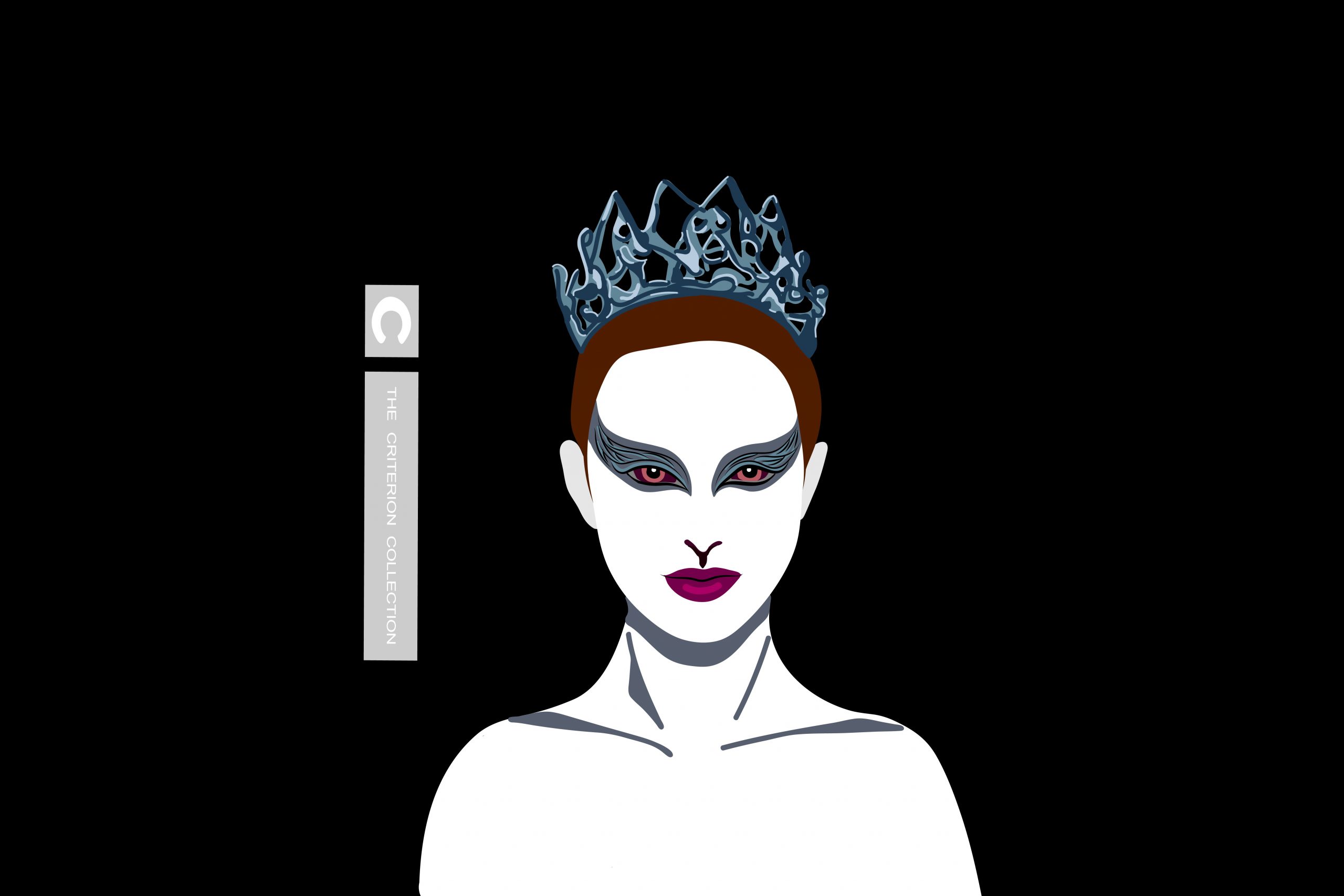

In 2009, the UCLA Film and Television Archive restored Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1948 dance fantasia, “The Red Shoes,” for the esteemed Criterion Collection. The film follows Vicky Page, a young ballerina engaged in a fatal love triangle between her director and the show’s composer, leading to her jump in front of a locomotive. Flash forward just a year later to any cinema in the country, and one can see a similar event unfold: Nina Sayers, a young ballerina, leaps off a staged precipice onto a mattress in the last scene of Darren Aronofsky’s 2010 dance thriller, “Black Swan,” as a self-inflicted stab wound engulfs her tutu.

“I felt it,” she whispers to her director, Tomas Leroy. “I was perfect.”

“Black Swan” received high marks 10 years ago, but the film encountered some obstacles along the way. Although Natalie Portman won an Oscar, its validity was put into question after an uncredited dance-double spoke out. As original as a story about a stressed-out ballerina might be to some, it is part of a longer history of ballet films, in which “The Red Shoes” is perhaps the cornerstone. Additionally, because of its Tchaikovsky-remixed score, it was ineligible for any soundtrack honors come the Academy Awards. So, did it deserve all the hype, or is it simply a shameless Hollywood cash-grab?

Such criticism may be warranted if not for the film’s melodramatic complexity. “Black Swan” may be about ballet, but it does not endorse it. It draws influence from a foreign film only to conjure philosophical discussions of artistic purity. Sex and gender roles play out only to drive Nina’s psychosis. This reflexivity makes the film a metaphysical, cultural as well as political revelation. It isn’t just a dance film, a Hollywood remake or a story of the “tortured artist” archetype; it’s a huge middle finger to a patriarchal, exploitative and racialized industry, and one that should finally earn its renown as an important contemporary film.

