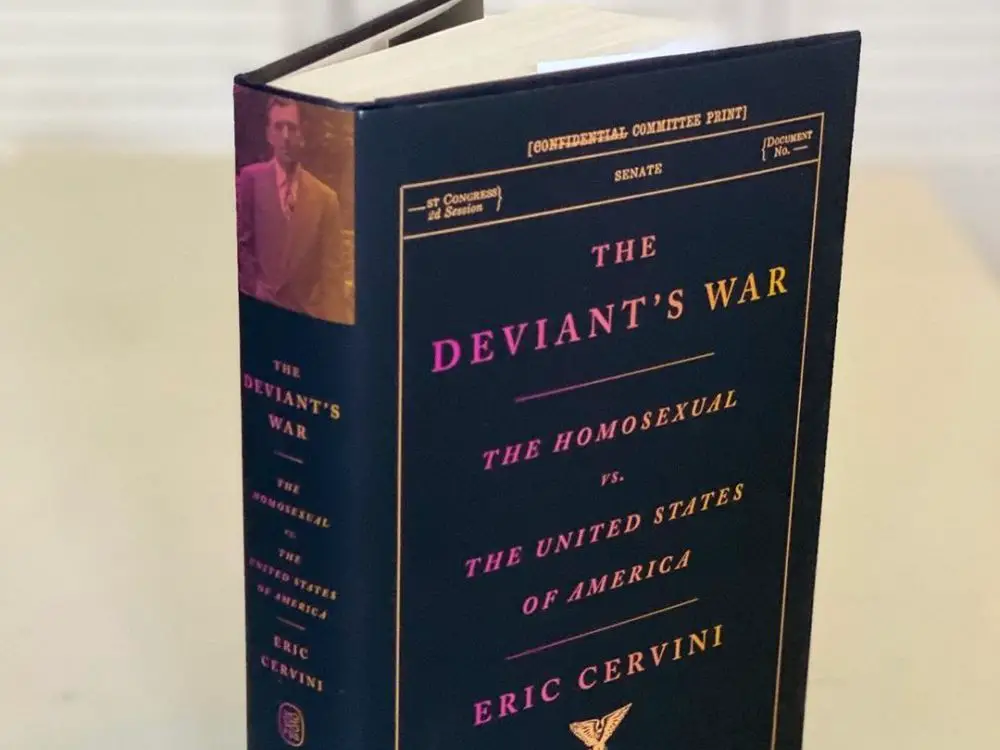

If one were to stop someone on the street and ask them to pick a defining moment in the pursuit of gay rights in America, the majority would probably describe the Stonewall Rebellion. On June 27, 1969, a group of racially diverse patrons at the titular gay bar stood up against police harassment. For many, it is seen as the moment when the gay revolution commenced. However, in his new book “The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual v. the United States of America,” Harvard and Cambridge-educated historian Eric Cervini explores a lesser-known epoch of queer history: the homophile movement of the 1960s.

Among the myriad forces behind the movement, Frank Kameny played a considerable role in nearly all respects. A Harvard Ph.D. graduate persecuted by employers due to his homosexuality, he founded the Mattachine Society of Washington in 1961. The organization, just one chapter of a larger, nationwide coalition, protected gay men against purges in the federal government during Senator McCarthy’s witch-hunts.

Nevertheless, it eventually became an object of contempt for many who lamented its exclusionary tactics to keep the riff-raff from sullying what was otherwise a highly respectable approach to social activism. Although the movement preceded and is often eclipsed by the more militant, diverse demonstrations organized post-Stonewall, “The Deviant’s War” nevertheless evokes our current moment through descriptive parallels drawn between the homophile movement and the black Civil Rights Movement.

The rainbow flag is a symbol of unity and exclusion. In its deconstruction of whiteness into its array of hues, the definitive icon of the gay community muffles the voices of brown and black persons. While new symbols have emerged to counteract this white supremacy, many find fault in their focus on people of color.

