Earlier this year, the University of Wisconsin-Madison began work on a groundbreaking project, one that doesn’t involve constructing a new student union or expanding the school’s football stadium. Rather, it aims to make UW-Madison the first college in the country to accept food stamps at markets and dining halls.

For McNair Scholar Brooke Evans, a first-generation homeless student and the project’s architect, the move was an important step in the right direction. Evans is part of a growing segment of the college-going homeless population in the United States. For some, the statistics may be surprising. Data from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) indicates that around 59,000 college students in the U.S. are homeless — and, due to underreporting, the actual figure may be much higher.

Furthermore, a lab at UW-Madison, where Evans served as an undergraduate research assistant and the only homeless student in employ, recently released the results of a study that surveyed students at seventy community colleges in 24 different states; of the polled students, 14 percent were found to be homeless. Looking at the numbers, it is hard to fathom why student homelessness has only recently begun to garner attention. Evans has a simple explanation: “Students like me didn’t use to go to college.”

When Evans was six, her father left her family home, leaving her mother to provide for her three children on her own. Money was tight, so Evans worked from elementary to high school to help pay rent and family bills. Her relationship with her mother, who struggled with alcoholism and saw her daughter as little more than a nuisance, was always strained. After graduating from high school in 2010, Evans began college at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. During her first midterm exams, her mother informed her that she would no longer be able to return home. At the age of 19, Evans found herself without a place to live. And so, a seemingly unending quest for housing began.

What does it mean to be homeless? It’s a simple question, but the answer is more complicated than one might expect. For many years, Evans says, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) carried a narrow definition for homelessness; only those residing in a community shelter would receive an official designation. The same was true for the FAFSA, which did not define any alternative forms of homelessness, causing Evans to believe at first that she wasn’t homeless.

Shelters, however, are simply one level on the hierarchy of homeless conditions. “There are many other people who are homeless in the cracks of society that you don’t see,” Evans says. “Those people live in their car, garages, basements, storage units, with strangers or with people from work, maybe family if they’re lucky. And unfortunately, some of them end up in sex trafficking, as I once was.”

Changes have been made. After receiving pushback from homeless advocates, HUD modified its definition of homelessness in 2012 to make it more inclusive. Additionally, FAFSA revisions that simplify the process for verifying students’ homelessness will go into effect next year, thanks in large part to the efforts of Senator Patty Murray of Washington, whose office Evans has worked with in the past.

Kevin Lee knows what it feels like to lack a permanent residence, though it wasn’t always that way. Growing up in the suburbs of Pittsburgh, his mother Tamara worked for the Federal Reserve Bank, and he had everything that a kid could ever want. Everything changed, however, when Lee was 16.

A bad snowstorm hit, leading to a flood that rendered his home uninhabitable. Lee and his mother reached out to family and friends, but received no assistance or support. Finding a place to sleep at night soon became a formidable challenge. “We found ourselves living out of trash bags, staying at different places, day to day on people’s couches,” Lee recalls. All the while, he was still attending high school. Meanwhile, Lee’s mother was dealing with several health issues. Local doctors provided little relief, so a friend from Atlanta suggested that Tamara come down to Georgia and try out the physicians there. She obliged, taking her son with her.

Upon arriving in Atlanta, Lee and his mother began rooming with the friend who had invited them, only to find that he was a gambling addict who sometimes couldn’t afford to pay his electricity bills. A search for a place to live soon commenced and ultimately culminated in a home in Covington, Georgia. Finally, things were starting to look up.

When Lee tried to sign up for high school, however, problems again arose. He was informed that some of the credits he had received in Pennsylvania would not transfer, so instead of entering his senior year, he would only be eligible to enroll as a sophomore. School officials informed Lee of a possible saving grace — the McKinney-Vento Act, a federal law that, among other things, helped homeless youth obtain transportation to and from school. When he told his mother, Lee says, she immediately said to him, “We’re going back to Pittsburgh so you can graduate.”

Lee began calling schools as soon as he got back to his hometown. He found, however, that the vast majority of them would not accept him as a student without a permanent address. Mentioning the McKinney-Vento Act did not help — somehow, none of the schools he talked to had heard of the law. At one point, Lee’s old school, located in a predominately affluent neighborhood, was ready to admit him, but balked when Lee gave an address in a predominately urban neighborhood as a pick-up spot.

