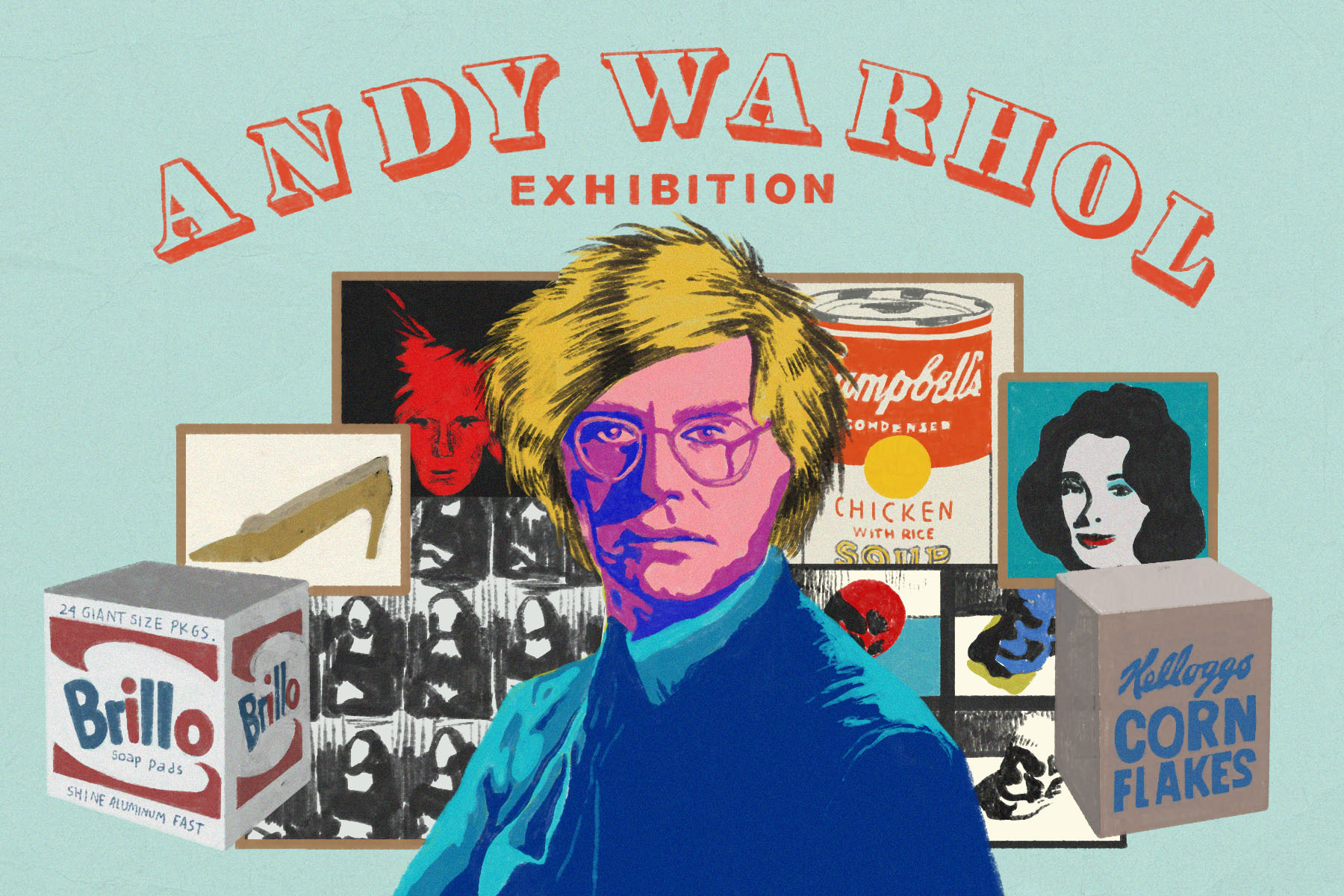

The Peter Brant Foundation’s glorious new display of Andy Warhol’s art is on view for a limited time this summer in the East Village of New York City. Titled “Thirty Are Better Than One” after Warhol’s famous reimagining of the “Mona Lisa,” this exhibition presents an expansive overview of his life’s work. A pioneer of the pop art movement, Pittsburgh-born Andy Warhol redefined art in the 1960s by changing the relationship between popular culture and the fine arts. While earlier proponents of the pop art movement began these changes, Warhol popularized the new style.

