People have changed the way they consume and distribute media since the rise of the internet. Technology is rapidly evolving, and the development and design of social media platforms have made it extremely simple to share digital content — pictures, videos and text — with others. A video intended for a small group of people can easily go viral online in a matter of hours and it may even transcend the original platform in that time.

The Online Etymology Dictionary defines “viral” as “the sense of becoming suddenly widely popular through internet sharing.” First used in this context in 1999, the word was used in the context of marketing and described online phenomena that seemed to bear a resemblance to the spread of a computer virus.

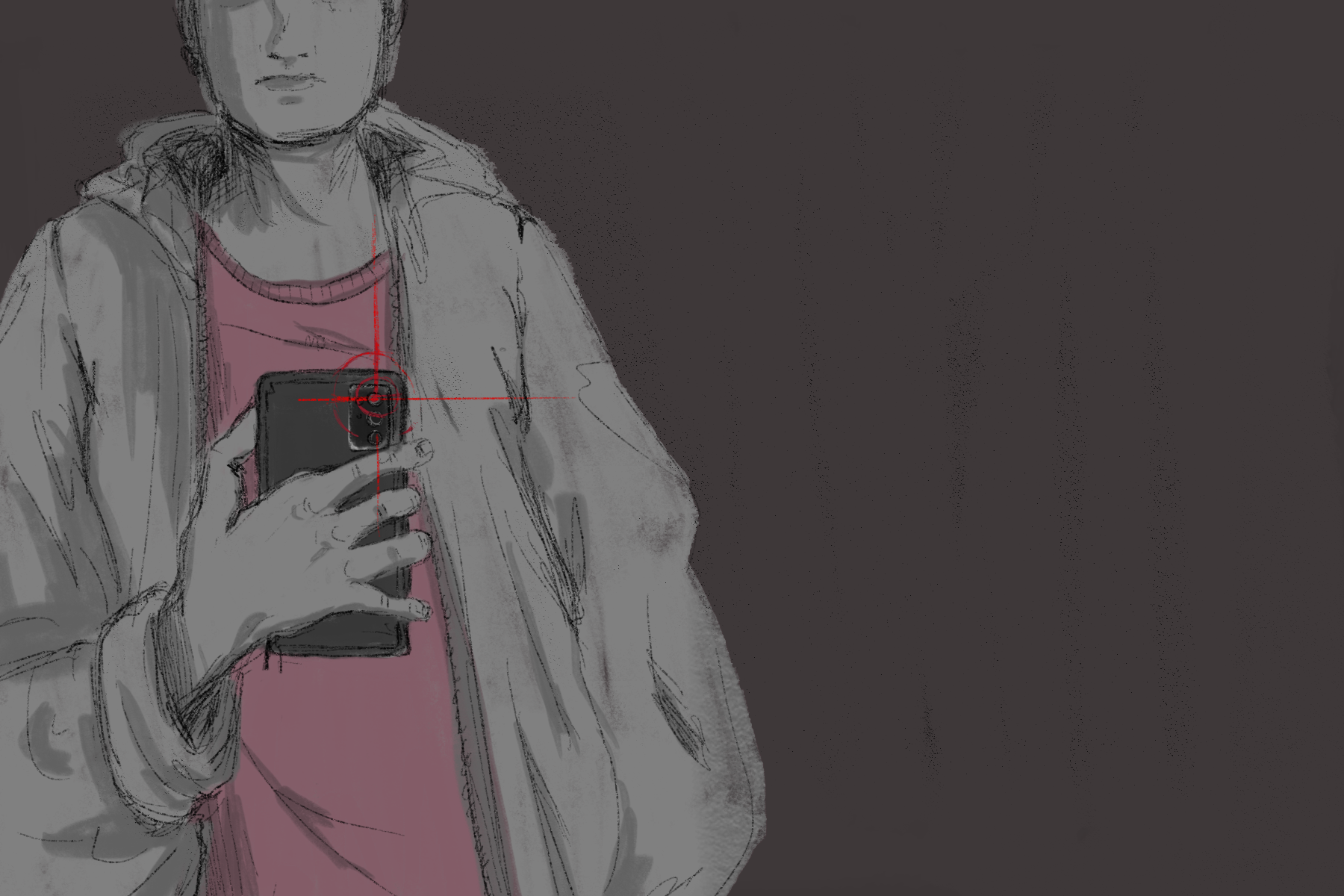

Nowadays, it is quite common to come across pictures or videos of ordinary people doing mundane, funny or even socially unacceptable things (such as this video of a man shaving on the train). Often these videos were filmed without their subjects’ permission and then posted on the internet to elicit a reaction or go viral. Sometimes videos of people clearly having a mental breakdown or suffering from PTSD are described as “acting out.”