Eventually, after spending some time in a homeless shelter, Lee and his mother were able to move to an apartment, allowing Lee sign up for school. After being told that he would not be able to graduate that year, he did not give up. Lee searched around and discovered a program that would let him take online classes in addition to his normal coursework. He graduated two months later at the top of his class, to the amazement of the school administrators.

Homelessness, says Evans, is an endless series of tradeoffs, “almost like making a pros and cons list for every option.” She quickly learned that even an unsuspecting grandmother could become abusive and lead one into conditions of servitude — or worse. “Is having a space with fresh linen, a pillow, a bed, door, access to water and heat enough to justify me being sexually abused?” she says. “Sometimes, the answer was yes.”

Despite constantly suffering from conditions such as scabies and infestation, Evans was eventually able to transfer from UW-La Crosse to UW-Madison in the fall of 2012, hoping for more financial aid and a better academic fit. At her new school, however, a whole new set of challenges awaited her.

At UW-Madison, Evans was often the target of insensitive and judgmental comments. An associate dean, for example, once remarked, “Even if we have homeless students, they’re probably just mentally ill.” Moreover, Evans once attempted to enter the dating scene with an out-of-state student from Rochester, New York, who told her that his mother had warned him that women like Evans just wanted to get pregnant so they could take all of his money. Needless to say, the relationship never really got off the ground. At this point, Evans says, “I lost faith in a lot of people.”

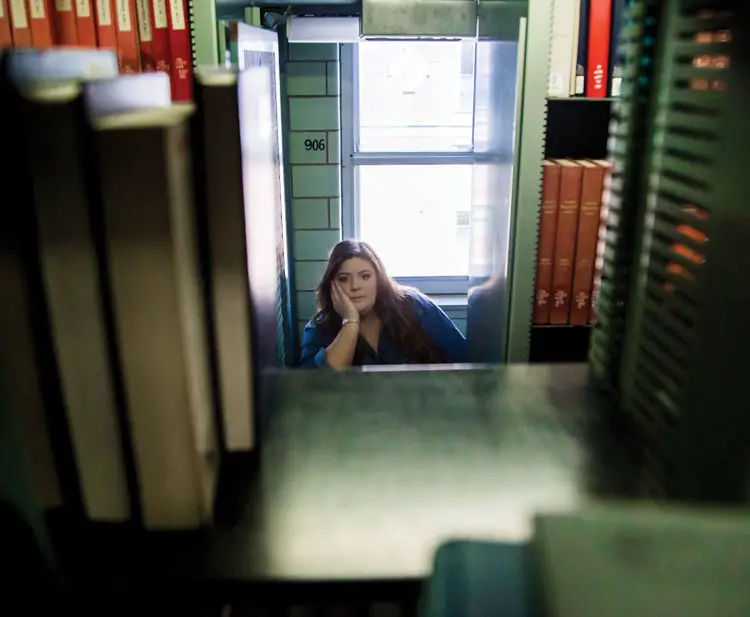

She continued to sleep wherever she could, spending many nights in her car, which was often inoperable and lacked both heating and A/C. Failing grades, however, would force Evans to drop out of school. Before she left, an adviser said to her, “You know, Brooke, lots of women leave school. So why don’t you leave, take some time off, get a good job, get married, have some kids and then can come back when you can afford it?”

As a woman, Evans was hurt by the remark and its implications. Nevertheless, she applied for readmission a year later and was accepted. She returned to UW-Madison with a renewed vigor, ready to take on the system that had, in the words of the University of Wisconsin System President Ray Cross, “failed [her].”

In the fall of 2014, Evans created a task force to tackle housing and food insecurity that was subsequently replicated at several schools across the University of Wisconsin System. Working with the student government, she was also able to create a campus food pantry at UW-Madison.

One of Evans’ major breakthroughs involved the university’s FASTrack program, which uses grants to help economically disadvantaged in-state undergraduates pay for their tuition and cost of living. Previously, FASTrack only accepted FAFSA dependent students — a tough break for students like Evans, who, by virtue of being homeless, are FAFSA independent. After much campaigning and the hiring of a new financial-aid director, the financially dependent clause was removed. The retooled FASTrack program will commence this fall.

