DNA ancestry tests, which help people find long-lost relatives and build family trees, have risen dramatically in popularity within the last several years.

With companies such as 23 and Me, Ancestry DNA, My Heritage, Family Tree DNA and Geneographic Project all offering autosomal ancestry tests, it can feel like buzz about the kits is everywhere.

Using the tests, people can find out what percentages of the different races they are, connect with potential relatives and estimate their relation to said relatives (e.g., first cousin, third cousin, etc.), create a raw DNA file for uses outside the site and even analyze how much of a trace of Neanderthal their genetic material has.

However, despite all the good the tests can do, critics have suggested that they might be reinforcing a white bias.

Because most companies rely on preexisting databases to source their genealogical data, makers of ancestry tests find themselves with a much larger quantity of information regarding European and Anglo demographics than those of other races.

Indeed, Ancestry.com makes a specific note to inform users that most of their historical records heavily favor those of European, U.S., Canadian, Australian or New Zealander backgrounds.

While their intent is not to favor those of white ancestry over others, simple realities about historical record-keeping make the issue nearly unavoidable.

For instance, African Americans have an especially difficult time when it comes to ancestry tests and genealogy, as their ancestors were brought to America as a part of the slave trade. As a result, little to no information exists about their genealogy prior to when they arrived in America.

In the antebellum period, records only showed the age and gender of the enslaved ancestor, which makes it almost impossible to trace further back. At best, many African Americans can only trace their ancestry back to the Civil War when they first received official documentation.

Specific databases for African American ancestry, such as the Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil War military records, can help bridge the gap though.

For Latinos, family-tree research can also be exasperating. Many Latinos have European, African and Native-American ancestry, including other regions as well. They may be able to trace their European side back many more generations than their African or Natives sides.

Plus, oftentimes they live in a different country than the one their ancestors came from, and sometimes those countries may not have their records online. If this happens, then anyone interested in mapping out their family tree would have to literally visit their ancestral country to comb through the necessary records.

Native Americans, too, have a difficult time getting their money’s worth from ancestry tests, as many lack the necessary information to point indigenous people toward the specific tribe of their origin.

Native American tribes differ greatly in history, culture and appearance, but tests that only reveal “Native American” or do little in helping their users know whether they’re Blackfoot, Comanche, Sioux or any of the other hundreds of indigenous peoples. These are the same tests, though, that can accurately identify regional identity for Europeans.

In addition to providing a paucity of historical records for non-white users to work with, the tests also rely on what are called reference samples, which are problematic in their own regard.

To estimate a person’s ethnicity, the companies compare the customer’s DNA to the DNA of a group of people with known ancestry to certain regions of the world. Unfortunately, testing companies have significantly less data for African and Asian countries than they do for people of European descent.

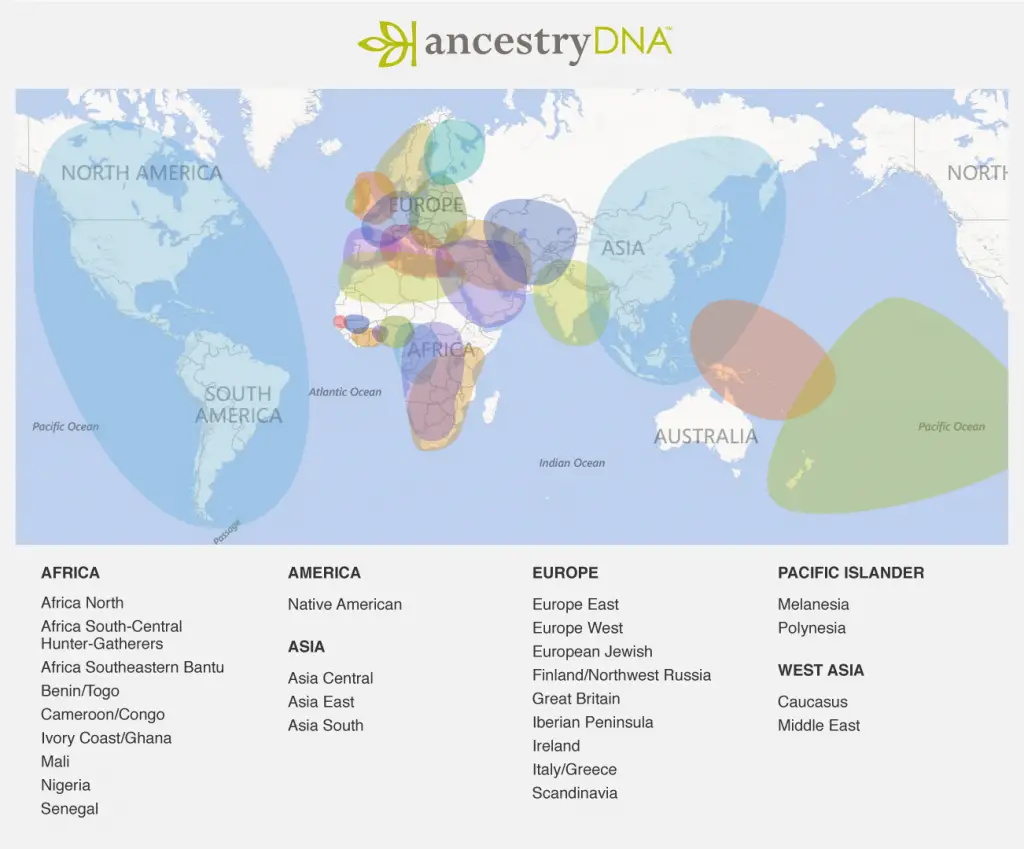

For example, on Ancestry.com, of the 26 regions available, regions from Africa (Cameroon/Congo, Benin/Togo, Mali, Nigeria, Ivory Coast/ Ghana, etc.) ranked 11th – 21st for the most reference samples collected; compare this to the number of European samples (Great Britain, Ireland, Europe West, Italy/Greece, etc.), which ranked mostly top 10.

The only other regions with a low number of samples were Asia, Melanesia and Polynesia.

23 and Me even acknowledges this bias on their website under the sub-title “Confronting Bias”: “…we have the most reference data from European populations, and we are able to distinguish more sub-populations from Europe than from any other continent.”

To combat this implicit bias, the website has launched several data-mining projects, such as The African Genetics Project and another endeavor funded by the National Institutes of Health to test people of mixed race for genetic diseases.

Health portions are included in some of the DNA tests, such as the one offered by 23 and Me, if you choose to pay for it. Rather than relay critical medical information, these tests are usually more geared toward entertainment purposes, such as revealing whether you’re more likely to enjoy bitter flavors, have brown eyes and or lose weight easily.

Some tests include aspects that allow the customer to see whether they are carrying a certain disease or are inclined to be carrying one. Again, however, due to the fact that there isn’t as much medical information available for minorities, the tests pull from a smaller sample size, meaning that their genetic health information may not be as accurate compared to their white counterparts.

In general, the danger behind these tests lies not in any explicitly racist behaviors, but rather that their service, unintentionally, serves as yet further reinforcement of the idea that white races are the standard and others are variations.

If anything, the historical databases are the ones to blame, not the companies themselves, but they would do well to continue investing in efforts to equal the genealogical playing field.

Efforts put forth like the one from 23 and Me, that are working to gather more ancestral data from under-recorded areas, represent the next logical step in the industry. Providing available data is obviously the first move, but offering currently unavailable data is the new, exciting future for DNA testing services.