You are sitting in a crowded room, surrounded half by strangers and half by people who know you, but everyone feels unfamiliar. You are overwhelmed by the heaviness of the room. If your mind could foretell the forecast outside, you’d predict storm clouds. Such is life with a panic disorder

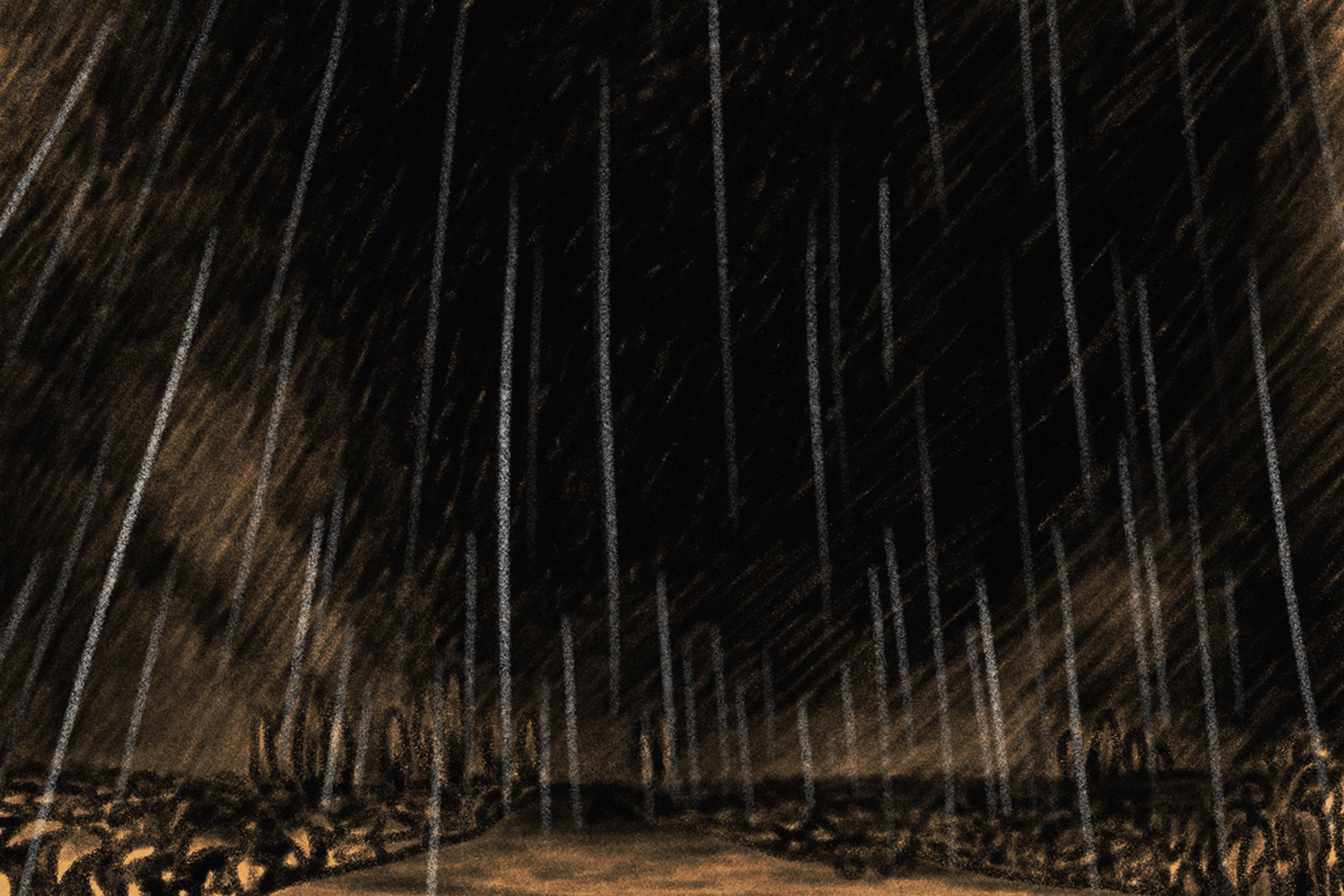

The weather is fickle. Its changes are intermittent, as sporadic as the body’s response to raw terror, the visceral feeling of losing control and as volatile as a natural disaster — hurricane or cyclone. The onset of a storm is as erratic as a panic episode; it feels like sudden death. When it rains, you don’t need to see the skies overhead to know it is a stormy day, you can feel the storm building within your veins, red-hot, feel it skin-deep — a sense of worry burns through the flesh and the bones. Panic has its own heartbeat.