Cervini’s “The Deviant’s War” may describe a fight largely fought by white men, but it shouldn’t be a surprise that an activist group formed in mid-20th century America would be influenced by the domestic fight for racial equality. Kameny, in his defense of homosexual rights, reflected on the plight of black Americans as a way to undermine the supposed immorality of deviant sexual practices. However, what is rather enlightening to consider is how the issues plaguing both the gay and black communities are bound by the abuses of law enforcement even in the present day.

As “The Deviant’s War” reveals, one of the central issues facing gay men was the fact that the U.S. government viewed them as a security threat and vulnerable to Soviet blackmail. The problem of revoking security clearances for homosexuals in the 1960s may be viewed as an analogue to a current debate in criminal justice: Should a criminal record bar an individual from employment in the future? One position undergraduates hear is that colleges should not ask whether a student has committed a felony during the application process.

Such a question, proponents argue, discredits a student that may otherwise receive admission to their dream school. To require a potential student to report a history that may have no connection to their current lifestyle, and may have been unfounded to begin with, is to create a criminogenic admissions system that stifles upward mobility, persecutes poor people of color and maintains the exclusivity of higher education to the white and spotless elite.

While activists today often consider the intersectionality of people when deciding how to enact social justice, the homophiles were rather homogeneous — nearly all of the Mattachine Society’s members were white men. However, the struggles of this privileged demographic represented a far more diverse gay world. For all gay men in America, not only did they encounter systemic prejudice in federal employment, but their physical bodies were violated as a result of discrimination, from police entrapment to subsequent suicide as their job opportunities vanished. “The Deviant’s War” involved economic despair as well as physical limitations.

The preoccupation with the male body, regardless of race, has been characteristic of police in the United States for decades. Under stop-and-frisk legislation validated by the 1968 Supreme Court case “Terry v. Ohio,” police were given the right to search individuals based on “reasonable suspicion,” a nebulous standard whose dubious constitutionality has been the subject of debate for decades. For those in uniform, the masculine figure of a minority became another object to search, peruse and explore. The likeness of sexual harassment to Terry stops — a burden carried by countless African Americans — becomes unavoidable when we consider the history of policing homosexuals.

Throughout the mid-20th century, police officers invaded gay men’s privacy — the right to which remained up in the air until the decision of “Griswold v. Connecticut” in 1965 — through entrapment strategies such as camping out in public restroom stalls or using binoculars to spy on “sodomites.” Police officers became voyeurs to the masculine physique for the sake of justice. In the courtroom, gay men like Kameny were subjected to intensive questioning about the activities of homosexuals, making what is fundamentally a personal matter criminally sensational.

As gay activism in the 1960s abandoned respectability for all-inclusive rioting, Cervini conjures essential questions to consider when it comes to effective activism. At once, Kameny represented a group of polished individuals who considered picketing a radical concept while at odds with the riots on Christopher Street. Yet the Mattachine Society found itself obsolete by the end of the decade as it was supplanted by more vigilant activist groups like the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activists Alliance. The GLF’s support of bar raids — which brew animosity between gays and law enforcement, driving the former to activism — represents a fascinating feedback loop; as more discrimination occurred, the movement grew alongside it.

And grow it did, graduating from the narrow Mattachine membership to include poor, black and Latinx youth of all hues on the spectrum who weren’t afraid to make a ruckus. The fact that this movement became diverse rather than uniform, militant rather than respectable, says a lot about the stages of activism and what it takes to transform society.

“The Deviant’s War” represents but a fragment of a broader social movement that continues to this day for LGBTQ+ Americans. Under immense pressure to act on racial injustice, the country would benefit from a reflection on both how its policies have negatively affected two intersectional minorities as well as how their movements created real change. As Americans fight over how best to protest, they should keep in mind that the issues plaguing the nation are ubiquitous and tenacious, and that it is only through an array of tactics that the country will achieve equality for all.