In many ways, “Black Swan” is a conceptual, visual and audible adaptation of its generic predecessors. Aronofsky has been compared to the Pressburgers in his treatment of ballet, but instead of retracing the steps of “The Red Shoes,” Aronofsky creates a near-parody of that earlier behind-the-scenes romance, twisting the love triangle into sexual misconduct.

At the same time, the director distorts “Swan Lake” by creating motifs out of the least melodious parts of the ballet and remixing them with atonal whispers, screams and chortles. The show’s prologue, a singular piece of music never once repeated, becomes a recurring theme for Nina’s insanity. Aronofsky fights Tchaikovsky and Pressburger for the emotional impact of ballet, opting for horror instead of spectacle.

A similar self-awareness may be said in regards to the film’s dependence on Satoshi Kon’s 1997 anime, “Perfect Blue,” and not just when it comes to plot or cinematography; replacing Kon’s tutu-touting pop star Mima with Nina, pretty ballerina, “Swan” glimmers with shades of “Blue” on the most basic of levels. Even the dialogue references the anime’s title. Part of this blunt homage is due to the fact that Aronofsky acquired the rights to adapt “Perfect Blue” for American audiences while recreating a scene in the anime for “Requiem for a Dream.” So, in a sense, the director could very well have remade Kon’s work directly, but instead he forces us to question what a remake entails and where the line between novelty and reinvention is drawn.

Aronofsky’s pasticcio of both films garnishes the stage not with crimson curtains and dazzling sets, but with long shadows and black mirrors. As an intersectional and flamboyant participant in Hollywood’s creative bankruptcy, “Black Swan” becomes reflexive on the concept of adaptation as a style in itself.

Beyond this theoretical dissection of the film’s stylistic merits, “Black Swan” also comments substantially on what it means to be a woman in the workplace. Nina is sexually manipulated throughout the film, providing the movie’s central conflict. Yet near the halfway point, Lily infers that something happened between Nina and Leroy, but doesn’t suggest Nina report the director for misconduct. Instead, she says, “Someone’s hot for teacher.” As a result of her rival’s dismissive attitude, Nina begins having disturbing visions of Lily, both real and imaginary, often as Leroy’s new mistress. It creates this false dilemma for Nina to appeal sexually to her superior, as if that is the gateway to success.

Unfortunately, this is true for far too many women and men across the country. The myriad experiences of female entertainers in particular, the ways in which it is swept under the rug as it is for Nina, have evaded popular discussion until recent years. “Black Swan” may offer an exaggeration of what happens in the dance world in particular, but when a film like last year’s “The Assistant” tries to explore the perils of being a woman in entertainment, but ultimately casts the issue into oblivion through extreme minimalism, a melodramatic thriller seems a more effective alternative to get the same point across: Women face mental and physical dangers in the workplace.

As conspicuous as the heterosexual tensions are in the film, there is also evident homophobia pervasive in Nina’s company; fellow dancers laugh at Nina for staring at women, as if she’s “obsessed,” and Lily gaslights Nina after having sex by implying the latter had a “lezzy wet dream.” It all amounts to an institution that denies its sexual undertones, with Nina selected as its preeminent martyr as a virginal white youth. It’s a #MeToo film before #MeToo entered the mainstream and simultaneously one that explores the struggles of gender nonconformity in a world populated by identical bodies and faces.

One cannot discuss the film’s exploration of the doppelganger without understanding who is being reflected: a white woman. Yes, the title of the film solely refers to Tchaikovsky’s feisty waterfowl, but the film, in its emphasis on the dichotomy of colors, also welcomes a race-based analysis. Nearly everyone in the film is white; in a company of several dozen, there are only three people of color: a Black man, an Asian woman and a Black administrator whose face we barely see. Aside from one or two extras, the overwhelming majority of the cast is white.

This isn’t Aronofsky being a racist per se; ballet has been and unfortunately remains very white. For every Misty Copeland there are countless women with the skin and figure of Portman, and the film’s use of digital face-swapping to illustrate Nina’s psychosis brings this fact to the fore. The homosociality of ballet, adjunct its homoeroticism, is coupled with a homo-raciality that makes it look like a sexual cult through Nina’s eyes, a world that breeds delusion and uses young beauty to perpetuate a peculiar manifestation of white supremacy.

Aronofsky challenges the sustainability of this world with a character who is at once exactly what the industry desires but also resistant to the conformity pressed upon her. She is both model and detractor, a product of the system as well as a martyr for its downfall. Nina adapts through a narrative that is in itself an adaptation, a metamorphosis within metamorphosis. One could even view the body-horror aspects of the film, as Nina pulls feathers from her back, as analogous to a sort of transphobia. Yes, in terms of sex, though not necessarily contingent on the gender binary, and also just in general. Change is scary, regardless of its form.

Outside of the mise-en-scène, Portman transforms herself into a dancer but is ultimately seen as a fraud; she is not a professional dancer, and the film seems aware of this in its exploration of imposter syndrome. As the film surrounds this complicated protagonist, so too does the viewer, and from her unique perspective Aronofsky hooks the viewer with a hyperbolic look into the world of ballet and takes a nose dive into horror in the final quarter.

“Black Swan” is a film that touts the importance of color with a conspicuously white cast. It’s a project that explores the multiple implications of its title and references past films only to divert expectations. Ballet may not be filled with identical clones or murderous jealousy, but the presentation of such sensationalism reveals more about our culture than could a more original and restrained picture. For all of its melodrama, “Black Swan” remains a nuanced, self-conscious production that could very well see itself acknowledged as a fascinating piece of post-modern cinema.