Most people don’t see the lack of access to menstrual hygiene products as a problem in the industrialized world — it’s often seen as more of a “third-world issue.” However, even in the U.S., there are still significant barriers to access for people of all genders who menstruate.

There is, of course, the infamous “Tampon Tax”: 37 states in the U.S. tax tampons as “luxury items.” Because of this tax, pads and tampons are excessively expensive for women living in poverty.

In correctional facilities, this situation can be dire: There are countless horror stories from incarcerated women about being denied access to menstrual hygiene products. Pads and tampons are also rarely provided for free in public schools, making the simple act going to class that much harder.

Menstrual hygiene products are absolute necessities for people who menstruate — and yet, they are rarely treated as such by institutions that could easily provide them for free. In recent years, though, there has been some progress on this front: New York City is implementing an initiative to install dispensers in hundreds of public schools, donate pads and tampons to shelters and ensure that inmates’ rights to menstrual supplies are not violated.

Brown University, NYU, the University of Minnesota and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln all provide a free supply of pads and tampons in restrooms on campus. Although this is certainly progress, much more needs to be done to ensure that everyone has access to menstrual hygiene products.

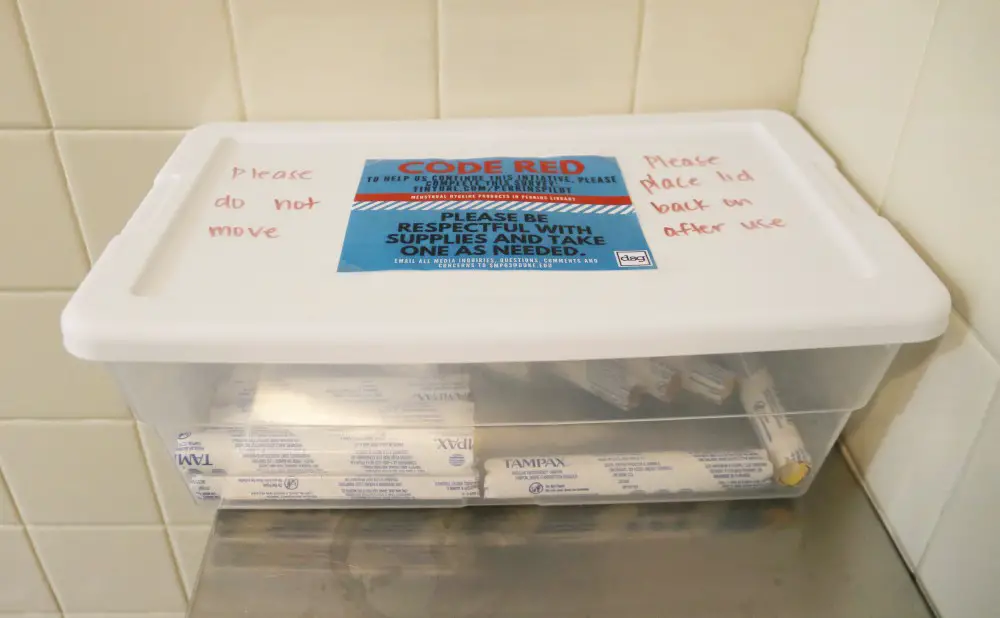

Sabriyya Pate, a junior at Duke University, is leading one such initiative to expand access to menstrual hygiene products on campus called Code Red. As part of the initiative, Pate and other volunteers supply containers in women’s and gender-neutral restrooms with pads and tampons.

Ultimately, they plan to use the data they have collected over the course of the program to convince administrators to place free dispensers in all of the restrooms in the main library on campus. Pate hopes to convince the university’s administration that expanding access to menstrual products in more places on campus is absolutely necessary.

Rakshya Devkota: What is the mission, or goal, of Code Red?