You know cloudy days are on the horizon when you find yourself feeling hollow and hyper-vigilant, on the lookout for some indiscernible threat, apprehensive. When you feel a storm incoming, you discern a subtle change in the energy and atmosphere of the room. Your mind triggers you to retreat, take flight, fight or freeze — the body’s natural stress response.

Your vision is clouded by fear so intense, it causes you to dissociate at times, yet you are lucid, feeling an eerie sense of peril encroaching upon you. Something terrifies or petrifies you. You’ve taught yourself to pay attention to changing weather patterns. Too many hot days followed by days full of cold air and low temperatures spell out disaster, aka tornado.

You’ve spent your life storm chasing, and it’s taught you how to distinguish between a level three disaster and a level five. You’ve conditioned yourself to use the weather to track the unexpected. You know nothing is as spontaneous as an infrequent eruption, but you’ve trained yourself to believe you can prepare against worry and curtail the onset of panic by developing a system of detection for what would normally be categorized as out-of-the-ordinary or out-of-the-blue. Blue is good; gray is what defeats you.

You know weather can be unpredictable; that’s what makes it destructive. You feel a sense of trepidation on days when your headspace is bleak, seemingly full of dread and panicky thoughts, because you know overhanging clouds are the most ominous when you can’t see beyond or through the haze. You just feel the opaqueness of a gloom and doom that won’t go away, a darkness that won’t yield to lighter days. You feel the shrinking of a thousand sun rays.

The immensity of light can’t reach you, can’t touch you in the darkest corners of your mind. You are full of fright, oscillating between a fear of safety and a fear of danger. The second fear is normal, rational. The first isn’t — what could be scary about feeling safe? Well, the threat of feeling unsafe, the fear of not knowing if what you think is safe could actually jeopardize you. The fear of placing yourself in a precarious situation by doing something to control your panic or doing nothing.

You fear yourself and others. But it is not yourself you fear; truly, it is your mind, your pounding heart, your racing blood pressure, the fear of being smothered or suffocated due to the paralyzing sense of disaster you feel that results in your literal immobilization.

Fear of immobility often manifests itself through reoccurring thoughts of lurking catastrophe, emergency and the thought of having no exit strategy, no plan, no escape room, all of which elevate your tension, exacerbate the fear and distress you feel.

Your fear is paramount. The storm is approaching, almost upon you; it’s do or die time. Fear is your friend now. Like thunder and lightning, the constancy of your anxiety and apprehension comforts you. The presence of the rational helps assuage the discomfort you feel toward the presence of the irrational and the absence of the ability to determine what is real.

Storms, like panic attacks, are disruptive, but they are primarily a response to a condition that has been besieged by an environment that is disturbed. Something alerts or signals the system in place to the presence of an invader, one that does not belong. When this happens, the system attacks so as to bring itself back into balance and remove the threat, ward itself, defend against the existence of something that threatens its survival. When a state of nondescription returns, conditions will return to normal and the storm will subside.

You know how thunder rages. You can almost taste the boom, clap, crack before you see the lightning strike. You are well-attuned to the sound of clash and clang and fizzle; it fills you with alarm. You tremor, shake, shiver some more. Your body is registered to noise, key to respond to danger. You sense it like your dog senses meat or a killer smells fear. Your trepidation radiates off of you, or does it? Can anyone see it but you? Perhaps to them, the weather outside is unimportant. They can’t sense the thunder or the rain. It’s just a crowded room. You want to scream “A storm is coming, a storm is coming, a storm is coming,” but it’s no use.

