Virtual reality started off as a form of entertainment, and it kept people amused in a variety of ways; it made their friends look goofy as they watched a video on a huge headset, and it allowed them to watch the horror video games on the “Let’s Plays” YouTube channel.

Although specialists have been developing VR since the late 1980’s, Oculus Rift pioneered the current technology since its release in 2016. Currently, more uses of augmented reality are rising into existence, such as VR journalism.

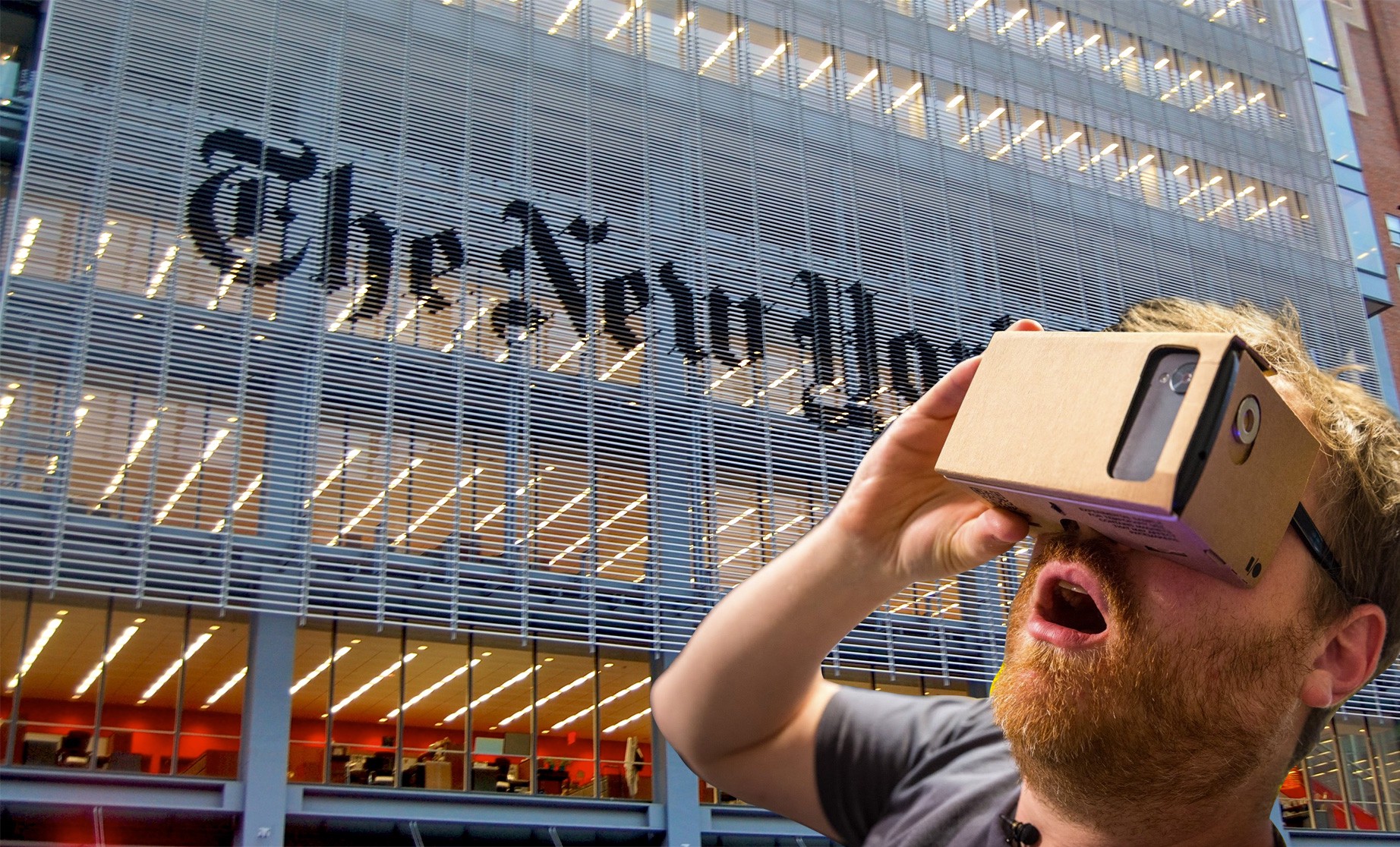

VR doesn’t just focus on entertainment anymore since it’s inching its way into journalism. In fact, Washington Post and New York Times are both dipping their toes into the VR journalism trend. Washington Post created 360 videos for its readers to watch events as a whole rather than a journalist report.

