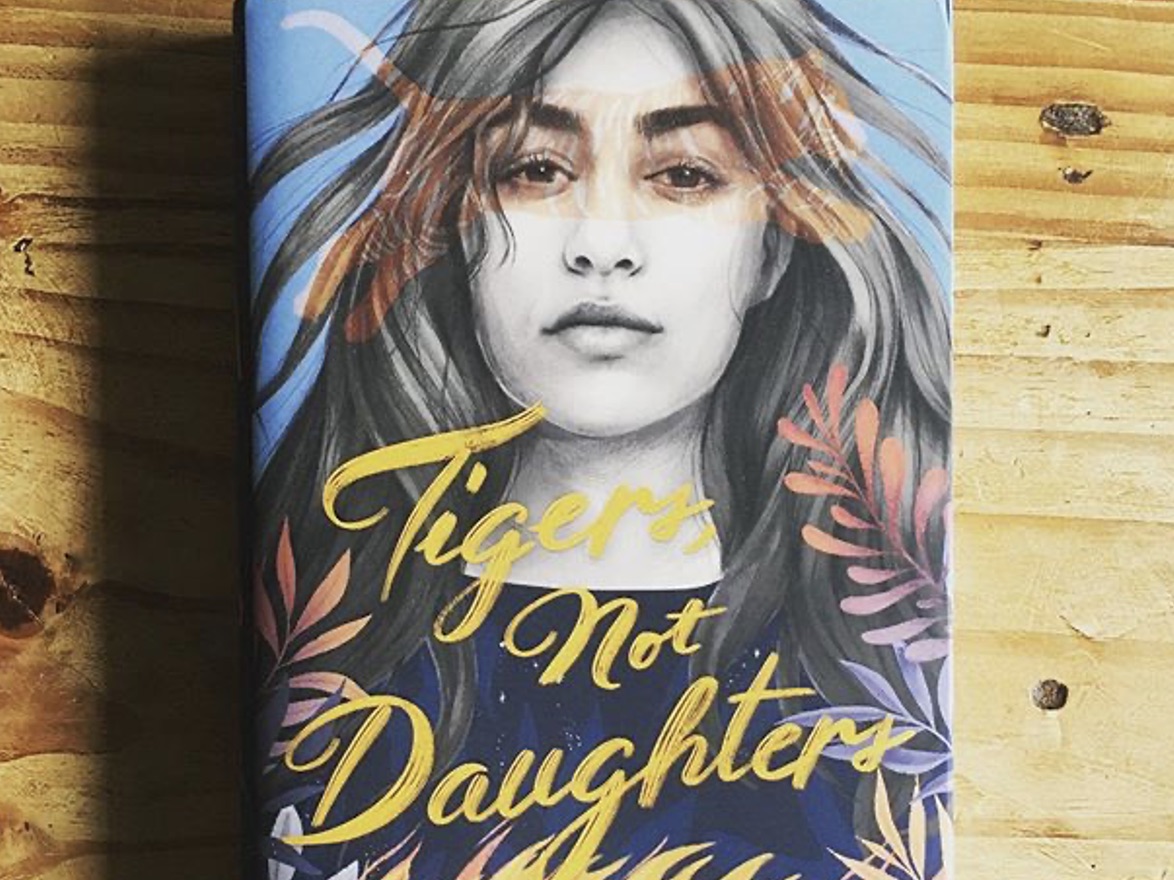

Grief can often bring people together. Seeking help from others can help ease sadness, and individuals can find the guidance they need within their family or community as they navigate the grieving process. But how does a family cope when their anchor is the one who passed? And what if she were to return, not as her former self, but as a ghost? In “Tigers, Not Daughters,” Samantha Mabry explores answers to these questions with eerie aplomb.

“Tigers, Not Daughters” tells the story of the Torres sisters, Jessica, Iridian and Rosa, as they grieve the death of their eldest sister, Ana. Each of the girls looked up to bold and confident Ana, following her lead when they tried to escape during the annual Fiesta celebration in their San Antonio neighborhood of Mexican-American families. However, their plan is foiled, and shortly after the attempted escape, Ana suffers a fatal fall from her bedroom window.

