What did school look like before tech? I barely remember it. Sometime in middle school, our screechy chalkboards were replaced by whiteboards, and people started to boast their cellphones: shiny pink chassis, black-and-white Nokias. Smartphones came into existence at some point around early high school — though it was only years later that the Conduct Code forbade them, a late reaction to the phenomenon of Facebook Messenger cheating. By the time I graduated, the whiteboards were rendered useless by multimedia projectors, which became a common and necessary fixture of every classroom.

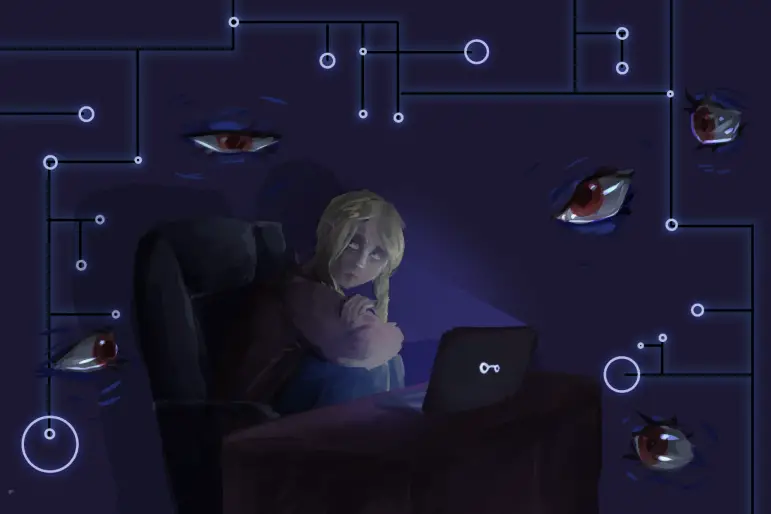

I have lived through these changes; the tightening entwinement of tech and education should feel as natural as the flow of the ocean. And yet sometimes the waves startle me. When I hear middle school students are being given their own Chromebooks, which come with pre-installed software that allows administrators to surveil students’ actions even after school, the thought seems ridiculous to me.

And yet it is true: It’s a million-dollar idea. It’s called GoGuardian, and it’s an American educational technology company that provides Chromebook filtering, monitoring and management. It is designed to prohibit students from accessing certain websites on school-owned and personally-owned devices, though it also allows teachers to view and manipulate students’ screens, and collect information about any activity the student does when logged into their account.

GoGuardian recently reached a valuation of a million dollars, a remarkable yet unsurprising milestone. Though technology played a significant part in the classroom by the time the pandemic hit, the event has accelerated this trend to a previously unthinkable degree. For most students, a year of education would have been lost without access to a laptop. Schools, aware of the situation, were placed with the task of giving their students access to their services while also securing their safety.

What makes the situation particularly interesting is GoGuardian’s definition of “safety.” The software not only blocks an expected list of websites — porn sites, online games and TV streaming platforms — but it also allows schools to identify which students are “at risk of suicide or possible harm to others through threats, violence, and bullying.” It accomplishes this by detecting “searches for guns and bombs, violent acts, bullying, and cyberbullying” in the students’ histories and alerting school officials, who later get into contact with the student to ensure their safety. And these discoveries are not uncommon occurrences: The founders of GoGuardian have said that “across the 2,000 school districts where its software is in use they have heard similar anecdotes dozens of times.”

Despite this, the company has not been free of controversy. Since it allows for such an intense degree of scrutiny, parents and students have stated that GoGuardian “is essentially spyware.” Jessie Rossman, staff attorney with the ACLU of Massachusetts, has also said that while educators are working hard to use new technology to students’ advantage, “this technology need not—and should not—come at the expense of student privacy.”

And Elana Zeide, a research fellow at NYU’s Information Law Institute, has wondered about the psychological effects these kinds of software might have on students: “Are we conditioning children to accept constant monitoring as the normal state of affairs in everyday life?”

Surveillance weighs heavily on the consciousness of the surveilled. Another way to put it: It’s not nice for your (online) school to get all nosy. The online discourse around GoGuardian confirms this as a general attitude: Angelique Richardson, a high school senior at Colonia High School, has called the software “downright disturbing and overpoweringly invasive.” Some others have been even blunter. “STOP HAVING MY DAMNED TEACHER SEE EVERYTHING IM DOING,” one student wrote on Twitter at the company’s account. “LEGIT NO ONE LOVES YOU.”

I certainly don’t love GoGuardian. In fact, my reaction to it upon discovery was disgust. As someone who grew up when the internet seemed little more than an interesting toy, my online habits were loosely, if ever, regulated. This freedom — to research and learn in a world that felt like it belonged exclusively to me — was indescribably valuable. Growing up without access to culture, my desktop computer put me in contact with a world of music, literature and ideas that have made my life richer and that I couldn’t have learned about otherwise.

I know this is a reality for many other students my age: Some friends have spoken to me about the internet as their first gate of access to a deeper understanding of their sexualities and gender identities. Others have told me that the access to content about anti-racism or feminism has not only helped them live at peace with themselves but also contribute to their real-life communities. These kinds of knowledge wouldn’t have been available to them in their immediate material surroundings, nor in an internet heavily censored by parents with different priorities and values.

Still — maybe this is a naively optimistic way to look at the issue. Just as a teenager can stumble upon wonderful knowledge online, they can also stumble upon radicalizing or traumatizing content. Even though I was somewhat internet savvy — I never opened random links, rarely spoke to strangers and refused to share even the smallest personal details — I was still exposed to things that I wish I hadn’t seen when I was so young.

I know that if my parents had understood what the internet was, they wouldn’t have let me explore it alone. Knowing what I know today, I wouldn’t have let myself do so either — and so I’m not sure how to reconcile what the internet has given me with what it has taken away.

It can be useful to look at the tech sphere to understand how similar conflicts are being played out. An example: Proctorio, a monitoring software used to prevent cheating on tests, has been widely criticized for creating “unnecessary anxiety, violat[ing] privacy, and [having] the potential to discriminate against marginalized students.” Though many schools still use the software, some have also moved away from it in recent months, acknowledging that online learning requires new ways to think about education.

Chris Gilliard, a visiting research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center, has said that while a proctoring service might be a straightforward way to deal with the issue of cheating, it is also a way of avoiding rethinking what assessment means or assigning creative work that takes longer to grade.

If test-monitoring software forces us to confront the meaning of evaluation, then software like GoGuardian might be asking humanity a completely new question: What should the relationship between a child and the internet be?