So far, its videos capture larger events, such as the catastrophe in Florida after Hurricane Irma, the Women’s March in D.C. and democratic events, such as the Virtual Democracy Plaza, which is a space for people with VR headsets to join in a virtual party, either their own or one hosted by NBC, about the presidential debates.

Moreover, New York Times caught on to the VR journalism trend in 2017 with the 360 series called “Life on Mars.” Produced by Nick Capezzera, “Life on Mars” is a short series about NASA astronauts living in the Mars-like conditions of Mauna Loa, Hawaii.

Unlike the Washington Post’s VR videos, “Life on Mars” immerses the viewer in the training videos with scientists talking directly to the camera, as if the viewer is also training with them.

VR journalism immerses the viewer in a way that journalistic reporting can’t quite achieve. For instance, the viewer experiences the event for themselves rather than having a reporter narrate it to them. However, some people think VR journalism can take it up a notch to a room-scale virtual reality.

How does a room-scale virtual reality differ from augmented reality? While both deal with a person interacting with the world through different lenses, room-scale virtual reality definitely has more immersion with a narrative than augmented reality.

According to NBC News, virtual reality is the replacement of the normal reality with a computer-generated 3D reality, and it ranges from the Oculus Rift for games and 360 videos to room-scale environments.

Moreover, augmented reality still deals with the physical world around a person but is seen through, and maybe even interacted with, a lens, such as Google Glasses, or a screen, similar to Pokémon Go.

Naussica Renner from the Columbia Journalism Review imagines the viewer being able to have the ability to “choose their own path” of the story with virtual journalism on a room-scale.

Room-scale virtual reality dedicates an entire room to a virtual reality experience, including scene-setting and 3D objects to interact with. Renner believes it can open up the reader’s experience of journalism beyond the traditional written or streamed journalism.

The participant is able to immerse themselves in a crowd and follow up on periphery stories or stand off to the side and watch the whole story unfold before them with no interference. Either way, the participant experiences the news how they deem fit.

Moreover, with fewer editorials due to direct user immersion, VR journalism could very well eliminate the gatekeeping of editors and publishers and skepticism of bias because the user controls the story. Naturally, people want to follow the position of the action, but VR journalism also allows participants to follow peripheral stories and exhaust every minute detail of the story.

Journalism started off as the platform for bringing awareness of the events occurring in the world. Just as people innovate and adapt their technologies to respond to the world around them, so too does journalism with VR.

Just after streaming events was the trend for people receiving the news, VR journalism brings a new frontier to journalists and a new perspective to their audiences. With this in mind, VR journalism is not just about “choosing your own” story for news but also about the change in experience with a room-scale VR journalism.

Before the technology is cheaper and more accessible to the public, CJR wanted to investigate the effects of VR journalism on participants, from attention levels to brainwaves to heart-rate. CJR’s research team collaborated with Multimer, a company that studies feedback from people to help improve designs of products, and Associated Press.

The AP Study on VR journalism has shown a heightened open-mindedness about the issues participants saw after they were immersed in the room-scale VR journalism. CJR summarized that war zone reporting in a room-scale VR journalism setting stimulated the participants the most, which can give them a memorable experience of the story.

Furthermore, VR journalism about science and the environment built more open-mindedness in participants than traditional newspapers or reading from a screen. Moreover, Multimer concluded that VR journalism is best for exploratory topics, such as science and nature.

Although CJR’s room-scale VR journalism is conditional on cost and accessibility, the AP study with Multimer recorded the effects of room-scale VR journalism on participants and what specifically makes the news and information memorable. VR can innovate journalism not only as a way of receiving news but also a way of presenting the news for journalists.

Once room-scale VR journalism is accessible to people, journalists and their editors — perhaps even webpage designers — may need to uphold a similar standard of gatekeeping information and allow the reader to exhaust all curiosities about their topic.