Franklyn Decker, a neuroscience major at Penn State University, originally from Bowie, MD, created a non-profit organization in Haiti with a group of eight other students from his univeristy. Its name is Timoun Kontan, which means “Happy Kids” in Haitian Creole.

Timoun Kontan started as a spring break service trip to Port Au Prince, the capital of Haiti, that was arranged through a sociology class taught by Sam Richards, a professor at Penn State, thanks to his connection to the Caribbean country. “Haiti is where we saw issues we could try to help with,” Franklyn says, explaining why they chose it as the place to start the non-profit. Since then, Timoun Kontan has developed from helping building a home for children during spring break to developing community through providing education to Haitian children and economic assistance to their families. “We are trying to raise the community up and give them the tools they need to become more successful,” Franklyn states.

According to the USAID Fact sheet (2016), illiteracy remains one of the key challenge for this country, “75 percent of children at the end of first grade and nearly half of students finishing second grade could not read a single word. Half of the adult population is illiterate.” School enrollment is low, staying at roughly 75 percent, and the average years of schooling hovers around 5 years, which is mostly due to the cost of schooling. “School fees can be prohibitively expensive for low-income families,” the report points out.

Another significant key challenge to the development of the community in Haiti is lack of government oversight. “Most schools in Haiti receive minimal government oversight and are expensive relative to average earnings. More than 85 percent of primary schools are privately managed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), churches, communities, and for‐profit operators,” reported the USAID Fact sheet. At least 90 percent of Haiti’s 15,200 primary schools are non-public, many of which managed by religious organizations, NGOs and communities. This means a majority of Haitian school children rely on organizations such as Timoun Kontan for education.

The earthquake that hit Haiti in 2010 further compromised the country’s education system. Thousands of schools were erased, at least 75 percent of which were in Port-Au-Prince. The ones that were escaped the disaster were in dilapidated condition, failing to meet the safety requirement for rebuilding. Charles Tardieu, former education minister of the country, stated, “Let’s face the reality that many schools are never going to be used again, and that we urgently need other ways to revive the system.”

“We are trying to raise the community up and give them the tools they need to become more successful,” Franklyn says.

Students were not only displaced of a place to go and learn, but also of a home. The disaster crushed the dreams of young Haitians under the rubbles of their school along with bodies of their friends, family, classmates and teachers. Michel Renau, director of national exams at the Ministry of National Education, Youth and Sports, mourned the situation, “without education, we have nothing. We’ve been set back very far. But if we pull ourselves together quickly, we’ll go on.”

In that dark time, Timoun Kontan, a small non-profit organization, rose to make a huge difference in Haiti: it helps lessen the financial burden of sending children to school. The organization reached out to those kids who may not have a chance of education otherwise and ensured that they are provided with whatever they needed without forcing the family into poverty. “If a child does not have a family that takes care of them, our organization provides a home for them to live in. If a child does have a family, then we help the family support the child monetarily through a food and educational scholarship or stipend.” So far, Timoun Kontan has been able to pay for the education of several kids for the next year and provide them with a month’s worth of food and sanitary supplies.

Despite the education issue in Haiti, according to Franklyn, things are not all bad. “Honestly, this experience helped me understand how perspective can drive your outlook on life. Going to Haiti, I foolishly expected everyone there to be suffering and miserable but after arriving and getting to know the people there it put me in a new state of mind.” The effort of the Haitians in changing their life and creating a better community surprised Franklyn, “The people of Haiti are funny, intelligent, kind and loving, which I’ve come to realize are characteristics any human being can embody regardless of the circumstances they face. I really love the people and the country in general.”

Franklyn has already gone back to Port Au Prince for a second time during the summer, and he definitely has plans to continue his work with the Timoun Kontan after graduating from Penn State. “I decided I wanted to become a surgeon after taking an anatomy and physiology class in high school and shadowing a couple of doctors. I’m currently not sure how I would integrate my involvement in this organization with my future profession, but I am excited to see how it all plays out.”

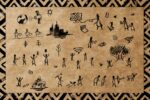

Currently, Timoun Kontan is working on a home for the children of Larousse, who are currently living in “a cramped dilapidated home.” Their goal is to place them, primarily orphans and children given away by their families, in a safe environment with free food and education. The organization also strives to reunite those who have been given away with their families. In the mean time, the children’s home will also act as a community center where children of all ages and backgrounds can come together and nurture their dreams, which hopefully will grow into positive changes to their damaged community.