For many people across the globe, social media seems to carry a bad reputation as a tool used for sharing misinformed political information and openly allowing “slacktivism” to thrive. However, since the inception of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2016, activism’s presence on social media appears to have grown from a purposeless, stagnant attempt at collective change to a movement driven by deep roots and organized, real action.

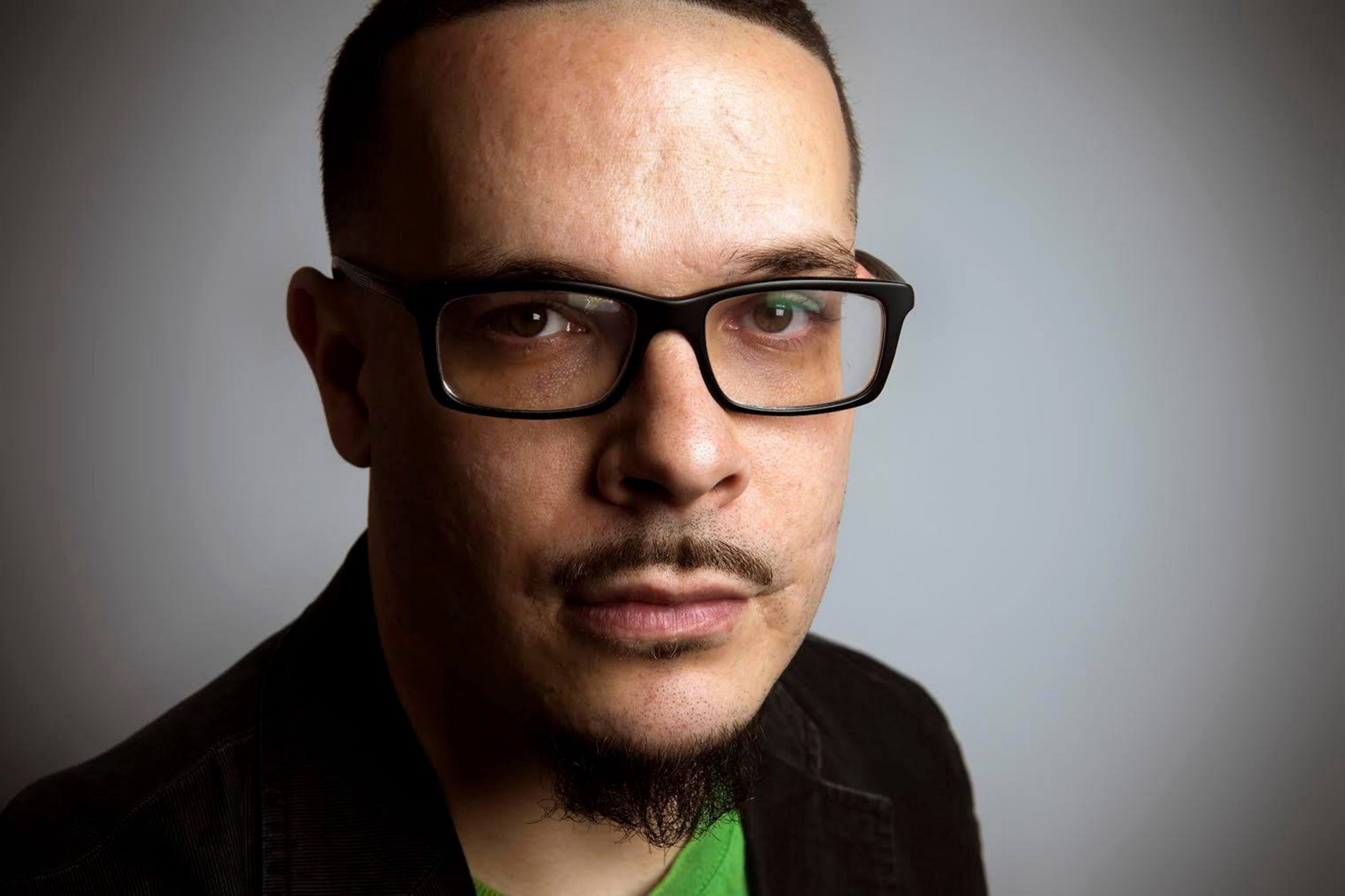

At the forefront of this phenomenon is journalist, writer and activist Shaun King, whose presence on social media has boosted social issues, such as police brutality and hate crime violence, straight into the public eye. After starting multiple different charity fundraising sites like aHomeinHaiti.org, TwitChange.com and HopeMob.org, King gained prominence after the hugely controversial shooting of black teenager Michael Brown. Sharing the opinion of many protesters, King argued in an article that police officer Darren Wilson was not in any life-threatening danger, and that the shooting was racially charged.

