The script is written. The set is built. The costumes are designed. The music is composed. All that remains is casting the perfect lead. Every director envisions their ideal cast, but budget limitations, creative differences and contractual conflicts all prevent dreams from becoming reality. With advances in CGI technology, however, directors are no longer limited by a once immovable barrier — death.

As directors Anton Ernst and Tati Golykh began scouting for their film “Finding Jack,” an adaptation of a Gareth Crocker novel, they knew much needed to be considered. The emotional film follows the relationship of a Vietnam War soldier and his war dog, and features a secondary character, Rogan, who “has some extremely complex character arcs” according to Ernst. After months of intense searching, the directors finally decided none other than James Dean could pull off Rogan’s character. The posthumous casting of Dean, who died in 1955, sparked a new wave of debate regarding the ethicality of re-creating images of deceased actors.

“I’m sure he’d be thrilled,” tweeted Chris Evans of “Avengers.” “This is awful. Maybe we can get a computer to paint us a new Picasso. Or write a couple new John Lennon tunes. The complete lack of understanding here is shameful.”

https://twitter.com/ChrisEvans/status/1192137540842733568

Evans takes issues with the authenticity of casting an actor whose actual emotions and mannerisms are computer generated. Using old footage and photos, Dean’s image will be reconstructed with full-body CGI and a sound-alike voice actor. The ethical question implied here is one posed by British philosopher Thomas Hobbes in the Ship of Theseus paradox: If one replaces every part of Theseus’ ship, can it still be considered the original ship of the Greek hero? Similarly, can Ernst and Golykh purport to casting James Dean when his body and voice are mere artificial simulations?

Other critics question if using CGI technology to cast deceased actors opens opportunities to more unsavory recreations: “It’s bad taste & a bad call,” Zelda Williams, daughter of the late Robin Williams, tweeted in response to Dean’s casting. “What’s to stop a pharma from resurrecting Chaplin to sell pills, or casting Bacall in a bad action flick? A famous bombshell back for porn? If all it takes is money & a distant relative’s permission, the future is GRIM and full of corporate ghosts.”

https://twitter.com/zeldawilliams/status/1192231727843799042

One might belittle Williams’ concerns as exaggerated or conspiratorial, but her fears came to fruition decades ago. Ten years after one of Hollywood’s most iconic dancers died, the vacuum company Dirt Devil featured him in their Super Bowl XXXI ad. Viewers praised the ad for commemorating Fred Astaire as he spun around the room twirling the latest household appliance. Dirt Devil acted on permission from Astaire’s daughter to use his image, but Astaire’s widow protested. Her claims that Dirt Devil exploited her husband’s image for grotesque commercial gain led to the 1999 Astaire Bill denying companies the right to use a deceased person’s image unless all rights holders consent.

But what happens when a company unaffiliated with the deceased person’s foundation or family holds image rights? CMG Worldwide and Observe Media merged to create Worldwide XR, which currently holds the rights to the images of over 400 deceased celebrities, including James Dean. Directors are then not legally obligated to seek permission from, or even inform, his family regarding the use of his image. Legality, however, becomes murky when one considers many families of deceased celebrities sold image rights long before CGI technology, when image rights consisted of photos, movies and other paraphernalia of an actor’s previous work — not a complete recreation of their person.

Although Ernst and Golykh’s production company Magic City Films received support from Dean’s family, who view “Finding Jack” as Dean’s fourth movie, not every project will treat a celebrity’s likeness with such respect. As Williams noted in her tweet, businesses can easily, and legally, exploit a deceased celebrity’s image for profit. And if their image is owned by a company like Worldwide XR, the family’s consent is unnecessary.

Peter Martin, the founder and CEO of V.A.L.I.S. Studios collaborating on Dean’s digital development, predicts illegal use of celebrity images becoming a prominent issue. With patience and computer skills, anyone can use CGI technology to produce an underground movie starring A-list actors — living or dead. Others, such as John Knoll, dismiss Martin’s slippery slope argument as implausible given the monetary costs and labor-intensity of CGI reincarnation.

