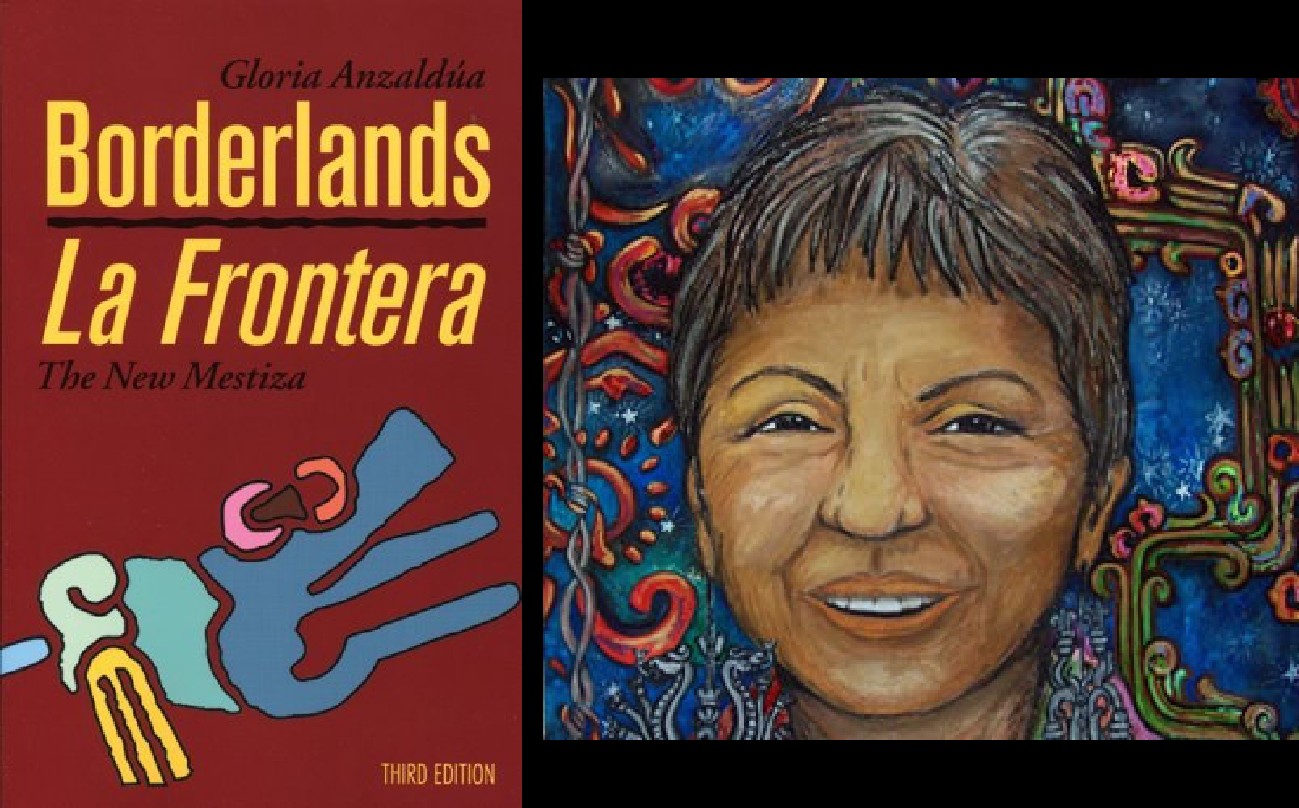

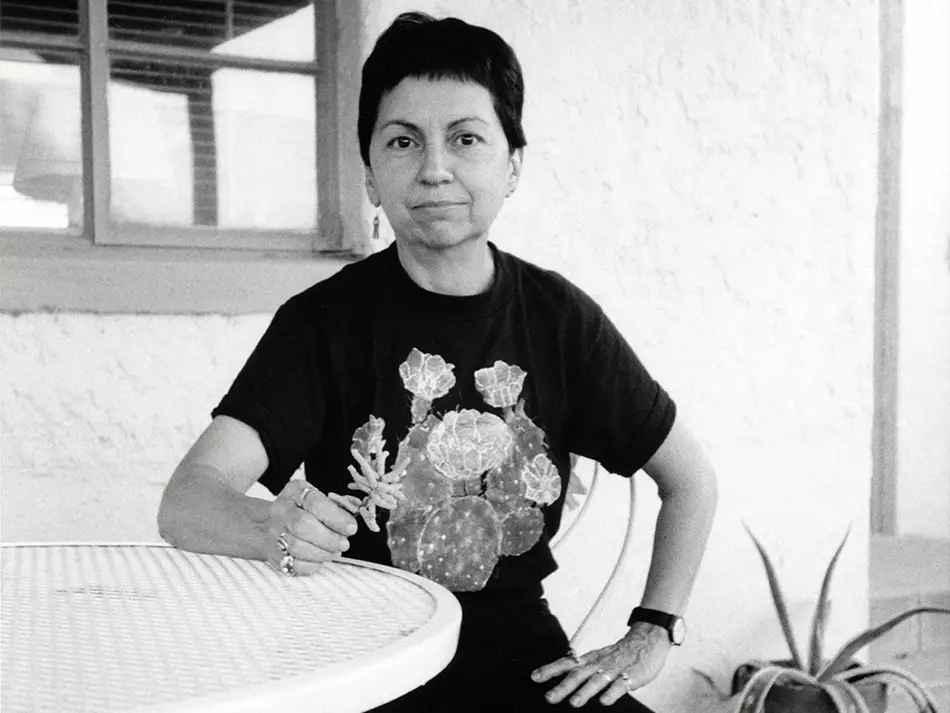

Thirty years ago, Gloria Anzaldúa published the book “Borderlands/ La Frontera” for a world that did not quite yet know what to make of it. It was an unprecedented hybrid of prose and poetry. Through self-reflection, historical research, and cultural awareness, Anzaldúa dissected her own identity as a mestiza living on the southwest border between Texas and Mexico.