These clips are frequently accompanied by captions that fit a specific narrative the audience wants to project on the subject(s). Some of them may be considered harmless or even relatable in some cases, and the intention of the person who recorded and uploaded them may not have been malicious. However, regardless of whether these videos are funny or relatable, these people usually end up being subjected to scrutiny and commentaries based on frequently untrue and exaggerated preconceived notions.

Despite the fact that more than half of the world’s population uses social media, many people are still uncomfortable with their pictures or personal information being available to people outside of their immediate circle. This could be simply to maintain a level of privacy or, in some cases, to protect themselves, especially given the rampant stalker culture fostered by the internet and social media. People should be able to control their online image and presence. Filming without permission and then sharing it online effectively deprives them of their privacy and autonomy. When the world watches or shares these videos on various social media platforms, it’s easy to forget that these are real people with emotions and lives outside of the narratives that millions of viewers have created. They are real people whose lived experiences have been distorted, misinterpreted and misunderstood.

The “random acts of kindness videos,” which have grown in popularity on TikTok over the last year, aptly demonstrate how even basic acts of decency have become commodified in the age of social media. These videos typically receive millions of views. Popular content creators or social media stars participate in this trend by performing unexpected acts of kindness, such as giving flowers to an elderly woman sitting alone, paying for a stranger’s groceries, or giving money to a homeless person.

It’s difficult to tell how genuine some of these acts are when the entire thing is filmed and uploaded to a social media platform where the influencers have a large following. While these actions may have genuinely helped these strangers, it feels patronizing to film people in their supposed “time of need” and post it on the internet, usually without their knowledge or consent. It turns needy individuals into curiosities who will be remembered, dissected and analyzed by random people on the internet forever.

A recipient of one of these “random acts of kindness” complained about how the influencer treated him, saying that it upset him and left him feeling like a desperate person in need of assistance. He had no idea he was being filmed and only found out about the video after family and friends from all over the world began offering him assistance. Other “recipients” who found videos of themselves online have come forward to say they felt dehumanized because these acts were only done for the sake of views and internet stardom. James Hennesy, a tech journalist, perfectly summarizes the situation: “It’s a huge ethical minefield. The idea that we’re being surveilled all the time by people who are just trying to turn our lives into content is something that I think people innately reject.”

Another downside is that these videos are quickly turned into memes or used as reactions in conversations. As these memes spread, they typically take on a life of their own and are used in a variety of contexts that have nothing to do with the subjects. While some people have benefited from the rapid fame gained through these viral moments, for others, things get dark fast. People behind viral memes or videos are frequently subjected to cyberbullying, death threats or plain harassment from strangers on the internet. It has even gotten to the point where their personal information, such as home addresses and bank account numbers, has been leaked online.

This is becoming a more serious problem, and social media platforms have begun to implement policies to address it. Twitter announced in November 2021 that it would revise its privacy policy to prohibit the sharing of photos and videos of people without their consent as part of its efforts to align its safety policies with human rights standards. Facebook and Instagram have similar policies, but most of the time their responses are automated, making it nearly impossible to have these photos or videos removed. Although these measures are absolutely necessary and a step in the right direction, it should be common courtesy for people not to film strangers and then share the footage online without their consent.

In some cases, filming without explicit consent may be advantageous or beneficial. Videos of public servants’ misconduct or people experiencing various forms of injustice can be used as evidence. Another plausible scenario is when the person being videotaped is clearly committing a crime. Furthermore, street photography and videography can play an important role in documenting seemingly historically insignificant events that will be useful in the future. The baseline is that these videos are rarely made with the sole purpose of going viral and profiting from people’s flaws and vulnerabilities.

It’s important to remember that, for the most part, the internet is forever. People who have been filmed and posted without their consent frequently lack the ability to permanently remove the videos. The incredible rate at which images and videos are shared on social media also makes this extremely difficult. It’s also worth noting that making it common practice to film and share digital media of strangers online is unintentionally contributing to the rise of mass surveillance states. Susan Sontag makes a powerful statement in her book “On Photography” that is worth remembering at all times: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s mortality, vulnerability, and mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

While laws vary by country, the general consensus is that filming other people in public places is not illegal. Recording is technically legal as long as the person is in an area where they do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy, such as on the street or on the train. However, just because something is legal does not mean it is ethical, and people’s privacy and autonomy must always be respected. Empathy is always important. While it may be tempting to record people, whether to elicit comments from a large social media following or simply to share with a friend, you should put yourself in the position of the people being recorded and consider how it would feel if you were the one on the receiving end.