Sabriyya Pate: Code Red is an initiative that we began here at Duke with the goal of creating a pilot program that demonstrates a need for the university to provide menstrual hygiene products in all the restrooms. It started with a program in Bryan Center, which is our student center, which happened last year.

This year, the pilot program — which is completely student-run — has been implemented in Perkins Library, the major library on campus.

Every week, we have a team of volunteers restock tampons and pads in the Perkins Library, then we collect data on how many are being used. When we run out of supplies, we’ll take all the data that we’ve collected and write it into a proposal to our administrators to show them that “Hey, this is something that students need: it’s something that we owe our menstruating students faculty and staff, who make this university great.”

Menstrual hygiene equity is a fundamental right, and we’re very privileged to be at a university that has the capacity to satisfy these hygiene needs, just like how it provides toilet paper and soap. There is no reason for these kinds of hygiene products to not be provided for free to our menstruating community members.

That’s the philosophy behind Code Red, but also tactically, it’s part of a plan to demonstrate a need for the university to take ownership over this program — because as it stands, we can’t keep having students take the initiative to do this.

It’s all about getting our universities to get housekeeping and our facilities management on their end, administratively, to provide hygiene products in all the restrooms.

RD: One thing I think is really great about your initiative is how inclusive it is — like how you put menstrual supplies in both men’s and women’s bathrooms. Can you talk about why that inclusivity is important?

SP: Well, initially, we put bins in the men’s restrooms. Unfortunately, the supplies were not being respected and the container disappeared, so we’ve moved now to having the dispensers in the women’s and the gender-neutral restrooms. The whole philosophy of that is, as you know, gender is constructed and there are menstruating individuals of all gender identities.

We just want to be inclusive of individuals who may identify as male but also menstruate, and so having access to resources such as tampons and pads in the restrooms that they use is very important.

RD: You said that the menstrual-hygiene access initiative started at the student center originally, and you’re branching out into the library now. Do you have plans for the future for other places you want to implement it in?

SP: For the Bryan Center, the university just did it — they bought dispensers, bought the supplies and housekeeping from the start has been restocking, so there has never been a student-run initiative around that.

For the Code Red program in the library, we don’t use dispensers, we just use plastic containers that have pads and tampons in them. This is the first student-run initiative on campus that is actively restocking them.

In terms of if we plan to extend the program: we feasibly cannot. The way the student activities fees work is they have certain rules for what that money can be used on, and one of those rules is that it cannot be used on hygiene products.

We were able to get special approval to buy these hygiene products because it was a pilot program, but in the future, I don’t anticipate that we’ll be able to do that because of university rules — and ideally, students shouldn’t have to restock these bins every week.

The university would take on that responsibility and provide it as a service to students, faculty [and] staff, just like it does with toilet paper and soap.

RD: Where did the idea to expand the Bryan Center initiative come from?

SP: I think it’s important to clarify that it’s not really an expansion of the Bryan Center program. For that, through my involvement in student government and [with] other student group leaders, I had approached the university asking them to explore a Bryan Center initiative, and eventually, the university did implement it — and there were never students actively running it.

So in that case, there was policy written, a memo, a meeting and then it was implemented.

Afterward, we got a lot of feedback along the lines of, “Yeah, the Bryan Center’s great, but it’s not where students spend a lot of their time.” People spend a lot of time, however, at Perkins. And so we were thinking, “Okay, how can we get the university to have the program in Perkins?”

We heard from the administrators that they think that having it in the student center alone is enough. But as you can imagine, it’s a lot to ask somebody to walk from wherever they are, be it the library or a classroom, all the way to the student center, just to get hygiene products.

And so the library is a more central location on campus since it’s where students spend more of their time, so that’s why we had it there.

And I should say that before I even approached this for the library, I was thinking about access to menstrual hygiene as an RA. I used some of my RA funds to buy plastic containers, tampons and pads — and for the past two years now, I’ve been trying to restock that for my residents, 200 or so people.

