To help support residents on Maui affected by the Lahaina fire, donations can be made to the Maui Strong Fund where 100% of the proceeds go directly to community needs.

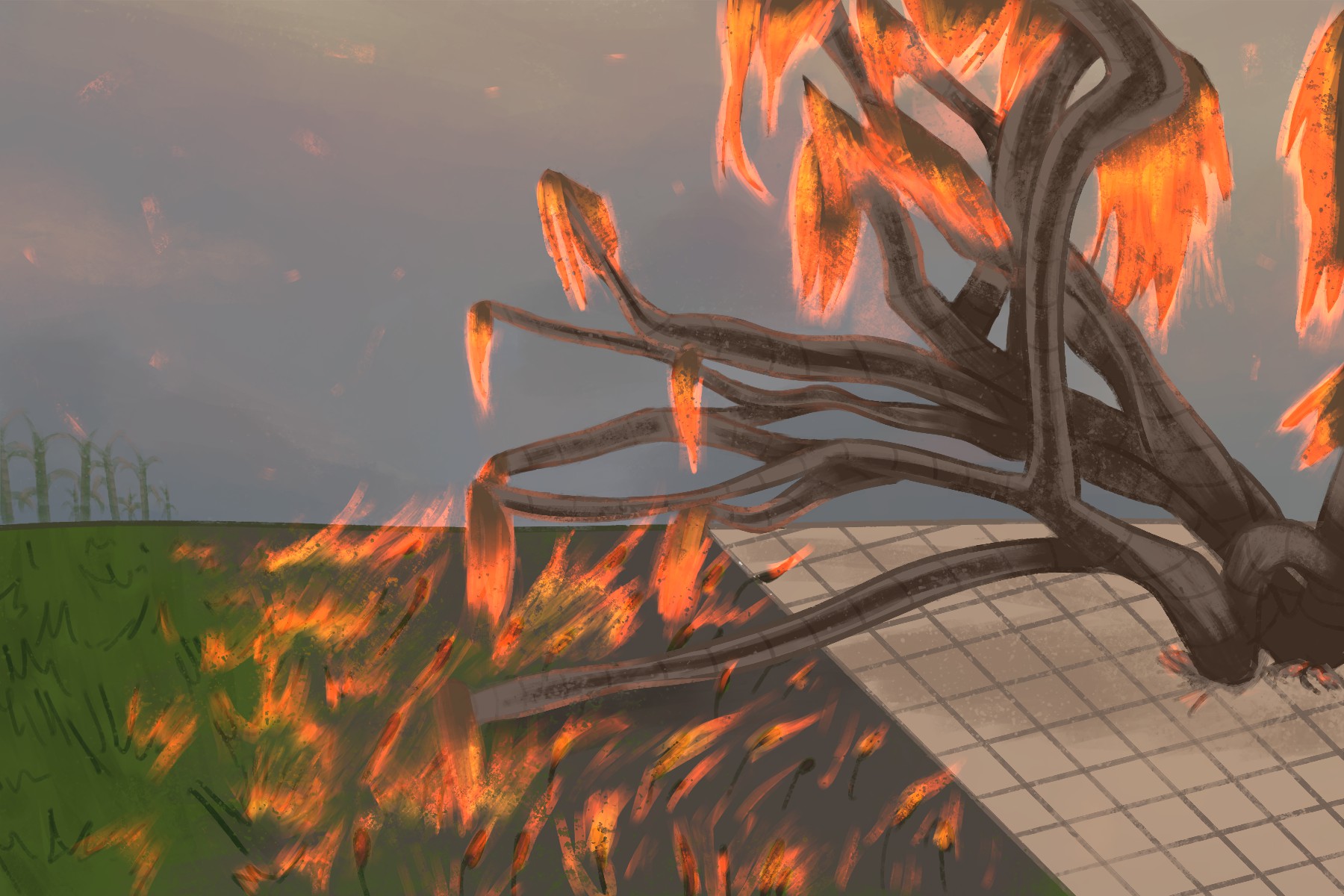

The world watched in horror as the tropical paradise of Maui burned. The unimaginable fire destroyed thousands of homes and businesses, killed over a hundred people and devastated the historical district at the heart of Native Hawaiian culture. As of late August, hundreds are still missing. The Lahaina Historic District, a recognized national landmark that stood on the same ground as the royal palace complex of King Kamehameha III, was the center of the Native Hawaiian community on Maui. The loss of life, history and artifacts during the Maui fire has impacted the Native Hawaiian community to a degree only overshadowed by their tragic history with colonialism. But Native Hawaiians have overcome devastating obstacles before, and will draw on their community and cultural resilience to forge a way ahead.

