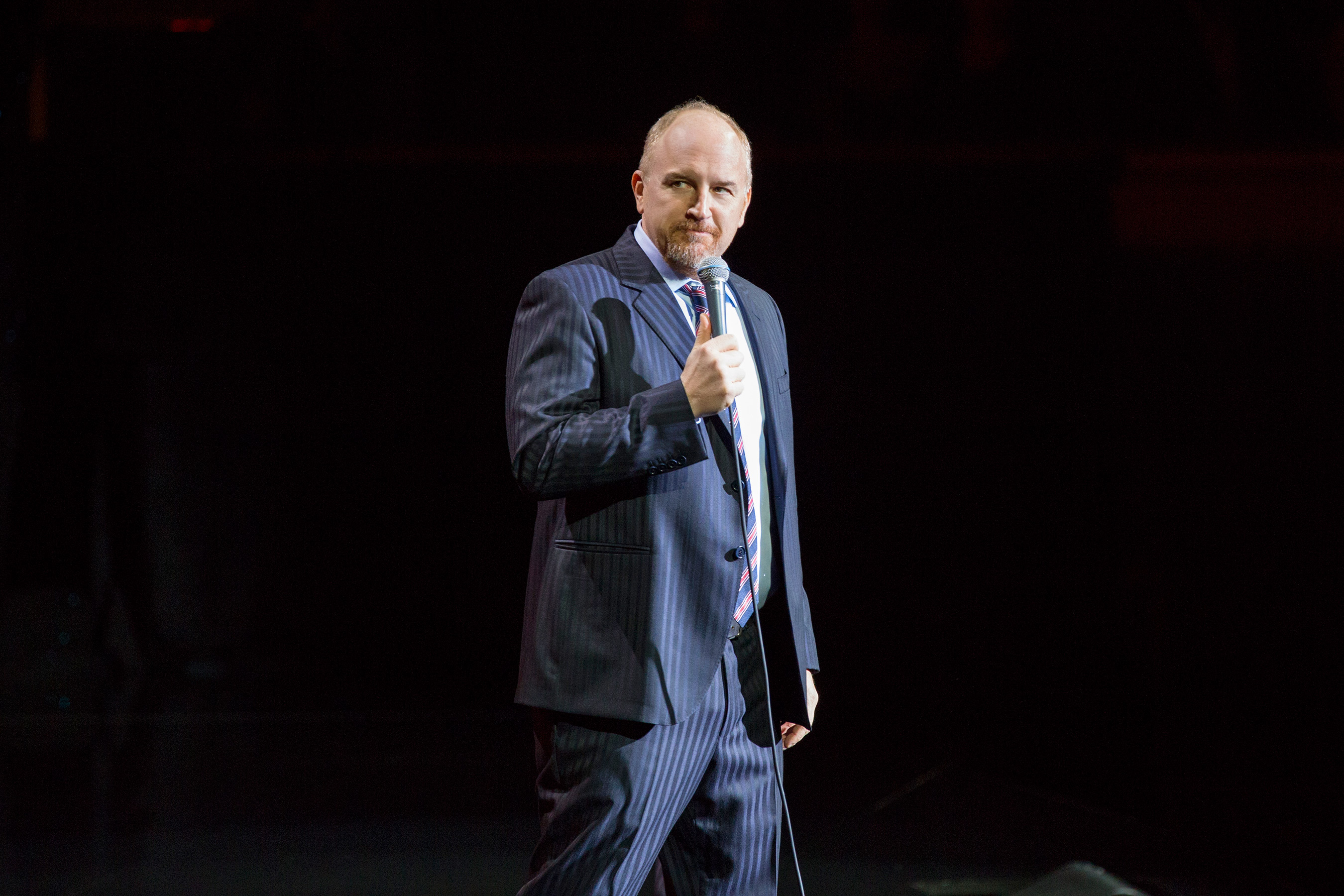

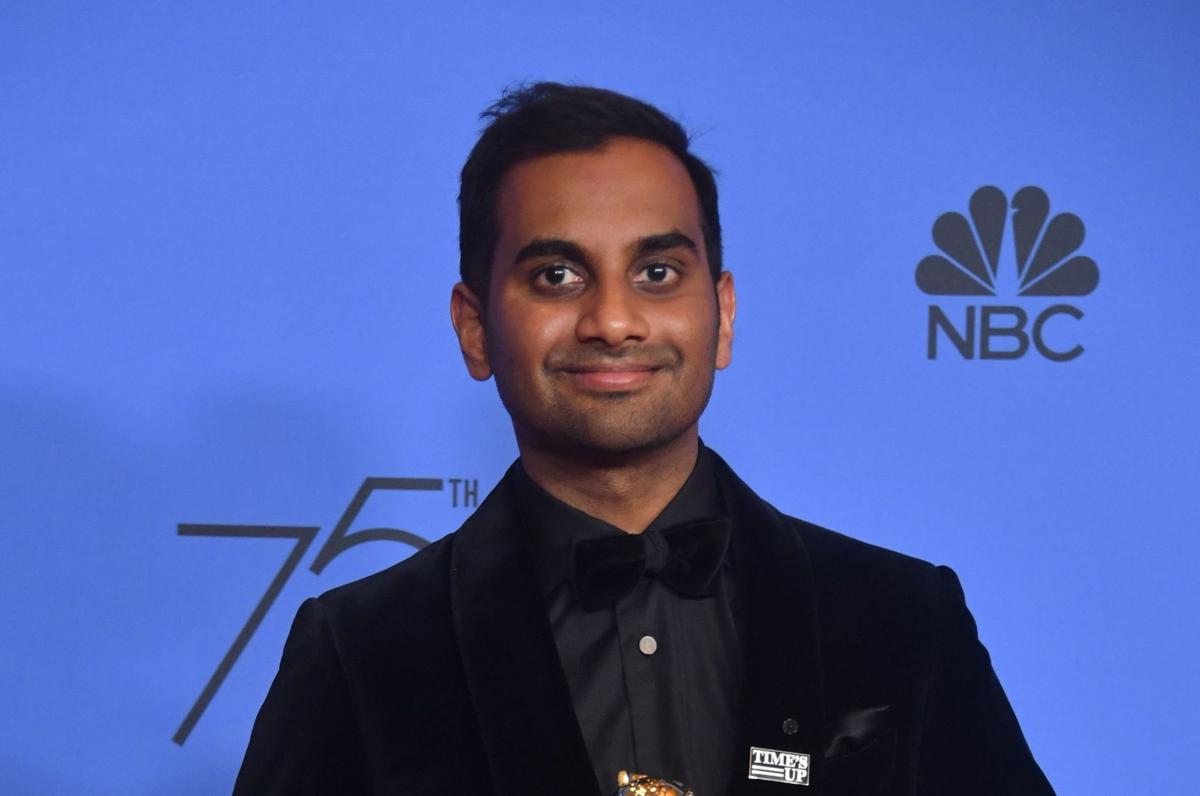

Both Ansari and C.K., mere months after the sexual misconduct allegations against each emerged, have returned to the stage. Unlike what would’ve happened if Weinstein had come back, the results have been… mixed. Some have talked about the vast differences between the two comedians’ cases, characterizing Ansari’s misconduct as an innocent case of missed cues, while C.K.’s crimes were repeated and totally nonconsensual.

In any case, the lack of a consensus in the court of public opinion has allowed both to come back, apparently untouched by the allegations against them in the long run, aside from the lost time. In other words, as long as there’s no clear consequences holding offenders like these accountable, they’re going to keep going back to work.

What’s missing from the discussion is an honest question that’s been brushed under the rug since the beginning: When, if ever, should it be considered acceptable for these men to return to their jobs? Until somebody gets down to brass tacks and really addresses this question sincerely, especially that first big “if,” cases like these will devolve into matters of opinion, which they clearly shouldn’t be.

First things first — it doesn’t make sense to let people come back just because audiences are willing to see them perform. I’ve heard this response from a couple of places, especially as it relates to C.K.’s club comedy sets. The logic goes that he should be allowed to perform if people are willing to watch him.

But that’s clearly not a good standard, because Cosby did a set after his first sexual assault trial was declared a mistrial. If people were willing to watch him then, should he have been allowed to perform, even though he was eventually declared guilty on three counts? Just because you can get away with doing something doesn’t mean you should do it, and the same logic applies here to the Comedy Cellar for hosting C.K.

