In 1985, Margaret Atwood revolutionized dystopian fiction. The genre, already illuminated by gems like “Brave New World,” “1984” and “Fahrenheit 451,” certainly was not lacking in popularity, so how did an author with a modest following completely transform a category of fiction? In her book “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Atwood introduced a groundbreaking new character: the dystopian heroine. Thirty years later, the author is adding to the beloved story. “The Testaments” will chronicle the experiences of three women living in a misogynist’s utopia. So, what do audiences need to know about the anticipated sequel?

“The Handmaid’s Tale” follows Offred, a woman living in the oppressive Republic of Gilead. Prior to the events of the novel, this entity overthrew the United States government and banned the Constitution. New rulers cling to a hodgepodge mix of extremist Christian beliefs, using the doctrines to justify their tyranny. As you can imagine, the situation spirals out of control.

Nuclear and radioactive waste linger throughout the land, and as a result, most of the territory is uninhabitable and thousands of women are infertile. The new government must find a way to overcome these threats. Soon, officials round up infertile women, political rivals, homosexuals and dissident religious groups, and force these outliers to clean up the toxic sludge.

A different fate awaits women still capable of conception. One by one, these women enter the “Rachel and Leah Re-Education Center” and train for their new lives as breeding stock. After graduation, each woman receives a new name based on the official with whom she will procreate. “Offred” literally means “Of-Fred,” cementing the protagonist’s status as an object. At least, that is Gilead’s goal.

Throughout the novel, Atwood ponders the effects of legal dehumanization. Is there a limit to its damage? Gilead reduces Offred to an object and revokes fundamental rights to ensure her compliance. The somber heroine no longer enjoys voting rights, compensation for her employment or even the luxury of reading a good book. Despite her superficial subjugation, Offred harbors a rich internal life, a telltale sign of autonomy.

Authorities forbid all primping, but Offred rubs butter on her hands to soften them. The dour heroine gazes at flowers in the garden and remembers her own green thumb. The smell of freshly tilled soil haunts her mind. Although painful, the memories attest to one reassuring fact: She is still a sentient human being.

The sequel’s exact contents remain a mystery, but similar musings on dehumanization are bound to occur. After all, this theme is a trademark of dystopian fiction. “The Testaments” will almost certainly tackle questions like, “How much can rulers really reduce a person’s humanity?” However, these inquiries will spring from the lives of a new group of women.

My analogue body can only be in one place on publication day but you can join me for the launch of THE TESTAMENTS as tonight’s event will be live-streamed to cinemas worldwide. Here is how to get your ticket https://t.co/INalp0FhYh#TheTestaments

— Margaret E Atwood (@MargaretAtwood) September 10, 2019

In “The Testaments,” Atwood aims to follow “characters that were already there.” Although she provides no further clarification, the original novel is overflowing with potential protagonists. Gilead separates women into five distinct groups: Handmaids, Wives, Econowives, Marthas and Aunts. More than likely, the sequel’s potential heroine will function within one of these categories.