Lahaina has been a sacred place to Native Hawaiians for centuries. The location is revered because of its connection with the mo‘o goddess Kihawahine, and it acted as one of the centers of Native Hawaiian religious and political activities. When the islands were unified under King Kamehameha in 1810, he chose to locate his royal seat in Lahaina to be near the spirit of Kihawahine.

After colonialism destroyed the Native Hawaiian way of life with its sugar plantations, illnesses and thievery, colonists attempted to erase the royal seat by backfilling the area and paving it over with a public park. Today, the Native Hawaiian royal seat is buried under a baseball diamond, a chilling example of the way colonialism attempts to erase Native cultures. Despite this, Lahaina is still the center of Native Hawaiian tradition and culture.

The community that burned in Lahaina was filled with working-class people, mostly employed at tourist resorts and other businesses catering to tourism. Workers were not home as fire spurred by 80-mile-per-hour winds ripped through their neighborhoods, leaving them in a frantic race against time to evacuate the elders and children left behind. The actual number of victims killed in the inferno may never be known, and their remains may never be identified. The victims include Native Hawaiians, tourists and the most vulnerable classes: unhoused people, children and the elderly.

Many of the workers who raced against the flames never made it back home, unable to push through the heat, smoke and emergency responders. Survivors struggle to make sense of the devastating destruction, the lack of warning and how to accept such a terrible loss. Many must now make the agonizing choice between emotionally supporting family members who lost everything. or returning to work to make money for rebuilding.

The cultural center for Native Hawaiians, and the artifacts stored inside it, burned to ashes in the Maui fire. The Na ‘Aikane O Maui Cultural and Research Center was a place where tradition and culture were handed down from one generation to the next. Located on the main thoroughfare in Lahaina, the cultural center was a place for Native Hawaiians to celebrate their culture and traditions, research their lineage and history and collaborate on how to fight in court for their ancestral land back.

Ke’eaumoku Kapu, the center’s steward, found precious little when he sifted through the rubble and ashes of the center to recover what he could of the center’s artifacts, historical documents, maps and genealogy charts. Kapu, who had previously won back parts of his ancestral land with the help of the documents stored at the center, lamented the immensity of the loss when he pointed to his temple and said, “All I have is what’s in here. I just cried. Like we got erased.”

With little government help to be seen, anger is beginning to grow among Maui residents. As tourists enjoy themselves snorkeling in the blue waters next to body recovery crews, it’s no wonder. The callous attitude of fun-seeking visitors on an island experiencing an unprecedented disaster highlights the rift between Native Hawaiians and tourists. Native Hawaiians have been forced to the edges of society since colonialism, and they fear that the Maui fire will only decrease their tenuous hold on land in the area. Low wages and dead-end jobs are the reality for most Native Hawaiians, who live very different lives than the tourists visiting their home islands.

But the Hawaiian economy is dependent on those tourists as well. Tourism is the largest driver of Hawai’i’s economy, and experts estimate that 4 out of every 5 dollars spent on Maui is due to visitors. Almost all Maui businesses rely on tourist dollars to stay in the black, but many Native Hawaiians do not want visitors on the island anymore. The debate for and against tourism has been heated for years, and has become even more intense since the fire.

In the aftermath of the inferno, land speculators have begun to move in, making cold calls to mortgaged property owners and leaving flyers on cars at grocery stores. Because of the high property values at stake, devious and unscrupulous people are attempting to take advantage of traumatized victims waiting on insurance checks. In an attempt to protect Maui residents and their land from predatory land speculators, Hawai’i governor Josh Green asked the attorney general to institute a moratorium on property transactions.

Native Hawaiians are banding together to save themselves and their community, just as they have done in the past. The lack of government support for the Maui fire victims, as well as an understandable distrust for governmental agencies, has forced the local community to take center stage in relief efforts. Churches are sheltering members who lost their homes in the disaster. Families with houses still standing are taking in those who no longer have homes, and others are organizing efforts that show how the ohana spirit is still alive and well with Native Hawaiians. Surfing legend Archie Kalepa, born in Lahaina, is one of those helping to organize the grassroots relief efforts that are springing up all over the islands to support the victims of the fire.

Traditional Hawaiian culture cannot be burned away so easily. The annual Emma Farden Sharpe Hula Festival, normally held under the lush spreading branches of the massive banyan tree that shelters downtown Lahaina, was held virtually this year on Facebook at the insistence of the dancers. Even though many of them lost their homes in the fire, the Native Hawaiian dancers did not want to lose their traditions to this tragedy as well. As dance organizer Daryl Fujiwara explained to NPR, “[e]ven though we lost those places, they still remain in our stories, in our songs and our dances. And that’s how we have been able to survive.”