In the era of Black Lives Matter and Trump, there is a constant questioning of who is allowed to be political, and when. This is especially true in the world of professional sports, an assertion that the recent debate over kneeling during the national anthem attests to. These days, “Shut up and play” is a disappointingly common mindset.

This attitude also holds, however, in other arenas: Comedians are often told that they shouldn’t make political jokes and musicians are told not to venture into social issues. Art is often held as this lofty ideal, separate from everything else that is going on in the world. This view of art, though, strips its ability to be a force for change in the world. As a result, many artists push back against the concept by making intensely political creations. As the great Nina Simone once famously asked, “How can you be an artist and not reflect the times?”

Painter and Louisiana State University (LSU) sophomore Chayse Sampy agrees: She strongly believes that art should be involved in social issues. Her paintings, which deal with the realities of racism and stereotyping, address these issues head-on. “As artists,” she says, “It’s historically been our job to comment on the state of the world.”

Her work is powerful, not in spite of the fact that it addresses issues that people often want to avoid, but because of it. “Sometimes you have to talk about these things,” Sampy says. “Most people don’t want to talk about politics, most people don’t want to talk about racism — most people don’t want to talk about anything negative, so I’m here to show them those things.”

Her paintings are inspired by racial justice and social justice — any issue, she says, that has a social consequence. These are issues that people know about, but that rarely get addressed. Sampy points out that because racism in particular is such a deeply entrenched, underlying issue in society, it’s hard get people to pay attention to it over time.

“America is so fast-paced,” she says. “We forget about the issues so fast. But artwork lasts forever. I could repost the same picture over and over again and keep the conversation going.”

Sampy says that other people’s reactions to her art also inspire her. Since many of her pieces are not light-hearted or happy, they often make audiences uncomfortable. This is 100 percent intentional: She wants her art to force people to self-reflect and rethink their beliefs.

The sophomore began drawing as a kid, but she didn’t start painting until her junior year of high school. She comes from an artistic family: both her mother and grandfather are artistically inclined, and even her dad doodles.