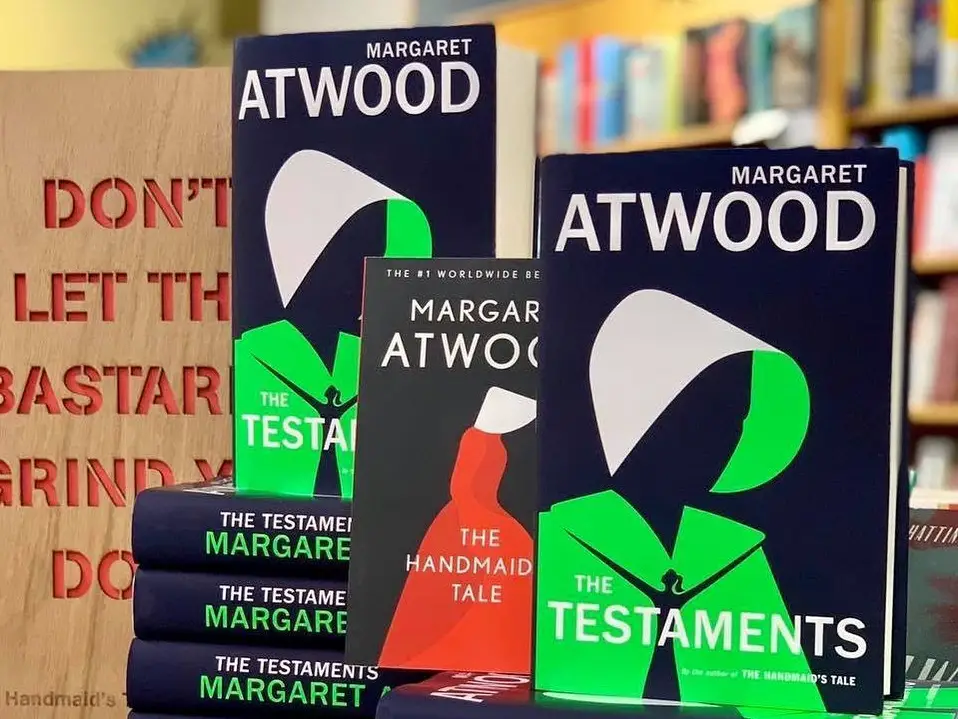

The cover art for “The Testaments” might even contain a clue about which group will step into the spotlight; from what we’ve seen, it features the figures of three women. On the front, a woman clad in green wears the white bonnet of a handmaid. In Gilead, only Marthas wear green, and the government does not consider their faces attractive enough to hide with a bonnet. If color symbolism is at play here, the Marthas’ green garb will likely surface within the novel’s action. At this point, the other two women on the cover remain an intriguing mystery.

Atwood is committed to preserving this mystery, but she has offered more insight on the book’s inspiration. After announcing “The Testaments,” she explained, “Everything you’ve ever asked me about Gilead and its inner workings is the inspiration for this book. Well, almost everything! The other inspiration is the world we’ve been living in.” Obviously, the author’s dual influences are both chaotic.

Off we go.., pic.twitter.com/s2bK5iVIRf

— Margaret E Atwood (@MargaretAtwood) September 4, 2019

If Atwood plans to reveal Gilead’s inner workings, then readers should prepare for an exploration of its methods of subjugation. Throughout “The Handmaid’s Tale,” nonconformists vanish, leaving the passive heroine to speculate about their fate. In “The Testaments,” readers might accompany these rebels into Gilead’s torture chambers — or worse. In “1984,” readers follow Winston Smith as he rewrites history, rebels and succumbs to the torment of Room 101. Since this famous dystopia originally inspired “The Handmaid’s Tale,” might a similar investigation take place in its sequel?

Of course, one pressing question rises above the rest: What happens to Offred? At the end of “The Handmaid’s Tale,” her fate is uncertain, leaving readers to agonize about their protagonist’s safety. “The Testaments” will begin 15 years after the stoic heroine disappeared into a suspicious van. Will the sequel reveal her ultimate whereabouts? Does Offred reunite with her husband and daughter? At this point, fans can only speculate about the character’s final destination.

Since its secrets remain well-hidden, the content of “The Testaments” has ignited intense speculation. Although the plot remains shrouded in mystery, fans can count on one thing: The novel will not shy away from the grotesque. “The Handmaid’s Tale” attests to this element, since crippling misogyny, humiliating rituals and public hangings are commonplace in Gilead.

Still, any horror within the sequel’s pages will seem perfectly attainable. After all, the best dystopian novels present plausible, almost familiar scenarios, and Atwood’s works are no exception. When describing her initial writing process, the author remarked, “I made a rule for myself: I would not include anything that human beings had not already done in some other place or time, or for which the technology did not already exist.”

As it turns out, the dystopian heroine existed long before Atwood committed her to paper. She functioned within that “other place or time,” in her own Gilead. The genre resonates with women especially and details a subjugation all too familiar to heroines. Upon its release, thousands of women will no doubt flock to purchase a copy of “The Testaments” and see what else is in store.