Your mind is cloudy, a striking gray. You feel a chilliness within your bones, yet, your body is overheating. Your skin is hot to the touch; you can feel your palms sweat as they shake, yet, your whole body shivers like you’re hypothermic, like you’ve just been pulled out of a deep layer of permafrost after confronting a chilly blizzard in the middle of a brutal Russian winter. Your shadow is your silhouette; dark is the only home you know. That’s why you spend your days chasing storms.

Why are you sweaty? Why are you drenched in shadows? Why are you shaking? Why are your eyes dilating, growing wider as your skin becomes filled with goosebumps? What are you so afraid of?

What are you more afraid of, what you know or what you don’t know? What scares you more, that you can’t control the shaking, the movement of your body against your will, or you can’t prevent yourself from standing still?

What is more distressing? The fact that you can’t run because you’re paralyzed by fear, or the fact that even if you could, you wouldn’t, because you don’t know where to turn?

What happens when you feel as though you cannot reside in your own body? When you feel as though you cannot trust your instincts, your thoughts or your mind? When every muscle in your body tenses as your body releases stress hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol?

You experience an automatic physiological and psychological response and have a physical reaction to the perceived threat you fear. Your body enters into a system of defense. Your evolutionary survival instincts kick in. You could be in a room full of people, but you feel remote, isolated, separate from the rest as if they are all invisible.

Your heart rate accelerates. Your heart pounds inside your chest and your hands and feet tingle uncontrollably. You experience yourself as unreal (a trademark of derealization) and disconnected (a feeling marked by depersonalization), early warning signs of specific mental health problems.

You get chills. You can’t shake the feeling of your impending doom. It rattles and frightens you, intimidates you into silence even though you want to scream for help. You locate pain in your stomach, your lower abdomen. You might hyperventilate. You might even feel nauseated. You are frozen in fear, so you may struggle to breathe well, taking rapid breaths or exhaling shallow, ragged breaths. Your extremities (hands and feet) might feel cold as blood rushes through your more vital organs, causing the rest of you to feel feverishly warm.

Your body sends reactive signals to the rest of your brain to alert you of danger, even though it is unwarranted — you are not in a life-or-death situation, but your body is convinced you are endangered and imperiled. You exhibit the symptoms of a panic attack, and when it happens enough times, triggering your body into fight-or-flight despite the absence of a life-threatening event, you are diagnosed with panic disorder, an anxiety disorder that’s extremely debilitating and marked by more than just nervousness. You realize your mental health matters.

Mental illness is a lifelong fight. I’m here to tell you that it’s not all in your mind.

Panic disorder doesn’t have to be a death sentence. Panic disorder is not always a response to trauma history or stressful life events. Anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and childhood trauma can also stimulate a conditioned fear response in the body. Negative association, stimulus generalization and over-identification with painful or stress-inducing memories or difficult life experiences can induce the strain or toxic stress needed to induce panic attacks.

I’m someone who has experienced all of the above, which explains how that trauma history resulted in my development of panic disorder. I have been defined by intense fear and anxiety, unshakeable waves of nausea, dizziness and so much more. I have shaken and stirred for hours, in chills and hot flashes, and I have felt unreal and totally detached from myself, fundamentally reduced to a choking feeling in the back of my throat and the sensation of a thousand knives in my gut. I have been overcome by stimuli and my days have been spent watching storms. I’ve lost count of the number of panic attacks I’ve had, the number of crowded rooms I have had to escape and the number of times I have mistaken the light of my body as a silhouette, so accustomed to my own shadow.

A panic attack can be so severe it can be mistaken for a heart attack if you are not careful. Learning how to manage the symptoms of panic disorder, among other mental health disorders, and seeking treatment can save your life; it certainly saved mine. Perhaps you can then stop checking the horizon for signs of storms. Stormy skies can simply be what they are instead of a sign. You don’t have to spend the rest of your days being a storm chaser.