Bestseller’s Remorse

When books are marketed to large audiences, disturbing themes can find their way into the hands of unsuspecting readers.

By Alicia Drier, Roosevelt University

I did it again. I picked up a book at the front of the bookstore just because it had the word “bestseller” attached to it.

Who knows if it will be any good? Though I’ll be able to talk about it when my friends go see the movie adaptation next summer, the magical bestseller label can often be rather disconcerting. In a world where books are marketed in the same way as movies and television, readers are choosing to buy into stories without knowing all of the details.

I’m not talking about books like “Fifty Shades of Grey” or “Two Boys Kissing,” even though both made it on the 2015 list of the top ten most frequently challenged books. Texts on the banned-book list are not often veiled in their subject or agenda, allowing readers to make an educated decision about whether or not to read them before even picking up the book.

Banned book author John Green recently stated in a YouTube video that, “Text is meaningless without context,” or, more specifically, the parts do not determine the whole when it comes to a good piece of literature, and that is where my concern comes in. More and more books seem to be pulling readers in with one subject, without full disclosure about the other content covered in the book.

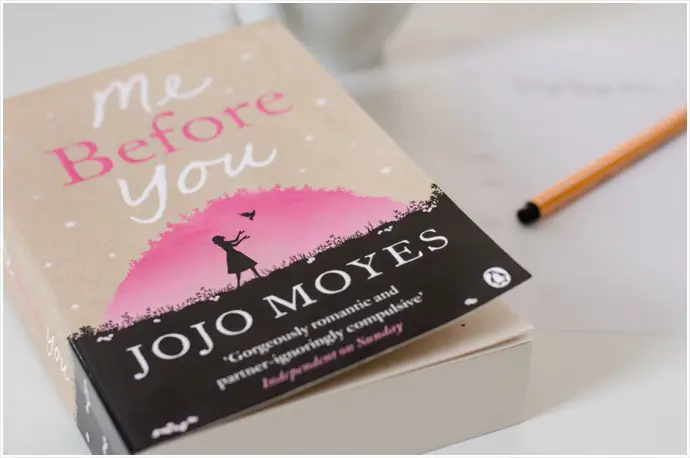

For example, JoJo Moyes’ novel “Me Before You” draws potential readers in with the promise of an unlikely love story between Will, a disabled millionaire, and his physically able caretaker, Louisa. The description on the back of the book reads, “‘Me Before You’ brings to life two people who couldn’t have less in common—a heartbreakingly romantic novel that asks, ‘What do you do when making the person you love happy also means breaking your own heart?’”

What this description doesn’t say, and audiences won’t discover until they are in the midst of reading the novel, is that main character Louisa has actually been hired for glorified suicide-watch, a topic that is troubling and triggering on many levels.

As “Huffington Post” writer Kim Sauder explains, “This is really something a person needs to know, not only to do their job effectively, but also so that they can be aware that the person they work with might self-harm or commit suicide. This is for the benefit of the employee, so they can make an informed decision about whether or not they want to put themselves in a work environment that has the very real potential to be traumatic.”

On top of this, Louisa still lives at home with her parents, dresses abnormally and struggles to enjoy sex because she was gang-raped soon after graduating high school. When asked about why this detail didn’t make it into the film adaptation of the story, author JoJo Moyes states, “You cannot do it as a throwaway.” Yet, in the greater landscape of Will’s struggle to live with his new disability, that is exactly how Louisa’s trauma feels.

As writer Kim Sauder puts it, “It’s bad enough that rape was used as character development, but it is made worse when it is clearly something Louisa is meant to get past with Will’s assistance, but Will isn’t supposed to learn to live with being paralyzed. It clearly sets up the idea that people can and should be expected to come to terms with certain kinds of trauma but not others.” Ultimately, by the end of this novel, audiences are left with unnecessary emotional baggage, all in the name of a promised love story.