Another popular defense is that C.K. and Ansari have waited long enough. Both took financial hits from their respective misbehavior (to put it lightly), and both took long-ish breaks from their careers to wait for the brouhaha over their actions to die down. As some have put it, they’ve “done their time.”

But “doing time” isn’t just taking a break, it’s going to prison, something that neither of these guys did. What’s the idea here, that you can be forgiven for relatively serious sexual misdemeanors if you take a long enough vacation afterwards? That’s clearly ridiculous.

Instead of having offenders’ time off be totally arbitrary, it makes a lot more sense to have it be relative somehow to what they’ve actually done, and since we’re talking about careers here, the solution ought to have something to do with that as well. Although accounts still differ about the nature of Ansari’s actions, the thing that can be agreed on is that it mostly revolved around one private event. C.K., on the other hand, admitted to several accounts of professional misconduct, events where he victimized other writers and comedians.

With that in mind, the decision to allow C.K. back on stage becomes a lot more sinister. C.K.’s actions almost certainly alienated his victims from comedy at least temporarily, so letting him take up the mic again should take the moral backseat to the priority of making sure his peers have recovered from his actions. In short, if the comedians and show writers that C.K. victimized don’t feel safe returning to comedy, neither should he.

It’s going to take a long time to figure out how to treat strange circumstances of justice like these. Part of the problem is that this all takes place outside of a real public courts system, so despite what might be the just thing to do, comedy club owners don’t have much incentive not to allow dubious comics to get back to business as usual.

It’s going to take clear discussion of the consequences involved with sexual misconduct in order to start getting things straight. Until then, people like C.K. are just going to keep taking long vacations instead of facing justice.