For Evans, who has racked up over $85,000 in student loan debt, the news was bittersweet. “You can do a lot of work in this area,” she says, “but by the time your changes get implemented, you’ll probably be gone.” Still, she has pushed on with her work. In recent years, she has testified for the National Commission on Hunger, presented on student homelessness and food insecurity for the Obama administration and published a chapter in a book. One day, Evans hopes to create the first national scholarship for homeless college students.

After a chance recommendation by a friend, Lee found his way to Paul Quinn College. During his first semester, he won a business-pitch competition to start a food truck venture in the area around campus, a federally recognized food desert. With the assistance of Paul Quinn president Michael Sorrell, whom he views as a mentor and father figure, Lee was able to participate in internship programs like INROADS. In 2015, he was designated an HBCU All-Star, which enabled him to work with the White House on initiatives to assist homeless students.

Though Lee is majoring in Business, he hopes to go to law school and possibly work in commercial real estate someday. He maintains a close relationship with his mother; when she stayed in a shelter in Fort Worth recently, he made the half-hour drive to see her every day. Lee is currently working on an initiative he created called “Homeless to Hopeful,” which seeks to help homeless students become independent upon graduation by pairing them up with sponsor families.

When it comes to making sure that homeless students get the same opportunities as others, Lee says that having homeless liaisons would be beneficial; Evans adds that having case managers could also help. But more importantly, Lee says, people need to realize that anyone can be homeless, not just “someone living on the street, someone panhandling for money,” as he himself once thought.

Students must also learn how to identify their own homelessness. Many of them, Lee says, fit the definition of homeless, such as those who sleep on the couches of friends, but fail to recognize their situation. Others, as Evans points out, still struggle to describe themselves as homeless, due to the associated stigma and stereotypes.

Schools can also do more. A shift in philosophies may help; according to Evans, many colleges have adopted a utilitarian model that prioritizes small improvements in preference satisfaction for a majority of financially secure students over large improvements in the quality of life for a minority of low-income students. In addition, Evans says schools are unwilling to acknowledge or research more into their homeless populations. “They don’t want to know,” she explains, “because knowing then entails a duty, and they just don’t want to deal with it.”

Colleges would do well to pay more attention to students like Lee and Evans, who have much to tell. Of course, as Evans brings up, getting too caught up in individual stories, especially the successful ones, can be harmful. After all, no one person can represent the entirety of a movement on their own, and experiences vary greatly. For instance, Paul Quinn College is a private school with an enrollment of fewer than 500 students, while UW-Madison is a public flagship with a student population over 43,000.

But taking the time to listen may inspire perhaps the most important qualities of all—compassion and empathy. It’s no secret that the homeless community is still heavily stigmatized in the United States. As Evans notes, for example, she was alive when the New York Supreme Court helped guarantee homeless citizens the right to vote. And who hasn’t heard the classic story of a small child who sees a homeless person outside and hands them money or a meal? The trouble is, says Evans, these tales usually just garner praise for the donor, and the individual in need becomes lost in the picture.

In the end, we must remember that those who are homeless are regular people; they look many different ways, they do many different things, they work jobs and they have talents. As Lee put it, “Don’t treat me a certain way just because of my circumstance. Don’t just assume. Really get the backstory of individuals’ lives and help them from there.”

Evans, who has accepted a fellowship after graduating in May, is currently searching for her next living situation, and Lee is moving into his final year of college. Though the future is uncertain, one thing is for sure: They, and thousands of other homeless students across the country, will continue to fight for a better life and a more equitable future.

Brooke Evans is a new graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and can be reached by email at brooke.evans@wisc.edu. Kevin Lee is a rising senior at Paul Quinn College and can be reached by email at KLee309@pqc.edu.

[…] los indigentes METER A LOS QUE FÍSICAMENTE TIENEN SU HHOGAR EN LA BIBLIOTECA ¿SERVICIOS PARA INDIGENTES? DUCHAS, SERVICIOS SOCIALES, ELLOS TAMBIÉN SON UNOS OLVIDADOS = ESTUDIO JOSE ANTONIO GOMEZ SACAR ALGUNA FRASE = https://studybreaks.com/2017/07/01/homeless-in-college/ […]