In 2014, after a series of disappointments with traditional publishers while pitching her poems to grander anthologies, Rupi Kaur self-published her debut poetry book, “Milk and Honey.” Just a few months after the work’s release on Amazon’s self-publishing platform, it was picked up by Andrews MacMeel Publishing. “Milk and Honey,” consisting of short, illustrated and Instagram-able poems, quickly became an international phenomenon and No. 1 New York Times’ best-seller, launching the young poetess into fame.

“Milk and Honey” was the first of a series of books featuring Instagram poetry that would go on to flood the literary market and dominate the poetry industry to this day.

This specific genre of poetry, which I classify as Instagram poetry because of its short nature and the fact that many of its authors started off sharing their work on the social platform, has gained a cult-like following. Usually collected in short, cohesive anthologies, Instagram poems are brief, angsty and deeply relatable. Churned out at a speed and quantity that is frankly staggering, these anthologies have made stars out of the likes of Amanda Lovelace, R.H. Sin, Najwa Zebian and, of course, Kaur.

At one point in my life, I was obsessed with these books, devouring one after another at record speeds. I picked up “Milk and Honey” at the age of 14, and it rocked my world. It presented poetry in a way I had never seen it before. It was understandable, pleasant to read and — most importantly — it made me feel like no written verse had ever made me feel. I was not unique in my experience; for thousands of teens across the globe, Instagram poetry made poetry cool again.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BvkvMjEn4Oc/

For the longest time, I tried and failed to explain what had triggered the sudden obsession, but eventually, I moved on to other books and poetry, forgetting all about it. A few weeks back, perturbed by curiosity and an episode of nostalgia, I picked up a Lovelace book and flipped through. I was horrified. Nothing like the deep verses I remembered, the writing struck me as shallow and borderline cringy. Further investigation produced consistent if not worse results.

There’s nothing quite like seeing the heroes of your youth crumble after a shift of perspective. Now, I’m not here to tear down anyone. I don’t take pleasure from pointing fingers and raising my nose at the hard work of others, but the current Instagram poetry trend — as it stands — does more harm than good to the literary genre it claims to inhabit.