Now lacking Ana’s guidance, and her sway over their deadbeat and volatile father, Rafe, the Torres sisters are left feeling stuck and grieving in their own ways. Jessica grows irritable while trying to embody her older sister, even dating Ana’s abusive boyfriend, John; Iridian turns inward, reading Ana’s books and writing her own stories; and Rosa seeks solace at church and in nature, trying to communicate with a coyote who she believes holds Ana’s spirit. When Ana comes back to their home as a ghost, the girls must try to understand why Ana has returned.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B6Vr5KrA3iR/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Mabry writes the story from each of the girls’ perspectives, alternating between them and covering different time periods before and after Ana’s death. She also includes sections narrated by a chorus of neighborhood boys, one of which lives across the street from the Torres sisters. From his house, the boys watch the sisters, narrating from a first-person plural point of view to express their perspective.

The unique narrative style of “Tigers, Not Daughters” makes the book distinct. Novels that utilize multiple points of view are already uncommon, but rarely does an author also use different types of viewpoints as well.

The sisters’ third-person singular points of view allow the reader to know what is happening inside those characters’ heads, but they still maintain a certain degree of distance by forgoing the directness of a first-person narration.

In addition, having the sisters’ individual perspectives during conversations with each other gives each girl her own voice while providing the nuance that a one-sided narrative sometimes lacks.

Mabry writes each of the sisters with adept characterization and complexity, using the multiple viewpoints to show their similarities and differences.

Jessica’s voice is often imbued with irritability and anger, but her confidence falters when she tries to take care of herself. Iridian expresses the pain brought on by bullying and parental abuse, clinging to the characters in her favorite books for solace. Rosa’s voice is calmer, kinder and more curious than those of her sisters, but she bears the burden of managing conflicts between her sisters and father.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-IQF2jACEr/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Sometimes the many viewpoints lose their potency or become unbalanced, with one sister’s voice dominating the narrative. Mabry does the most justice to Jessica’s arc, giving her character more nuance as the story goes, while Iridian remains more static throughout the novel. But overall, having each sister speak for herself makes their motivations clear and authentic.

In contrast, the boys’ collective point of view complicates the clarity of a singular narration, leaving individual opinions and responsibility shrouded in uncertainty. Using the pronoun “we” to tell their side of the story, the neighbor boys serve several functions. As the only outside perspective on the Torres sisters, they both represent and comment on the gossip of the neighborhood — sometimes reinforcing and sometimes challenging the sisters’ own portrayals of themselves.

For much of the story, the boys regard the Torres sisters with curiosity and awe, imbuing them with a legendary quality and inhabiting the male gaze.

But most significantly, the boys serve as a commentary on the toxic masculinity of their neighborhood. As they witness the mistreatment of the Torres sisters at the hands of John and Rafe, they grapple with their own roles in their community.

Torn between being cool and masculine and doing the right thing, they express guilt at their own complicity. In one chapter, when they fail to act in support of Jessica, they remark, “It was one of the many times we could have said or done something and, instead, we said and did nothing.”

The boys’ role in the lives of the Torres sisters is just one example of how human relationships influence the sisters’ grieving processes in the story. As Jessica, Iridian and Rosa grieve, they each become more stubbornly independent. But when Ana’s ghost shows up, it becomes clear that she is trying to help them. As the sisters attempt to understand Ana’s ghostly appearances, they work together more and rely less on themselves.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B5LTapbAmde/

Thus, the biggest strength of “Tigers, Not Daughters” is its ability to show how vulnerability and independence go hand in hand. While John and Rafe undermine the girls’ confidence and push them apart, the sisters find strength when they work through it together.

And as they connect more throughout the story, they still maintain their distinct identities; in fact, they achieve even more independence as they become less tied down by others. When Jessica realizes who is most important to her, asserting that she is “fed up with men trying to leave their bruises all over her and her sisters,” they all can finally take action to protect each other.

In a recent interview, Mabry described Shakespeare’s “King Lear” as a major inspiration for “Tigers, Not Daughters.” She said, “A few years ago at a performance of Shakespeare in the Park I was struck by the line about how Regan and Goneril were ‘tigers, not daughters’ because of their cruel treatment of their father. I thought that was such an interesting phrase and wanted to write a story in which it could have a more nuanced meaning.”

The story of Jessica, Iridian and Rosa Torres provides that nuance, flipping daughterly duty on its head and instead foregrounding the power of sisterly bonds. “Tigers, Not Daughters” provides a poignant reminder that, in the face of grief and adversity, relying on those you love — whether alive or dead — does not undermine your own individual strength.