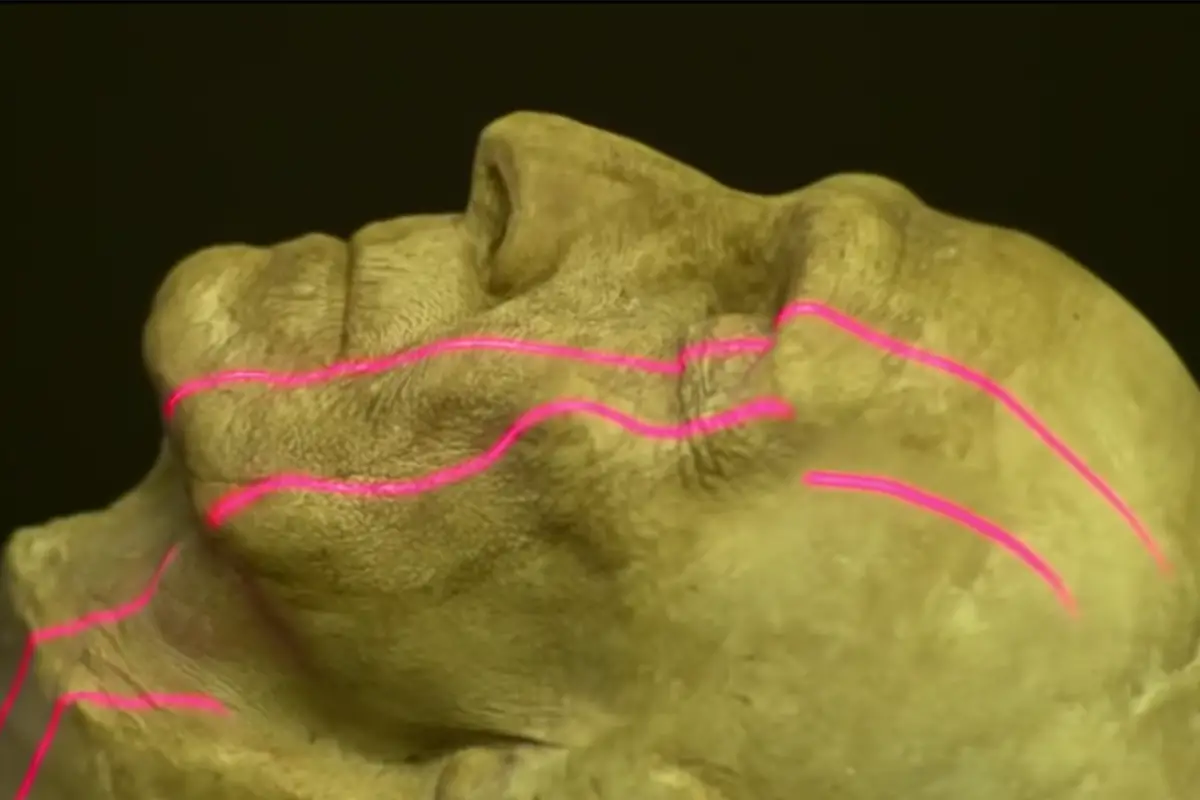

As visual effects supervisor on “Rogue One: A Star Wars Story,” Knoll responded to a mass of criticism regarding the film’s computer generation of Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin. The impressive resemblance of Cushing’s digital doppelganger to the late actor certainly warrants praise for the film’s visual effects and computer graphics team. But the question remains as to why Cushing needed to be used at all. Actresses Caroline Blakiston and Genevieve O’Reilly each portray rebel leader Mon Mothma in “Episode III: Revenge of the Sith” and in “Rogue One,” respectively, and actor Wayne Pygram successfully replaced Cushing as Tarkin in a “Revenge of The Sith” cameo.

Being able to bypass living actors for deceased ones poses a major obstacle to current actors attempting to land roles. “Right now, you’ve got the ‘Fresh Prince of Bel Air’-level Will Smith available for work again,” Martin, referring to Smith’s de-aging in “Gemini Man,” told The Observer. “He can be playing age appropriate roles and be playing younger roles at the same time.”

Instead of auditioning new faces for their commercials, Galaxy Chocolate, Dior and Johnnie Walker reproduced Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe, Grace Kelly, Marlene Dietrich and Bruce Lee to promote their products. But who knows if the famously slim Hepburn would endorse a candy bar? Or if Lee, who abstained from alcohol, would have agreed to promote scotch? Using a deceased actor’s image, even with proper consent, always leaves ethical shades of gray. Which is part of the appeal for many companies as the dead cannot protest.

Actors may struggle navigating the new audition field, but they are becoming increasingly aware of their image rights and the implications of CGI technology. The late Robin Williams, for example, forbade the use of his image for any reason in the 25 years following his death. The Observer notes how living actors will likely be obligated to stipulate in contracts how, when and why their image is to be used after the project’s completion.

Audiences and creators alike must also learn to grapple with the realities of CGI and ask themselves how far ethical boundaries ought to be pushed for entertainment purposes: “Digital technology is clearly reaching a point where photo-realistic depictions are possible,” writes New Atlas, “and we need to ask ourselves what the entertainment of the future will look like? Are we comfortable using the visages of dead celebrities as puppets in our future movies and commercials? Maybe we are.”