The only thing the unnamed narrator of Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 sleeper hit “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” wants is to do absolutely nothing. Moshfegh’s protagonist is distressed by her New York lifestyle, working at an art gallery while navigating a very interconnected friendship with her best friend. Disappointed in the life she’s living and the world around her, who wouldn’t want to fall into a self-medically induced coma for a year? The world is hell in 2001, Bill Clinton’s fighting for the last gasp within his presidency and our narrator feels like she has picked the worst fate of all. Both of her parents are dead, and her ex-boyfriend has found himself engaged to someone else.

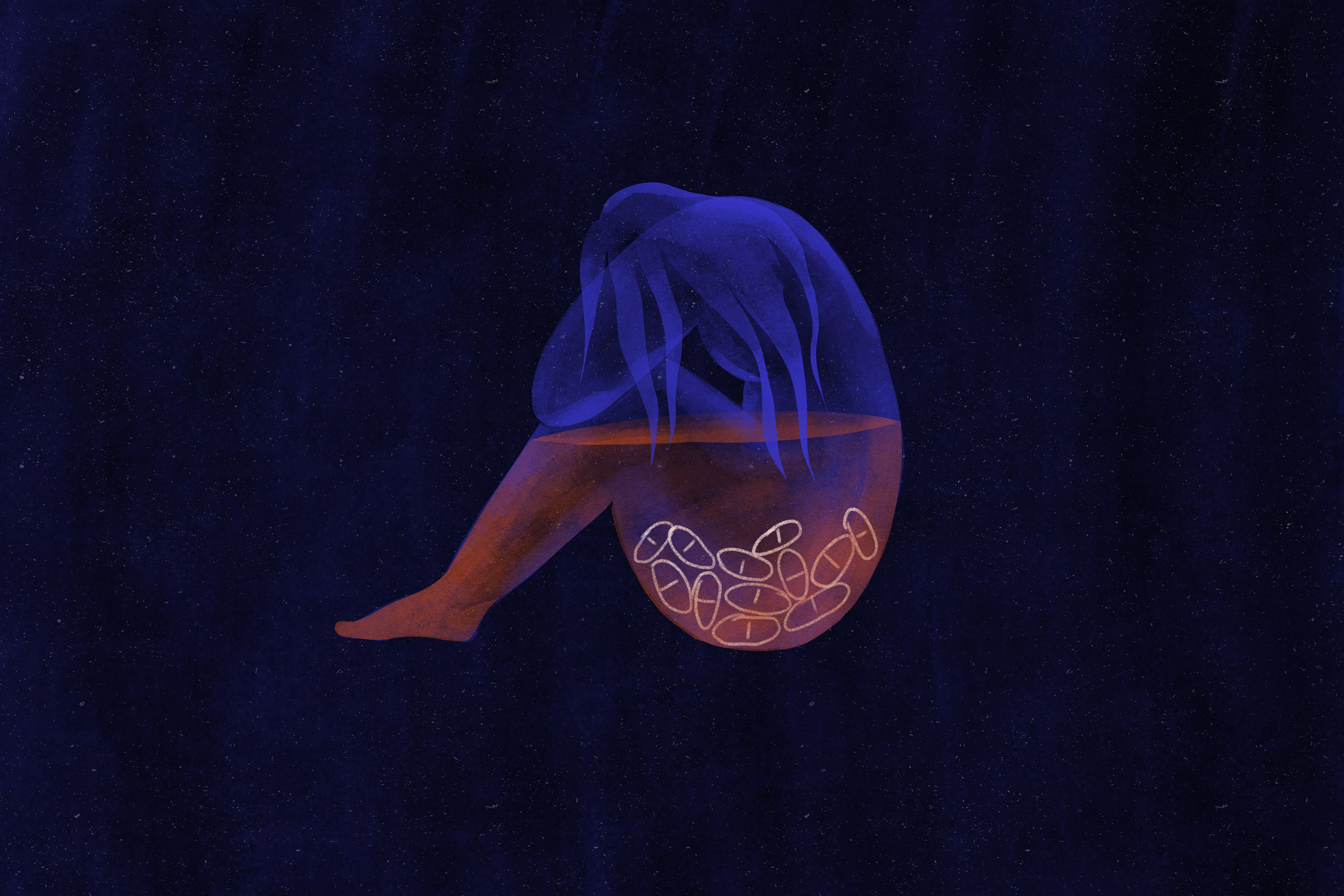

Our unnamed protagonist commits to her anti-social happenings with the help of her psychiatrist, Dr. Tuttle (who she regularly lies to). The narrator begins sleeping most of the day, periodically wandering the city while blacked out on medication, at one point frantically awakening on the Long Island Rail Road.