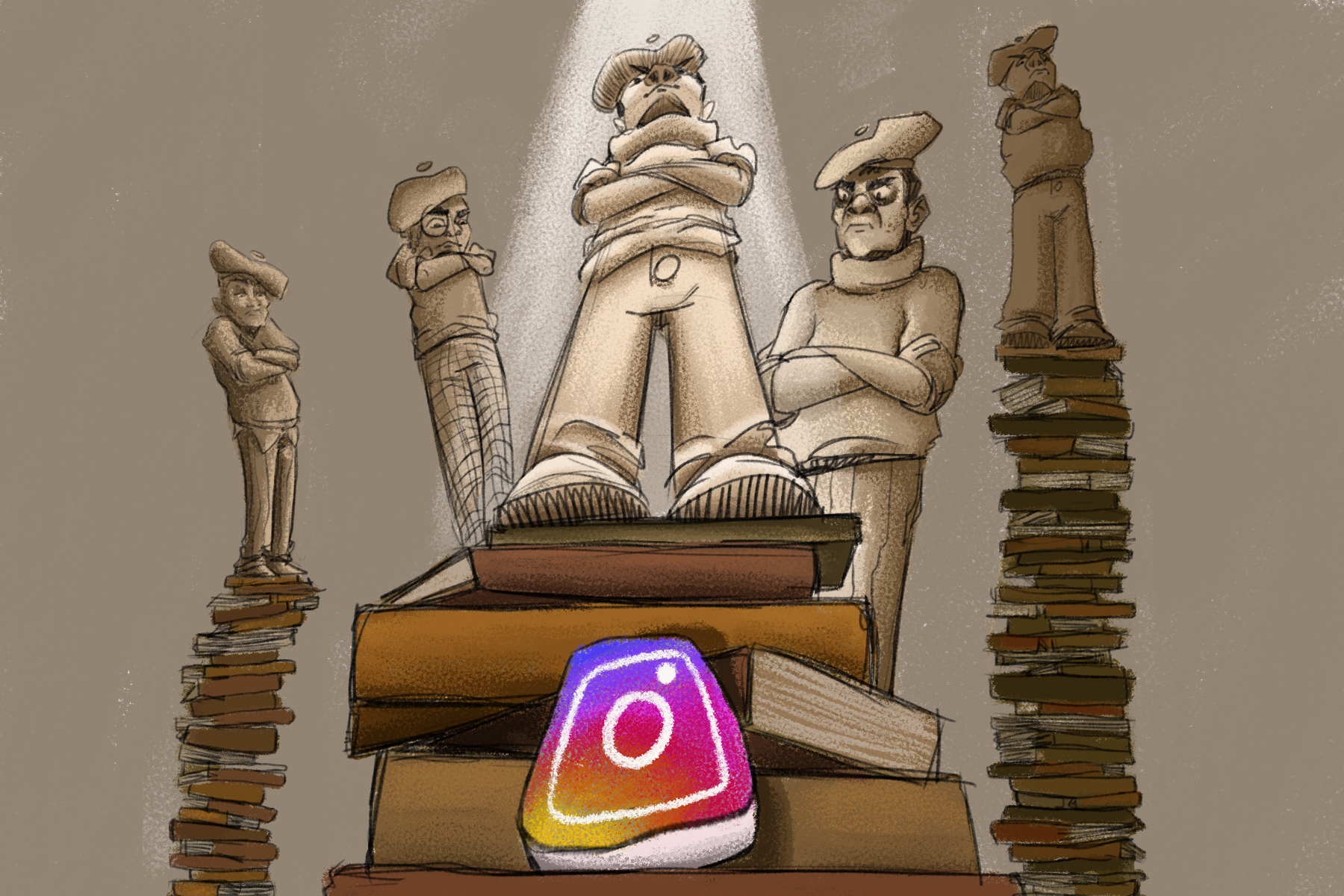

Instagram poetry, while it surfaced with Kaur’s debut, has morphed into a whole different beast, with authors replicating it to varying degrees of success. All reincarnations of her work are published by one publishing house alone: Andrews MacMeel. It may sound like a crazy conspiracy theory, but like a lot of these books, it’s far shallower than that.

Andrews MacMeel Publishing, which up until “Milk and Honey” was known for gag gifts, coloring books and comics, has found another inherently marketable model, and they will continue to produce it until it stops being lucrative. Instagram poetry has made the genre algorithmic, and hence replicable for profit. Yay.

If the algorithm were producing quality work, there would be no bone to pick, but that’s not what’s happening. Poems sometimes only consisting of one line are being mass produced and sold as peak poetry to young audiences. The trend becomes more problematic when all the works are overwhelmingly flat and one-note, reeking of a fake deepness only acceptable as “literature” on Tumblr blogs and, well, Instagram pages.

Admittedly, classic poetry is not the most engaging for young readers. Written in old, convoluted English, the poetry that was once praised as the pinnacle of culture loses its sheen in a modern world. Love poems produced during the same era, once intended to charm women, now read as outdated and in many ways are creepily dominated by the male gaze. Faced with this reality, it’s not hard to see where the appeal of these newer works comes from.

The Instagram poetry movement’s value lies in the fact that it has led to greater representation within the genre of poetry for women, minorities and other diverse voices. It has also made poetry more greatly accessible to younger generations, removing for many the connotation of poetry as a stuffy, boring form of writing.

That being said, it is important to acknowledge that Instagram poetry isn’t highbrow in the least. Just like there are quality young adult novels, there can be quality YA poetry books. However, they do not and should not dictate the direction of an entire genre of writing. To limit what we consider good poetry to Andrews MacMeel publications is to do poetry a disservice.

It’s lazy and disrespectful to let marketability determine the future of such a valuable and historical art form. If poems like Lovelace’s that read “He / won’t / stop / hunting / me” (that’s it, that’s the whole poem!) are what stop poetry from going extinct, then so be it, but only if readership does not start and end there.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BwfMf45pCwg/

My hopes lie with the possibility that Instagram poetry will serve for others, like it did for me, as a gateway to reading bigger and better things. If these books break down the initial poetry intimidation and spark curiosity, then there is only good that can come from them. That is as long as, at the end of the day, readers realize that there is more to poetry than diluted relatability and quotable sentences.

There’s a whole other vibrant world of contemporary poetry to be found in the witty, sharp tone of Billie Collins or an understated wisdom through the contemplative verses produced by Alice Oswald. If we’re talking modern love poetry, no one writes as vividly as Sandra Cisneros, or communicates as passionately as Suheir Hammad.

I hope for a new world of young adult and Instagram poetry to raise up a generation that resuscitates poetry, not a generation remembered for destroying the genre.