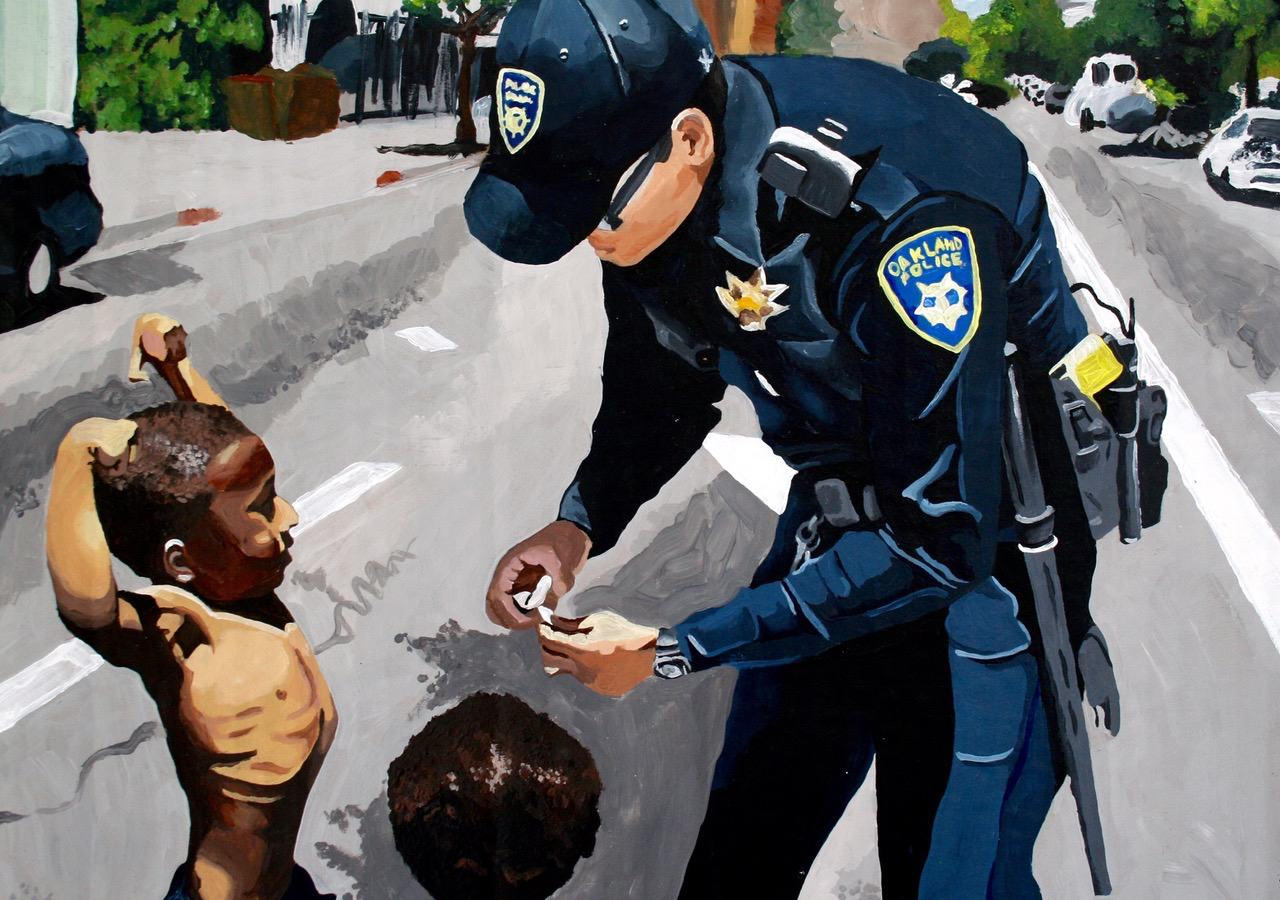

Also in her junior year, when more and more news stories of unarmed black men being killed by the police emerged, Sampy began to make racial issues more of a focus of her art. This is when she first started to consider art as an option for her future. During this period, she created a series of paintings about issues in the black community. Sampy says that this was the first time her family started seeing that she had a real purpose with her art.

Since her early beginnings, Sampy has grown to be a much more technically adept painter, something she credits LSU for. Through learning more about the history of art and how to use different techniques, the young creative has evolved as an artist. Her more recent work is less literal and more abstract, as opposed to her earlier, more photorealist work.

Sampy works more in an Expressionist style now, something that she feels works well with the subject matter of her paintings. Expressionism allows artists to show a lot of emotion in their work, something that Sampy finds to be a useful tool, especially when dealing with emotionally charged issues like racism. “I’m a very emotional person,” she says, “and art is what I channel my emotions into.”