I often find myself saving screenshots of books that I wish to read, this book being one. It wasn’t until my friend let me borrow her copy that I could finally understand the conversational haze that came from this book. I finished it around the end of September, and since then I have seen a handful of copies in tote bags or purses while riding the A train up and down Manhattan.

Published in 2018, this novel has been at the forefront of many “important books to read in your twenties” listicles. Though the novel is set almost 25 years ago, it still feels current. With political issues rising, and technology expanding if you close your eyes just enough, it would be as if this setting never changed.

The thought of sleeping through the day doesn’t sound all too bad, especially while navigating the state of the world, both then and now. Discussions of depression and being at odds with a friend, all while taking pharmaceuticals sounds like my twenties so far.

With high praise, this book still carries many flaws in my eyes. The unnamed narrator lacks any type of diversity. In her own words, she is “tall and thin and blond and pretty and young” and dislikes nearly everyone and everything. She is not driven by political awakening or artistic ambition. She’s not going to question her privilege, she will just continue to abuse it. “I was born into privilege,” she tells her artist friend Ping Xi. “I am not going to squander that. I’m not a moron.”

She doesn’t seem fond of anyone, and certainly not her best friend or dead parents. She wants to sleep life away because she’s tired of the world as well as her own dull thoughts and “lame memories.” In this case, the protagonist’s view of the world and herself happens to be parallel to their fate. Moshfegh’s sentences are harsh and quick, with few events taking place.

The withdrawn approach is what sticks out when discussing this book. “The notion of my future suddenly snapped into focus: it didn’t exist yet.” With sentences like this, it can be easy to relate to the book since there is such a lack of detail and storyline. The repetitive story finds itself unfolding within itself, which is to be expected when it is a story about nothing. It does not have any crazy twists or turns, which is why it may be seen as frustrating or even boring. The art of doing nothing and fully secluding yourself does take a lot of energy and time, but it seems to work just fine if you have a trust fund.

With a hunger for detachment and dreams, one of my favorite lines of the book was born. Dedicating herself to sleep, our narrator takes the prescribed jumble of pills given by her wacky psychiatrist Dr. Tuttle: “reality detached itself and appeared in my mind as casually as a movie or a dream.” By implanting herself in a coma-like reality she is preparing herself for the 21st century. Moshfegh references this historical period in the narrator’s dreams of planes, smoke, and fire. Both her friends Trevor and Reva work in the World Trade Center, but the lucidity of our narrator’s days makes the audience forget that. Trevor being your everyday finance bro who is trying to hide himself from his impending allegations, and Reva who is a moron who thinks she will change the world with her new diets that are borderlining an entry to a hospital visit.

Along with feeling indifferent about the characters, I question the future emotional effects of this novel and its overall ability to make a lasting impact. Moshfegh set “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” at the beginning of the century before social media and smartphones.

Also, sleep being one of the most discussed topics in the novel has me thinking, do we sleep enough? About 1 in every 3 adults in the United States report that they do not get enough sleep every night. With our faces buried in our screens, our narrator’s project would be hard to pull off in the year 2023, let alone when the book came out in 2018. Not being a good sleeper myself it makes me wonder, why do we not sleep enough. The long days turn into long nights with minutes passing by as each scroll to the next video continues.

I try to not be on my phone before bed, but would I rather be alone with my thoughts or watch an edit that makes my heart sink. As a generation I feel that we are on our phones too much, nor can we make eye contact with one another in a conversation.

As technology grows and expands where does that leave peoples’ social skills? In my opinion, right to the garbage. Instead of having real interactions, people are plagued by the anxieties of rejection and wrongfulness that the art of conversation has been lost.

If I were to commit to this isolation and sleep quest I can similarly view myself as our narrator here. I might just regain a new sense of clarity and understanding of the world around me, but unfortunately, I do not have the time or funds to successfully commit to this process.

One of the most important questions the book asks its audience is: are we living if we do not remember what we did?

The narrator’s motives are not suicidal. “My hibernation was self-preservational,” she says. “I thought that it was going to save my life.” About her sleep, she declares: “If I kept going, I thought, I’d disappear completely, then reappear in some new form. This was my hope. This was the dream.” Despite its faults, this novel still is a thought-provoking piece of work. “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” makes you think, but only after you get past the frustration that comes with it.