James Baldwin was a prolific American author from Harlem, New York. His works are seminal in their open use of gay figures and intimations. As a gay, Black man himself, much of Baldwin’s work is semi-autobiographical: He wrote about the struggles he faced in the mid-20th century due to his sexuality and how those struggles persisted as he took his career overseas. “Giovanni’s Room” is Baldwin’s first novel with a confirmed gay main character, David, whose life shares many parallels with Baldwin’s own. The novel instantly became a classic in the LGBTQ community due to its groundbreaking candor in regard to issues of sexuality. But Baldwin also includes some more subtle feminist lessons in his novel that make it even more powerful.

David is an American expatriate who lives in Paris with the support of his father back home. David’s fiancée, Hella, lives in Spain for most of the book. Although Hella has enough money for the two of them, and it pains David to ask his father to send him money every few months, and he is still unable to bring himself to ask his fiancée for financial support. David’s interactions with Hella are some of the first signs of his difficult relationship with love and his struggles to establish his masculinity.

David has a strict definition of masculinity. It largely comes from his father, who suspects his son might be gay but is too afraid to ask for confirmation. Instead, David’s father continuously asks him to return home to live an all-American life. But even without his father’s urging, David himself feels the societal pressure to live up to the heteronormative expectation of masculinity; 1950s France (as well as the United States) was not very accepting of the LGBTQ community.

These same pressures continue to plague young men across the world today. Male suicide rates are significantly higher than female ones worldwide. This disparity is most often explained by the societal expectation that men should be stolid and hold in their feelings until they boil over. While the statistics are certainly alarming, many men use them to blame women for the general ills of society. Such a line of thought prompts some men to claim male superiority, especially in online communities. Given the hostile discourse surrounding the definition of masculinity, the themes of Baldwin’s novel become increasingly pertinent: “Giovanni’s Room” subtly dismantles the theoretical male supremacy and shifts the reader toward recognizing the negative impact that the search for masculinity can have on women.

Hella is by all indications a loving, caring partner who only wants the best for her fiancé, but she becomes the victim of David’s conflicting emotions. When David meets the young, handsome bartender Giovanni at a luxury bar in downtown Paris, he falls in love; and as Hella counts down the days until she can see her fiancé again, David and Giovanni begin a sexual relationship. Although the novel focuses mainly on the guilt and confusion David feels toward his relationship with Giovanni, any sensible reader is left feeling bad for Hella. In this way, Baldwin expertly keeps the focus on the man’s emotions, as society always does, but makes the woman the story’s true victim.

David’s struggles with masculinity continue throughout the story, primarily driven by his sexual attraction to Giovanni. Yet, his affair with the bartender continues. After each night they spend together, David feels a pang of guilt, but his remorse does not stem from his betrayal of Hella. He makes it clear that he does not love Hella; he can go days without so much as thinking about her, and he even gets frustrated with her for getting in the way of his relationship with Giovanni. David’s guilt stems from his continued relationship with Hella and the love he has for Giovanni, which goes against what his family and society tell him is right.

When Hella ends her trip to Spain prematurely to reunite with her fiancé, David initially dreads their reunion. But, when they finally see each other again, he remembers the feelings he had for her and falls back in love — at least temporarily. In the end, David allows outside pressures, rather than his heart, to influence his decision and picks Hella over Giovanni. When Giovanni dies a violent death, David realizes that his true love is gone for good. Hella sees the hurt in David and finds out he is gay. She leaves David and the book ends with him in his room, all alone.