The shooting of Michael Brown not only brought awareness to King’s work, but it also awoke a new sense of passion in people’s hearts. Up to this point, activism on social media was largely passive. People placed overlays of tragedy-stricken countries on their Facebook profile pictures and shared news articles about “saving the children,” but no one ever really took these online grievances into the stratosphere of genuine, real-life human involvement. Instead, before King and the #BlackLivesMatter movement stirred activism from its complacent position behind a computer, much of social media justice remained ineffective.

Activism was docile, hardly garnering any true action from the people who claimed to be a part of it online. More so, the case became that these online participants only wanted to prove that they cared about the traumatic events occurring right before their eyes, and whole-heartedly believed that changing their Facebook cover photo to a LGBT pride flag held real merit.

This form of activism, or slacktivism, plagued social media for several years. Notable examples include 2011’s Occupy Wall Street movement and Kony 2012. While Occupy — a Twitter-organized protest and subsequent international movement aimed at bringing awareness to economic inequality — wasn’t a complete failure, it never gained the velocity that activism groups of the later 2010s achieved.

Kony, on the other hand, emananted the core problems of slacktivism to a T. While the viral video about Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony did a terrific job at stirring up the masses and getting each and everybody’s attention — the video was even played in one of my middle school classes — it ultimately failed at bringing people together enough to organize any actual change. People were upset, but only ever in the “Oh, that’s a shame” sense.

This kind of meaningless online awareness lasted for multiple years, up until 2016’s Black Lives Matter movement — named after a 2013 tweet in regard to Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman — rocked the country. After the fatal shooting of Brown and the subsequent acquittal of officer Darren Wilson, angry and impassioned people took to the internet to express their pain about race-related injustices.

Since its first use, the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter has been tweeted 30 million times, around 17,002 times a day, according to Pew Research. The popularity of this phrase and the power behind it led to well-organized marches and protests that brought the issue of police brutality to national media attention.

This #BlackLivesMatter activist wants to take her message from the streets to Oakland's city hall. pic.twitter.com/AWcZcexRjH

— AJ+ (@ajplus) August 2, 2018

#BlackLivesMatter will counter-protest 'White Civil Rights Rally' in DC scheduled on anniversary of deadly #Charlottesville rally: https://t.co/7IfYG2rjWZ pic.twitter.com/B82gWDMpQL

— The Root (@TheRoot) July 30, 2018

You might ask, “What makes Black Lives Matter different from movements like Occupy Wall Street and Kony 2012?” The answer lies in the personal connection between the movement and its supporters. Whereas previous attempts at online social advocacy asked people to care about issues that were often far away from them, Black Lives Matter articulated a problem felt by its supporters every day of their lives. The creators and supporters of the movement weren’t trying to change something that didn’t affect them directly; instead, engagement in Black Lives Matter meant bringing change into their own lives.

The personal frustration that propelled, and continues to propel Black Lives Matter, is the same kind of frustration that has brought popular involvement to the Women’s March, the #MeToo movement, the Climate March and the March for Our Lives — to name a few. Social media is used primarily to express and communicate personal attitudes and feelings about subjects that affect users in their daily lives.

The before-mentioned movements were all organized primarily through social media, and are most talked about through social media as well. Why? Because these issues are personal, they are no longer unavoidable. Whereas disingenuous motivation seemed to be at the root of online social change in the past, people today are more eager to connect and team-up with those that share their worries. People will go to great lengths to make their opinions about injustices known.

This is where people like Shaun King come in. Although many journalists and activists have gone to the internet to bring light to important issues plaguing the country, King’s entire platform has its feet planted in social media and how it can be used for more good than one might think.

Having followed King on Instagram for a while now, I can say that he posts almost daily about under-reported crimes and events in an effort to bring immediate action to the subject. King does not simply report on what has happened, but rather urges his followers — and there are many — to help him bring justice to a particular case. King uses social media for its greatest use: as a way to spread the word and, in turn, receive answers.

For instance, in 2017 he organized an online social media campaign to find the perpetrators behind the assault on DeAndre Harris during the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. The Washington Post credited King with the identification of three of the men behind the assault: Daniel P. Borden, Alex Michael Ramos and Jacob Scott Goodwin. King’s actions were a prime example of how social media can be used to organize the people and provide real justice.

King doesn’t just present the problems, he uses his various online platforms to actively try to solve them. While for some time it seemed that activism online was falling ill to dying movements and artificial compassion, a reinvigorated activist-renaissance has now found its home in the personal lives of the people it affects, both online and out in the streets.