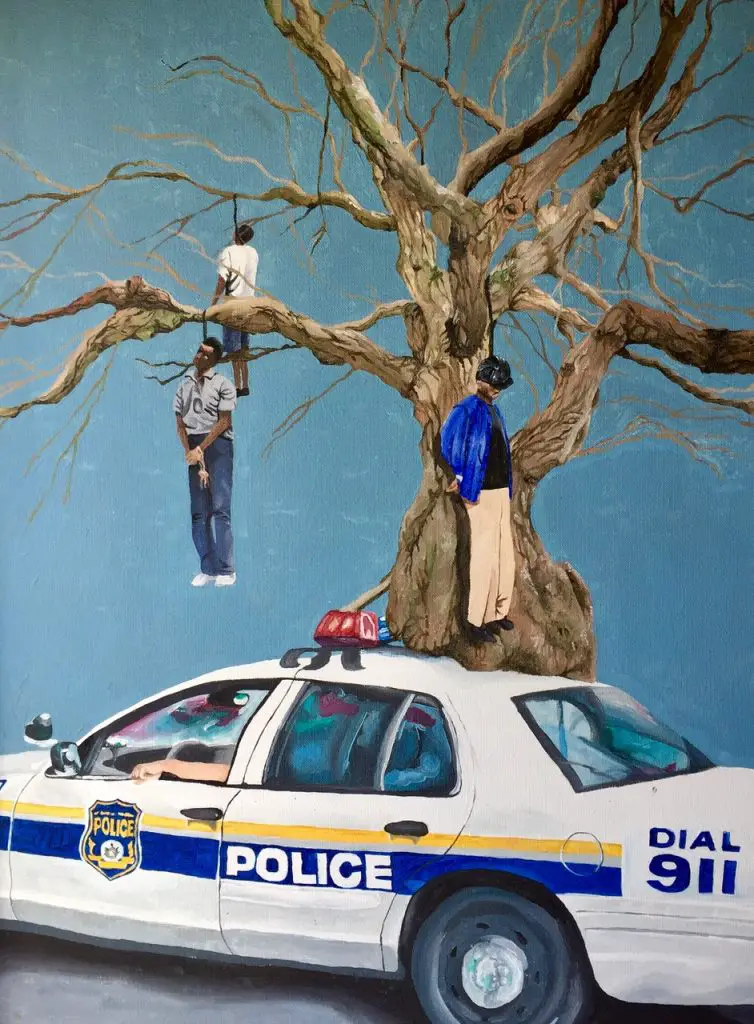

Perhaps her most iconic piece is “Modern Day Lynchings.” In it, a tree grows out of a police car. Three black men hang from the tree.

Sampy made the painting in the immediate aftermath of the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, both of whom were unarmed black men shot by police officers two years ago, in the span of a couple days.

“The fact that police officers can get away with it,” Sampy says, “and that there are no repercussions and it’s happening so frequently — it’s kind of like a modern-day lynching. These people can go back to their regular lives after. There’s no accountability.”

This is the connection she wants to make with the painting: one that forces the viewer to consider the uncomfortable idea that something akin to lynching is still happening in the U.S. today. Even when people are aware of the issues, though, they often don’t do anything about them. Sampy sees this as a problem with how people engage with black issues.

“Everyone claims they want to be woke, everyone claims that they know black issues,” she says. “You can talk about it all day on Twitter, but you’re not investing in black businesses, you’re not helping people that you know that are starting businesses, trying to do something. Nothing’s changing, we’re just talking about it.”

Sampy wants to see a black community that works to uplift its members and support black businesses and other ventures. She points out that university-alumni communities do something very similar with a lot of success. Supporting black issues on social media is the bare minimum; investing in the black community is far more helpful.

“Even with my art,” Sampy says, ”people say, ‘Oh, that’s so deep’ — but they’re not going to put money into it.” This investment in black art and businesses, she argues, is essential to creating real change.

In the future, Sampy wants to bring about this change by creating spaces in urban communities for children to discover art and develop their own abilities. “There’s a lot of poverty, a lot of gang violence, a lot of gun violence because these kids are growing up in a cycle,” Sampy says. “They get into these things to survive — but I don’t think life should be about surviving.”

Sampy sees art as a great avenue for giving kids something beyond mere survival. “I feel like kids need something that’s gonna slow them down and make them self-reflect and grow as people,” she says. “Art does that. It makes you slow down, pay attention to detail, pay attention to the world around you.”

Sampy says that art, as a form of self-expression and self-reflection, is similar to rap: It gives children a new outlet for their emotions and their experiences. She also says that because she didn’t see a lot of black artists growing up, she didn’t realize that the visual arts were a viable option for her, so she didn’t make the decision to go into art until much later.

Representation, as always, matters. As black art gains prominence and as programs like the one Sampy envisions are developed, kids will have more opportunities than ever in the art world.

In terms of the future of her art, Sampy doesn’t see herself running out of issues to cover any time soon. She is currently in the initial stages of planning a series called “Make America Great” in which she wants to depict what she says “would actually make America great.” This direct engagement with social and political issues is something Sampy says will continue to focus on.

“There are so many issues out there, I’ll probably never run out of things to paint,” she says. “I just have to figure out how to paint what I’m thinking, or feeling.”

You can find Chayse Sampy at her website, https://chaysetheartist.com/.