Intersectional is a term that gets thrown around frequently, often without a good definition. There is a tendency to oversimplify it by treating it as a literal intersection — as two or more separate pieces overlapping one other — when in reality, it creates a wholly separate identity. Coined by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, the term evolved in part from the legal case DeGraffenreid v. General Motors, where Black women experienced discrimination because of their race and gender simultaneously.

The Black women bringing the suit were ultimately dismissed because of the court’s refusal to bind gender and race: White women were employed in secretarial jobs and Black men were employed as factory workers and, by that logic, there was no discrimination, even though Black women were being actively discriminated against. Just over 30 years after Crenshaw coined the term in 1989, intersectionality allows for the discussion of many complex issues, such as Teyana Taylor being crowned as Maxim’s “Sexiest Woman Alive.”

Historically and currently, Black women’s sexuality has been and is used as a weapon against them. Megan Thee Stallion and Cardi B’s song “WAP” drew ire and concern from many, Jordyn Woods received extreme backlash for her alleged affair with Tristan Thompson, Rihanna was met with just as much victim-blaming as sympathy when Chris Brown abused her, Janet Jackson’s unfortunate costume malfunction at the hands of Justin Timberlake virtually ended her career while aiding his — the list of abuses goes on, all the way back to the prima donna character in blackface minstrel shows. But it’s especially sinister since, just as often as Black women are hypersexualized, they are regularly masculinized and proclaimed undesirable.

The infamous racist cartoon of Serena Williams comes to mind, as does the awful body shaming of Michelle Obama, the concerning treatment of Black women on dating apps and the Mammy and Funny Old Gal blackface characters. Each of these figures were both desexed and made fun of for their appearances. In fact, the female characters in minstrel shows, even the hypersexualized prima donna, were always played by white men.

The weight of this history and present means that sexuality is not simple for Black women. Maxim would like us to pretend that it is.

As of 2016, Maxim has done us all the great favor of eliminating the numbered ranking system from their Hot 100 list and as of 2019, they’ve started including fun keywords like “entrepreneur” in an attempt to repackage their list as an empowerment tool. In fact, the article on Taylor is full of little flairs to that effect.

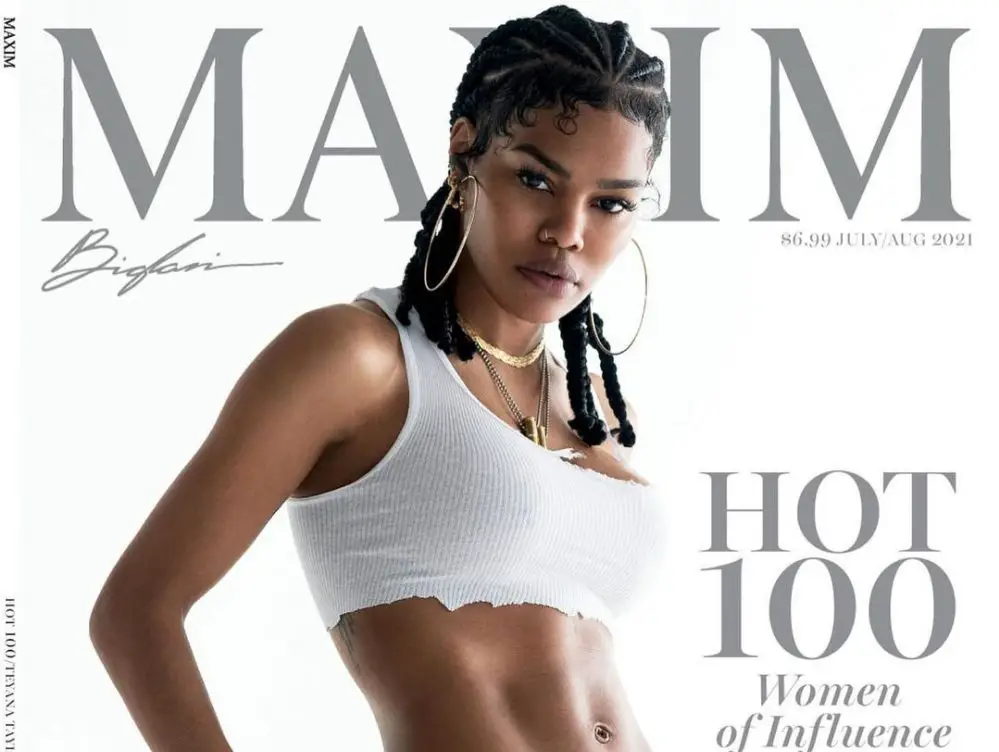

While the piece preambles with Taylor’s accomplishments, it ultimately reminds readers of the reason they’re here: “A graceful choreographer-dancer, actor-director and top ten recording star, she has brains, talent and, well, the photos show the rest.” The article places Taylor’s brief quotes about her life and goals alongside photos of her in various stages of dress. The writing and presentation of her thoughts may claim to be focused on more than just her appearance, but the article tags are illuminating, with “sexy” coming second and Taylor’s own name listed last.

The article itself is one thing. If the dominant culture in America did not insist Black women’s bodies were not their own, maybe Taylor could be crowned with minimal controversy from all parties as just another entertainment blip. Obviously, however, that is not the case. Taylor is Maxim’s first and only Black woman to be named “Sexiest Woman Alive” in 20 years of publishing their list.

Meanwhile, Black women experience sexual violence at a much higher rate than their white counterparts. 1 in 4 are sexually abused before the age of 18 and 1 in 5 are survivors of rape. Between 40% and 60% of Black women report experiencing coercive sexual contact by the age of 18 and 40% of confirmed sex traffic survivors in the U.S. are Black despite only making up 13.4% of the population. Maxim is worlds beyond existing in a vacuum.

Taylor’s crowning has generated buzz. The response is mixed; a Metro article title captures one reaction extremely well: “Teyana Taylor is Maxim’s first Black sexiest woman after 21 years — what took so long?” Alternatively, Tony, a random Twitter user, makes the dismissive case that “There’s hotter IG models.”

There’s no easy answer about what to do with Taylor’s win. It seems clear that it should not be blindly celebrated, but it’s also hard to deal with absolutes about its repercussions. As feminism has become a commodity and Black women’s features are torn from them and worn as costumes for profit, what is the best escape route? Is it assimilation? A collective blend into a society that saves some of its worst vitriol for those born into this particular melted oppression of gender and race? One hopes not. While we can all marvel at Taylor’s gorgeous washboard abs and alluring brown eyes, we can also recognize the issues currently present in our society and work to fix them.