The pop art movement began in Britain and the United States during the 1950s as a reaction against the high art of modernism. Pop culture images dominate the pop art canvas, and loud colors serve as hallmarks of the brash style. From Hollywood movies to rampant consumerism, American culture forms the backdrop to the pop art movement’s cultural commentary. Leading proponents of the pop art movement include Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist and Andy Warhol. However, the “Thirty Are Better Than One” exhibition focuses exclusively on Warhol’s output and, for the most part, does not provide additional cultural context: the art speaks for itself.

Exhibition Space

The exhibition building is grand. 421 E. Sixth St. is a converted Con-Ed substation that has undergone several renovations. At one point, the space served as sculptor Walter de Maria’s art studio. The building’s current iteration as an exhibition space is marvelous. The skylight on the top floor uses the roof’s pool to create a shimmering reflection that dances around the space. The industrial brickwork and cast iron staircases form a gritty backdrop to Warhol’s colorful pop art. The cavernous gallery rooms allow viewers to examine Warhol’s art with a sense of liberty that most museum galleries can not provide. Industry meets consumerism in this space, and bright light streams in to make Warhol’s art look even more radiant.

Top Floor

A modern elevator takes viewers to the top floor to begin the exhibition. As viewers enter the skylit room, Andy Warhol’s “Self Portrait” stares directly into their eyes. The stark contrast of red and black livens Warhol’s face as he stares coldly at the viewer. His disheveled hair forms red spikes that dash across the frame, creating a striking portrait of the successful artist. The top floor also features multiple images of the “Last Supper” that fade into deep shades of blue under Warhol’s direction. Warhol’s “Camouflage” creates a pattern that resembles a tessellation; while not necessarily captivating, the painting does fill up the room. There are additional Warhol drawings located in a second room on this floor. However, this exhibition generally tends to shy away from acknowledging the important role that drawings play in teaching viewers about an artist.

Third Floor

Gallery visitors then walk down the industrial staircase to the third floor, which contains many more of Warhol’s eclectic pieces. “Dollar Sign” places the great symbol of capitalism against a backdrop of teal and red to create a disjointed feeling in the viewer. “12 Electric Chairs” examines the horror of violence by repeating the same image of an electric chair in 12 different hues. Viewers cannot escape the captivating colors on display, which force them to pay attention to the grim instrument of death. Warhol relies on multiple treatments of the same image again with “Skulls,” which uses faded pinks and greens to produce a sinister and unsettling vision of decay.

“The Kiss (Bela Lugosi)” features a hazy black and white image of an iconic moment from the film “Dracula.” Given that the film revolves around a vampire, the image’s title is ironic: a relationship that seems like a romance will soon turn bloody and horrific. Inspired by Warhol’s work in advertising, “Diamond Dust Shoes” is a more traditional portrait of consumerism. Colorful, mismatched shoes pervade the canvas to render the sheer abundance of footwear overwhelming. The diamond dust mentioned in the title is a material on the canvas that gives off a strange sparkle as viewers pass by. “Diamond Dust Shoes” is more satisfying to look at than the terrifying images that dominate the exhibition room, but it makes no less fervent a point.

Second Floor

The largest room by far, the second floor has an extremely tall ceiling. Viewers can still see the remnants of pipework when they look up, which is a clear reminder that the space has changed significantly over time. Upon entering, viewers immediately notice the brightly colored advertisements on Warhol’s cereal boxes. However, his cereal boxes are not as effective as some of his other works.

Warhol’s various efforts to capture Mao line the back wall of the room. The curator positioned the largest image of Mao to tower over the spectators below. The exhibition thus depicts Mao as an emblem of ultimate power — a symbol that Warhol playfully complicates with his unusual color palette. “Shot Light Blue Marilyn” is Warhol’s iconic attempt to capture the fleeting power of celebrity. A feigned smile with a distinct faded color scheme repulses the viewer from Warhol’s muse. Warhol transforms a pop culture icon into a cartoonish figure of scorn, masterfully illustrating pop art’s unparalleled power to warp prominent cultural images. Warhol’s classic “Campbell’s Soup Cans” drawing is yet another demonstration of Warhol’s desire to draw attention to consumerism and product advertisement through art.

The Peter Brant Foundation’s spacious gallery building in the East Village houses a truly great collection of Warhol’s work. While the exhibition may not win over viewers opposed to pop art’s brash style, it offers beautiful views of New York City from the gallery windows that are undeniably magnificent. At this New York City gallery, viewers can admire Warhol’s art in its best light.

“Thirty Are Better Than One” is on view until July 30, 2023. Tickets are available here.