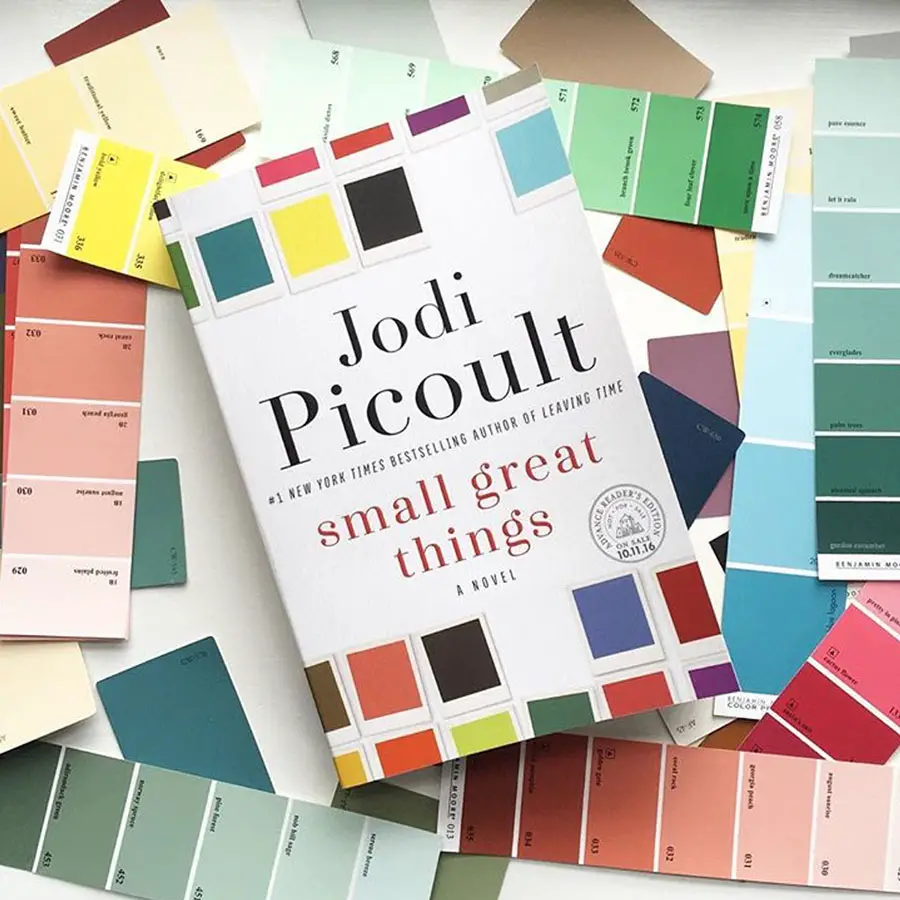

Jodi Picoult’s latest novel, “Small Great Things,” may not hide as extreme or as overwhelming of a subplot, but the book does a great job of promising one thing and achieving another. The back of the book promises a discussion of race relations through the trial of black nurse Ruth Jefferson.

“With incredible empathy, intelligence and candor,” it reads, “Jodi Picoult tackles race, privilege, prejudice, justice and compassion—and doesn’t offer easy answers. ‘Small Great Things’ is a remarkable achievement from a writer at the top of her game.”

It doesn’t mention anywhere in this description that author Jodi Picoult speaks more about her two black protagonists in hyperbolic extremes than as uniquely developed characters. (One is light skinned, the other is dark. One is college educated, the other was a pregnant high-school dropout. One has learned to accept everyday racial snubs, the other has assumed her true African name and hates all white people.)

In fact, the novel ends up developing a more complete and empathetic character in the antagonist, skinhead father Turk Bauer, than in the character of Ruth. As acclaimed feminist Roxane Gay writes in her review, “Picoult certainly seems to have the best of intentions. The question is whether good intentions translate into a good novel…It all starts to feel excessive and desperately didactic.”

So, what is a reader to do? Is it better to live in a world where writers feel free to discuss controversial issues in their literature as a form of dramatic plot movement? Or should readers be fully informed about what they are getting into before they start a book?

Author John Green argues that, “I don’t believe books, even bad books, corrupt us. Instead, I believe books challenge and interrogate. They give us windows into the lives of others, and they give us mirrors so that we can better see ourselves.”

I tend to agree. Even though Moyes’ and Picoult’s books were frustrating for me as a reader, they created a dialogue for two grossly mistreated minority groups. Perhaps, books will someday carry content ratings like movies and TV shows, but for now, before I hit the bookstore, I’ll have to keep refreshing my Good Reads page for an honest reader’s review.