The word “literature” comes with certain connotations — it’s associated with being long, hard to understand and is sometimes thought of as being outdated. While works by the likes of Shakespeare and others have been the subject of debates regarding their relevance and accessibility, the argument that keeps these texts alive often involves their ability to transcend time and portray the human condition. However, what if there was a kind of literature that was short and simple, with language that wasn’t so difficult to understand? Not only that, but it could also be played as a card game? All of this can be found in “karuta,” specifically, “Uta-garuta,” which translates to “poetry karuta.”

Karuta is a card game (“Karuta” literally refers to the cards used to play) that has many variations, but for the sake of this article, I’ll be discussing the most popular form of Karuta, competitive “Uta-garuta,” which uses the “Ogura Hyakunin Isshu,” a collection of 100 waka poems, each written by a different renowned Japanese poet. Waka poems are defined by their simplicity, basic form and readability in the original Japanese..

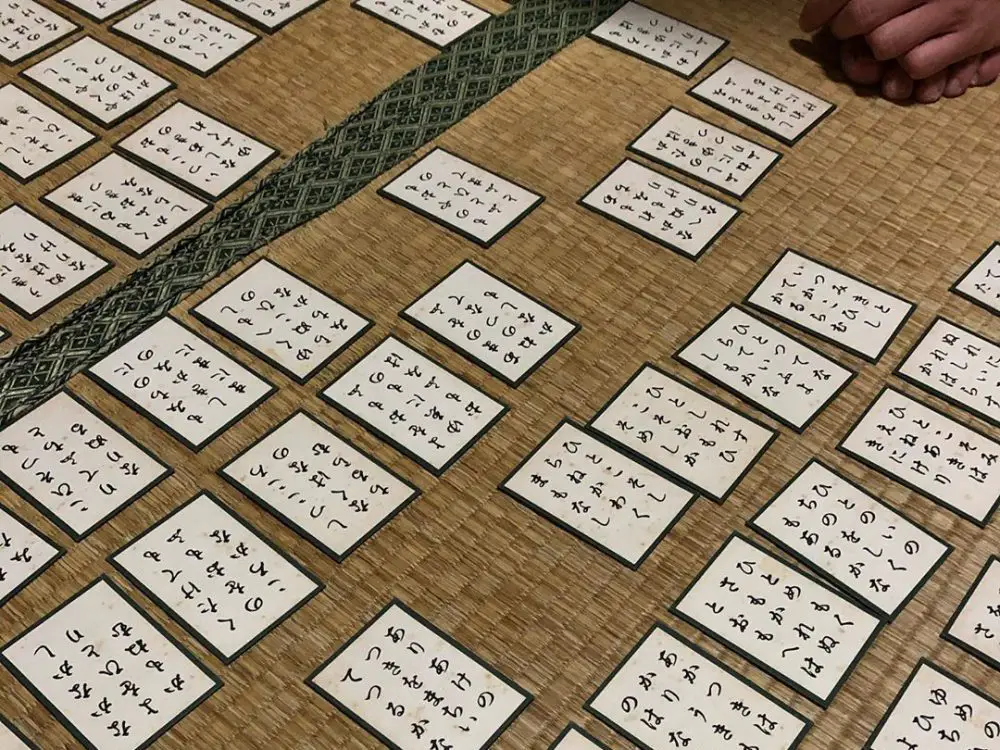

The game uses 200 cards that each feature a part of a poem from the Hyakunin Isshu. The 100 poems are split into two as each card contains half of one poem. The half of the 200-card deck that contains the first part of each poem are used for reading. They’re read out by someone who is not playing, and in official competitive karuta matches, readers must be certified to ensure their rhythm and intonation are correct.

The second half of the poems are on the playing cards. Players must have poems memorized so that when the reader reads out the first half of the poem, they can take the corresponding second half. In single matches, where one person plays against another, they compete to see who can take the 25 cards first. Players receive 25 cards each and they’re free to move them during matches, though memorizing their position is key to both players. In team matches, which feature up to five players, a minimum of three players must win 25 cards in their respective matches. As there are only 50 of 100 playing cards on the field, players must be careful not to mistake cards for a “dead card,” one that is not currently in play, or it’s a fault.

The game rules are complicated, with a variety of skill levels and strategies that are played at a competitive level. Players refine their dexterity to take cards with accuracy and speed. Experienced players are often able to take cards within seconds of the first (or first few) syllables being read aloud, and in top-level recorded matches, it’s often difficult to tell which player took the card first. There are a variety of reasons why people could be drawn to the game’s competitive nature. While competitive karuta remains a niche sport in Japan, those who play it tend to be extremely dedicated. Perhaps one of the reasons the game has remained relevant is its poetry.

The Hyakunin Isshu features famous poems from the Nara period to the Kamakura period. They’re about four or five lines each, depending on the translation. The poems revolve around human experiences and will often refer to nature for imagery and metaphors. For example, the first poem in the collection reads, “I sit alone on this autumn night, / In my tumbledown hut with broken eaves; / But it is not just the dripping dew / That wets my sleeves.” The poem is subtle, but with only a few words successfully reveals the loneliness that the writer feels in the middle of the night.

Similarly, the ninth poem reads: “I sit in my room all alone, / Enveloped in endless rain; / Faded like the cherries, / Spending my days in vain.” This poem, too, is subtle but successfully demonstrates the author’s feelings as she compares her youth to a withering cherry blossom. The images that these poems evoke are simple, yet effective.

The Hyakunin Isshu contrasts with classic English literature, which may be complex and require historical context to fully understand. For example, the first few lines of T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” reads: “April is the cruelest month, breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing / Memory and desire, stirring / Dull roots with spring rain.” Not only is the tone more authoritative, but these lines are also better understood if the reader knows that the poet witnessed the seemingly apocalyptic conditions of World War I.

The entire poem is the size of a small book, with intricate words that can be best appreciated by those with a strong foundation in the English language. In contrast, the Hyakunin Isshu’s historical context plays a more supplemental to the poetry. For example, Ono no Komachi, the author of poem No. 9 was known to be very beautiful. This tidbit of information adds some context to her poem on aging; however, it doesn’t require knowledge of Japanese history to understand her sorrow when she compares herself to the fading cherry blossoms.

Not only can karuta be a fun game in itself, but its poems remain relevant because of their simplicity and portrayal of human emotion. Each card can evoke strong images and is relatable to all age groups and genders, even in contemporary society. The complex poetry of Shakespeare, T.S. Eliot and other renowned poets are a valuable resource; however, there is a beauty in the simplicity of the Hyakunin Isshu. While these poems are praised for their double meanings, they can be appreciated at first glance as well. Additionally, Karuta provides a new dimension to appreciating poetry, as it emphasizes the precision needed to distinguish single syllables.

Literature doesn’t need to be complicated to hold value, and Karuta demonstrates that classic poetry, when weaved elegantly and minimally, has the ability to retain its relevance and serve as a valuable source of art for those who are both new and well-versed in the world of literature.