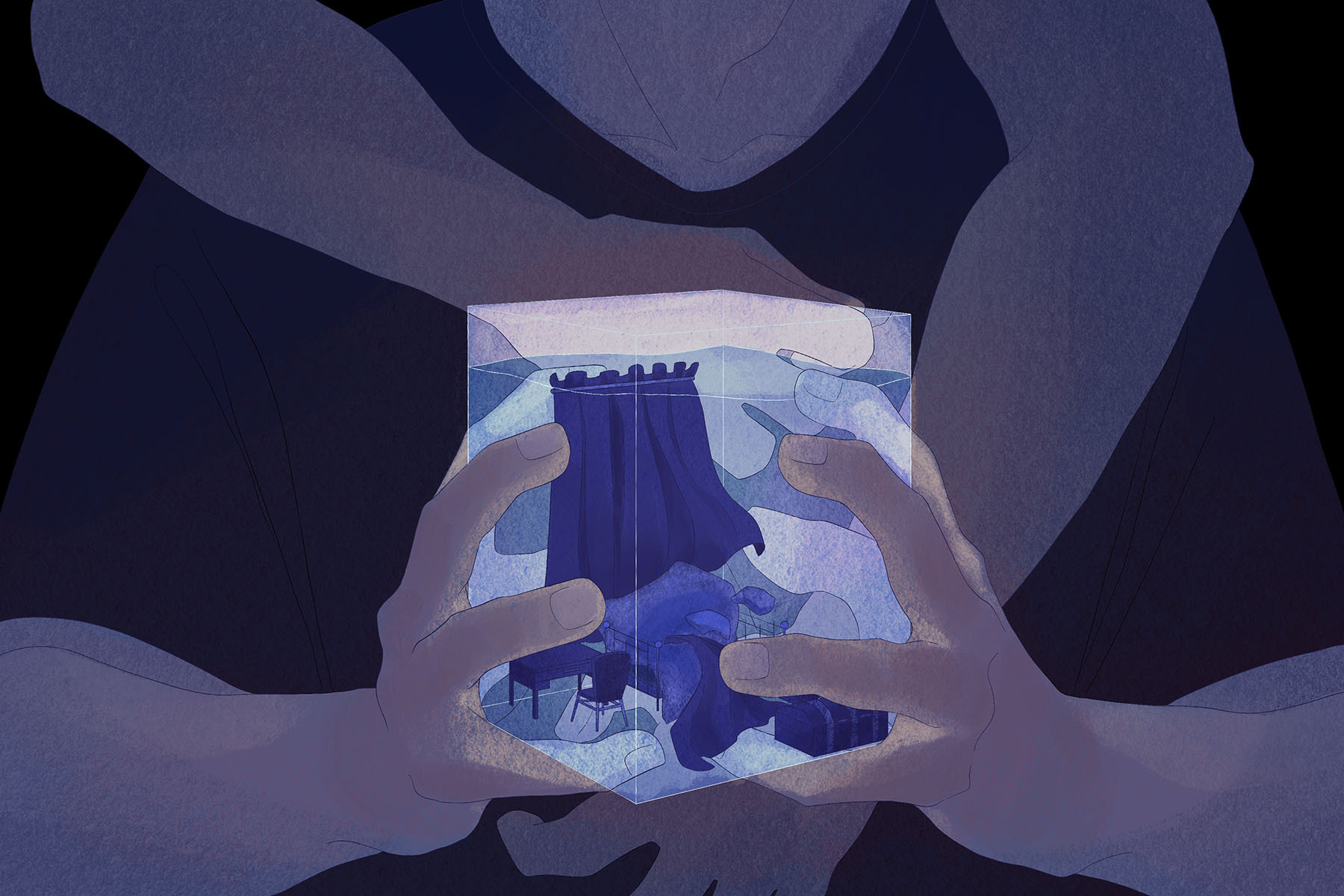

The suppression of sexuality is a persistent theme throughout “Giovanni’s Room.” David feels like he needs to love women, but he is sexually attracted to men. Though Baldwin’s novel is nearly 70 years old, its conflict is ubiquitous even today: Societal rhetoric consistently dismisses the spectrum of sexuality, making it increasingly difficult for members of the LGBTQ community to be comfortable in their own skin.

Nevertheless, “Giovanni’s Room” is not just about gay visibility; Baldwin also appeals to the consequences of toxic masculinity. In recent years, internet culture has emboldened a vocal minority of men who feel wronged by women to speak up about their problems. Other men, who seem to have similar struggles with their sexuality, witness this minority blame their issues on women and follow suit. But their anger is misguided. Men continuously blame women for the problems of society, problems typically caused by other men. The repression of male sexuality and emotion creates a world of rigid masculine standards — despite both masculinity and sexuality being intrinsically flexible. Understanding this dynamic will not only help men in their search for meaning, but it will prevent others from being thrown into the crossfire.