People love that if they don’t have tampons or pads and they get their period, they know they can get supplies in their own dorm. So having seen success with that, a year before I even began this whole Perkins thing, I had the idea for the pilot.

RD: What is your role as the leader of Code Red?

SP: I honestly don’t have an official Duke Student Government committee title: This is just something that I’m passionate about, that I did as an RA. I’ve just been leading this as someone who knows how to write policy and organize and reach out to so-and-so to get this budgetary statute approved, to order supplies and so on.

In terms of my official title, I lead the initiative, but Code Red isn’t an official movement or anything — we just organized organically around this issue [that] we think is pertinent on campus.

In terms of the volunteers who are restocking, it’s myself, a member of Duke Student Government’s Equity and Outreach committee and two members of Progress Period., a group on campus that’s all about menstrual-hygiene issues and talking about menstrual and sexual health.

RD: You mentioned your experience as an RA kind of led into how you built the initiative. What do you think are other experiences you’ve had that helped you take on that role?

SP: I went to an all-girls high school, where we were provided with menstrual hygiene products in our restrooms, and so for me personally and also for my friends, that was so critically important for our own empowerment. In this environment where we’re working hard, the library, we shouldn’t have to worry about where we are going to get our next supply.

Also, it was a symbolic gesture from the school. I remember it was my junior year of high school when the school began doing this, and it was really impactful to see that that “Wow, my high school cares about the needs of our menstruating students so deeply as to provide baskets of tampons and pads in all academic buildings’ restrooms.”

And just knowing from that experience how helpful it was for me and for my friends, how empowering it was, I knew that it was something I wanted to continue here at Duke.

I can also say, I am originally from northern Nigeria, and I’ve heard stories from my mom and grandparents about what it’s like to not have menstrual hygiene products. It’s very much a Western privilege to be able to have them at the student center, even if they’re costly.

So it’s very much invigorated this belief of mine that in these circumstances, because it is such a fundamental right, because there are people who never had these rights, it’s so important that I’m trying to support students on campus who are experiencing similar struggles.

Whether or not it’s because you’re from a low-income background and have the additional burden of having to purchase these [products] with the few extra dollars you have on hand, it’s just so important to make sure that everyone is feeling supported, and that they don’t have to miss class.

I think not only do we have a responsibility to provide menstrual hygiene products for us here at Duke, it’s also really important to support menstrual equity in areas that are far less privileged.

I think it’s just part of doing good in the world: that mindset that we have a responsibility to support those people and to be cognizant of our privileges. The last thing I want is this to be about people at an elite university only thinking about their own needs without recognizing the breadth of the situational context of their privilege.

RD: You mentioned a lot of things that seem like they could be an extension of what’s happening with Code Red, so I was wondering — how do you envision the future of Code Red, and beyond that, the future of movements providing menstrual supplies on Duke’s campus and beyond?

SP: I think we’ve seen more recently, in response to the Florida shooting, that student activism is taking a more predominant role in the public agenda, and so I’m really just generally excited to see a lot more young people — I have sisters who are 17 and 16 — who are riled up about issues they care about.

I’m hopeful that this will be one of those issues. In the past decade alone, we’ve seen so much progress being made in the area of menstrual equity, from various elected officials taking on the initiative to get rid of the tampon tax and providing hygiene products in public high schools. So I’m hopeful about that progress.

I also know that in the post-Trump era, a lot of activism has emerged to encourage women to run for elected office, and I think that will do a lot. Because at the end of the day, when you have women in office, when there are female representatives in positions of leadership, they’ll be able to act on the interests of the entire population.

And I think maybe the reason why menstrual-hygiene issues haven’t been addressed in the past, along with several other issues related to women’s rights, is because there is no poor-female representation in these echelons.

I’m hopeful that, on campus and nationally, this is only part of a larger trend. It’s exciting that Duke and Code Red can be a force in Durham to promote this, in addition to all the great work that university students across the United States and all over the world are already doing.