Facebook has had a rough go of it in recent months. The Cambridge Analytica situation received so much attention, most of it negative, that their CEO and founder, Mark Zuckerberg, testified before Congress about how the site functions.

Twitter has had similarly bad press, more geared towards its difficulty with curbing harassment. Despite this, however, Facebook and Twitter remain the two biggest names in the social media market today.

But that might change. The Internet hosts plenty of radical programmers and designers, and a few of them are intent on realizing their own visions for social media networks of the future — networks without the problems and liabilities faced by today’s juggernauts.

Some networks, like Frendica and Diaspora, aim to displace other forms of social media by essentially doing what Facebook does, but better. Another program, Mastodon, aims at being a more specific Twitter-like platform for microblogging across thousands of unique “instances,” or groups of networked users.

Here’s what alternative social media is poised to handle better than its predecessors — and the one thing it hasn’t caught up on yet.

Harassment Prevention

Twitter has been struggling for some time with policing and removing abusive members from its networks, preventing them from harassing other users. They’ve dealt with this problem, in part, by cracking down on accounts deemed suspicious by computer and human moderators.

Some critics claim this isn’t effective enough, and that Twitter isn’t doing enough to protect its users. Others say the approach is too strong, or that accounts can be banned for free, harmless speech.

There’s a real discussion to be had about what kinds of speech should and shouldn’t be allowed on social media, but most people tend to have their own opinions about what is or isn’t acceptable based on context. That’s part of the ethos behind Mastodon’s means of addressing harassment: let each smaller network, or “instance,” police itself.

Since Mastodon is a decentralized network, there doesn’t need to be one set of all-encompassing “terms of service” for all of its users — smaller groups of users determine and enforce their own rules in small communities that can still communicate with other Mastodon users outside their network.

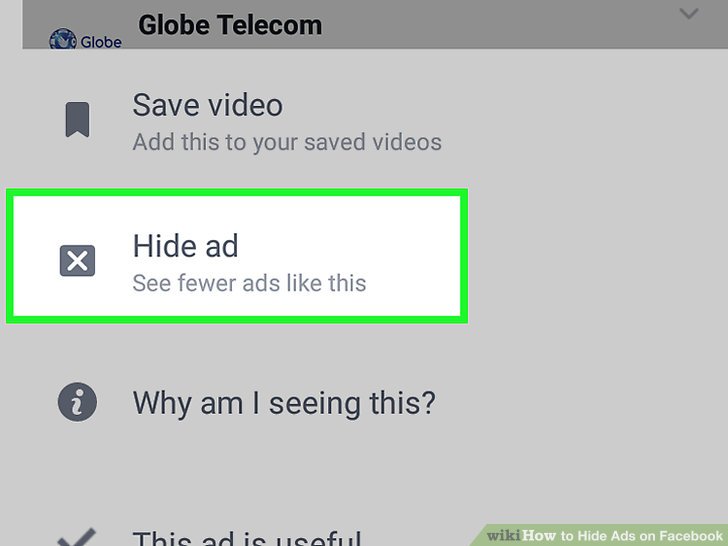

Advertising

“Senator, we run ads,” was Mark Zuckerberg’s wry response when Sen. Hatch asked how Facebook can afford to run without charging its users. Facebook and Twitters’ advertising programs make them tempting targets for hackers, because of the ways in which social media collects and analyzes content posted by the user to target ads to micro-specific audiences.

That concern over targeted ads — or “sponsored posts” and the like — motivates plenty of alternative social media networks to eschew the typical model of advertisement-reliant sites. Mastodon suggests its users crowd-fund their own networks, but also accepts donations for some of its larger instances, so those with the pocket change and the civil inclination to support the network can do so.

Privacy

Back in 2013, a handful of Facebook users noticed a disquieting trend: Pictures of their own faces from their profiles were being used to generate Facebook ads that were being shown to other users. People’s faces were being used as tools for advertising without their awareness. Facebook later confirmed that this was not a mistake of some kind, but instead covered in their terms of service at the time.

A legal point that confuses many users is that, when you upload an image to a social media website, that image frequently becomes that website’s legal property. The “terms and services” section that most people just skip over frequently contains information on what you permit the company to do by signing up, including what it can do with your information and likeness.

Facebook gathers and uses as much information as it does in the first place to support its advertising business, but because alternative social media doesn’t need advertising to run in the first place, it starts right off with a big advantage, privacy-wise.

Privacy on the internet requires more than reading the terms and services, putting duct tape over your laptop’s webcam or changing your password to something harder to guess than “password” — it’s also a question of letting different people see different things.

Control

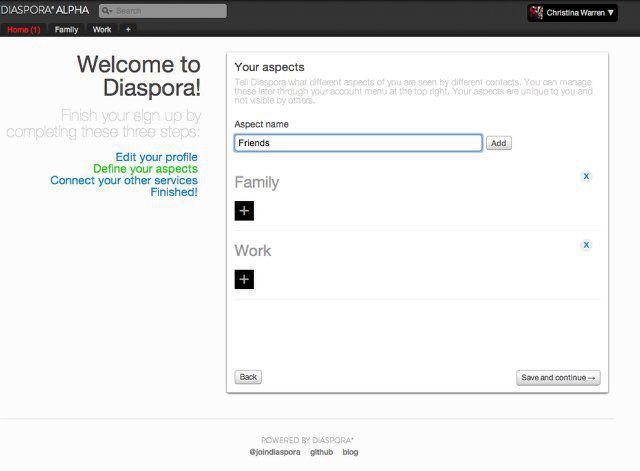

Social media networks like Mastodon and Diaspora give its users a lot of control in compartmentalizing what gets shown to their peers. I know I’ve had relatives tell horror stories of people losing their jobs for posting stuff on social media their employers didn’t like, and I’m sure being reluctant to post something because of the knowledge that your dad or whoever can read it was a universal feeling for everyone who was growing up in the 2000s.

It’s a bizarre problem. Most people don’t normally socialize while acting like their parents, professors or bosses are present 24/7 — that would be exhausting, and there’s no way that they’d appreciate your friends’ inside jokes anyway. But when you interact with people through your Facebook wall or Twitter feed, it’s like you’re interacting with everyone you’ve connected to on those networks in the same way.

That’s why what I see as the most promising feature of alternative social media is what Diaspora calls “aspects,” or the option to group your connections into different categories based on how you know them and what kind of things you’re going to want to share with them.

Facebook offers choices like sharing content with friends of your friends or just your friends, but aspects are more discriminating than that: You can have an aspect for your work buddies, for your family and for friend groups in different cities, and only share stuff in each that you want that particular group to see.

Aspects make social media more like socializing in real life by giving you more control over who sees what you’re sharing.

The Downside

Of course, the biggest problem with most alternative social media websites remains the biggest advantage for traditional social media — most people haven’t heard of them. After all, it’s hard to be social on a network if there’s nobody else there to be social with, and most people are already on the big ones. That’s been the downfall of plenty of social media websites.

There’s a mitigating factor here, though. Some of these sites allow for posting across different platforms: Diaspora, for example, can be used to post on Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr, depending on your settings, so you won’t necessarily have to just abandon everyone you know who doesn’t switch with you.

I think that the useful features and bold innovations present in these newer social media sites at least herald what the future of social media might look like, beyond what Facebook and Twitter currently offer.