She spoke to the sensibilities of simultaneously being Mexican, American and Indigenous, while also making the space for her sexuality as a queer woman.

Even more relevantly, however, she spoke to the need to move past cultural rifts and opposing values. She spoke of the border as “una herida abierta”: an open wound. She was referring to the ways in which different cultures and different nationalities grate against each other, and how the ensuing conflict (not necessarily physical) consumes all those who live on the border.

For her, the border is not only physical, but psychological, sexual and spiritual. It has vastly deep implications for those in its immediate vicinity, but it also extends further, far beyond its physical demarcations, to people on both sides.

The metaphor of an open wound is perfectly fitting to contemporary border discussions. There are families being torn apart. There are more walls being built. The conflict at the border has not diminished since Anzaldúa’s writing. In fact, that wound has gotten bigger. It has been torn further by a renewed anti-immigrant rhetoric. It is bleeding, and one can’t help but feel it.

Make no mistake, what is happening at the border is by design. Border officials are not being forced to separate those families. They are complying with orders, sure, but it is something that is made viable by the acceptance of the border as a real part of our social landscape.

It is justified by the belief that there is a fundamental and irreconcilable difference between America and the rest of the world. And by no means is the U.S. exclusively guilty. But it is currently the focus of our national consciousness, a great shame really, and rightfully it deserves to be scrutinized.

In the book, the main part of Anzaldúa’s prose ends with a chapter titled “La Conciencia de la Mestiza (The conscience of the mestiza), Toward a New Consciousness.” In it, she spoke to progress, to superseding the need for rigid boundaries to define identity. This can be taken and used to critique the current national narrative, which is trying to define itself perfectly rigidly, as a white, Christian nation, with no room for immigrants, or a sensible religious tolerance.

This rhetoric is meant to exclude, and it is exactly what is embodied by the physical border wall. But if there was any confusion in the past, it is now very obvious that the border only serves to cause suffering. It separates, as it’s meant to. Anzaldúa spoke of the pain it caused as a mestiza living in its wake.

But that pain is much more palpable when the news covers kids being torn away from their families. The psychological damage is unfathomable. But it is a natural effect of the border: it separates both physically and psychologically. That was Anzaldúa’s point.

The question is then, beyond pure reaction and protest, how does the nation move forward from this? How can it be ensured that this won’t happen again? Where does one even start? There is a perpetual cycle of violence, between authority and those without, between the oppressor and the oppressed. That cycle needs to be eradicated.

In that final chapter, Anzaldúa provides a timeless insight: “the future depends on the breaking down of paradigms, it depends on the straddling of two or more cultures. By creating a new mythos—that is, a change in the way we perceive reality, the way we see ourselves, and the ways we behave— [we can create] a new consciousness.”

This exhibits one of her core beliefs: we need to move past dualities, we need to move on beyond the oppressor and the oppressed, the “them vs. us.” It only leads to stagnation. It only breeds perpetual violence, perpetual loss, perpetual hurt. It keeps reopening that same psychological wound. It leads to the xenophobia that separates children from their families.

Anzaldúa attributes this mantle of transcendence to the mestiza. For her, the mestiza is someone who, because of her “in-between-ness,” has the capacity to bridge dualities and move beyond them entirely. She can understand and empathize with both Mexican and American (and Indigenous) values. And in doing so, can break the cycle of violence and separation that has plagued the border for centuries.

The thing is, the mestiza can stand in for any conflicted personality. There is no such thing as purity or homogeneity. By the experiences that shape an individual’s life, there is always created something new and “in-between.” And there is always the ability to empathize with others.

We can most definitely empathize with the sanctity of family, of children being kept with their parents. Anzaldúa posited the mestiza as the champion of bringing about “the new consciousness.” But, truthfully, every single person has the capacity and the responsibility to work toward that. It is necessary.

Anzaldúa presents a fitting and conclusive metaphor for the struggle faced on the border — “it is not enough to stand on the opposite river bank, shouting questions, challenging patriarchal white conventions … at some point, on our way to a new consciousness, we will have to leave the opposite bank, the split between the two mortal combatants somehow healed so that we are on both shores at once and, at once, see through serpent and eagle eyes … The possibilities are numerous once we decide to act and not react.”

And that is the call to action. One need not wait for the next great tragedy or debacle. There is no us or them when children are being taken from their parents. That is the result of a worldview that requires borders, that requires arbitrary divisions. That worldview is obsolete, and it must be left behind.