In the past couple months, the rap game has shifted some of its attention toward the subject of mental health: Logic’s pointer to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline “1-800-273-8255” featuring Alessia Cara and Khalid was certified platinum on September 8, Lil Uzi Vert’s upbeat but depressive “XO TOUR Llif3” struck a chord with hundreds of thousands of listeners and XXXTentacion’s reckoning with suicide, “Jocelyn Flores,” took multiple spots on international charts.

Despite the turn toward an open discussion about the gravity of mental health and wellbeing, more young, up-and-coming rappers are being charged with committing the antithesis of healing: abuse. When an artist is a perpetrator of the very actions that evoke the feelings that they lament in their songs, they undermine their message. Abuse in the music industry is nothing new, which makes halting support of abusers all the more important.

A landmark occurrence of domestic violence by an artist came to the front of mainstream media in 2009 when the graphic images of Rihanna’s bruised and bloodied face were released. The story of Chris Brown and Rihanna in the backseat of a car circulated over and over, garnering a lot of sympathy for Rihanna and destroying Brown’s reputation. Brown never fully rehabilitated his image, yet the stain on his career never stopped him from finding fruitful work.

“Yeah 3x” and “Look at Me Now,” singles from his 2011 album “F.A.M.E,” were commercial success and Brown continued to find work performing at award shows and touring. Abusive behavior, it seemed, did not detract from Brown’s skills as a performer. There are multiple other cases like these in the entertainment industry, like Casey Affleck’s 2017 Oscar award, despite the resurgence of two sexual harassment allegations, or Kesha’s ongoing struggle with reportedly abusive former producer Dr. Luke.

Talent appears to quash any concerns about the abusive behavior of a performer, which is especially concerning in the upbringing of the cohort of new hip-hop artists. One of them, Kodak Black, has spent time in jail for possession of drugs and sexual battery. The most disturbing thing he has done, however, was broadcast a sexual encounter with an unnamed woman over Instagram Live—while he was pending a rape charge.

With increased awareness of social media, young artists like Kodak are able to disseminate their lifestyle, ideas and practices easier than ever before. Messages that espouse the objectification of women and show no remorse of prior actions are dangerous to listeners, particularly to impressionable young ones. Currently, Kodak is carrying out a sentence of one year of house arrest, with five years of probation, after being released from jail on June 5.

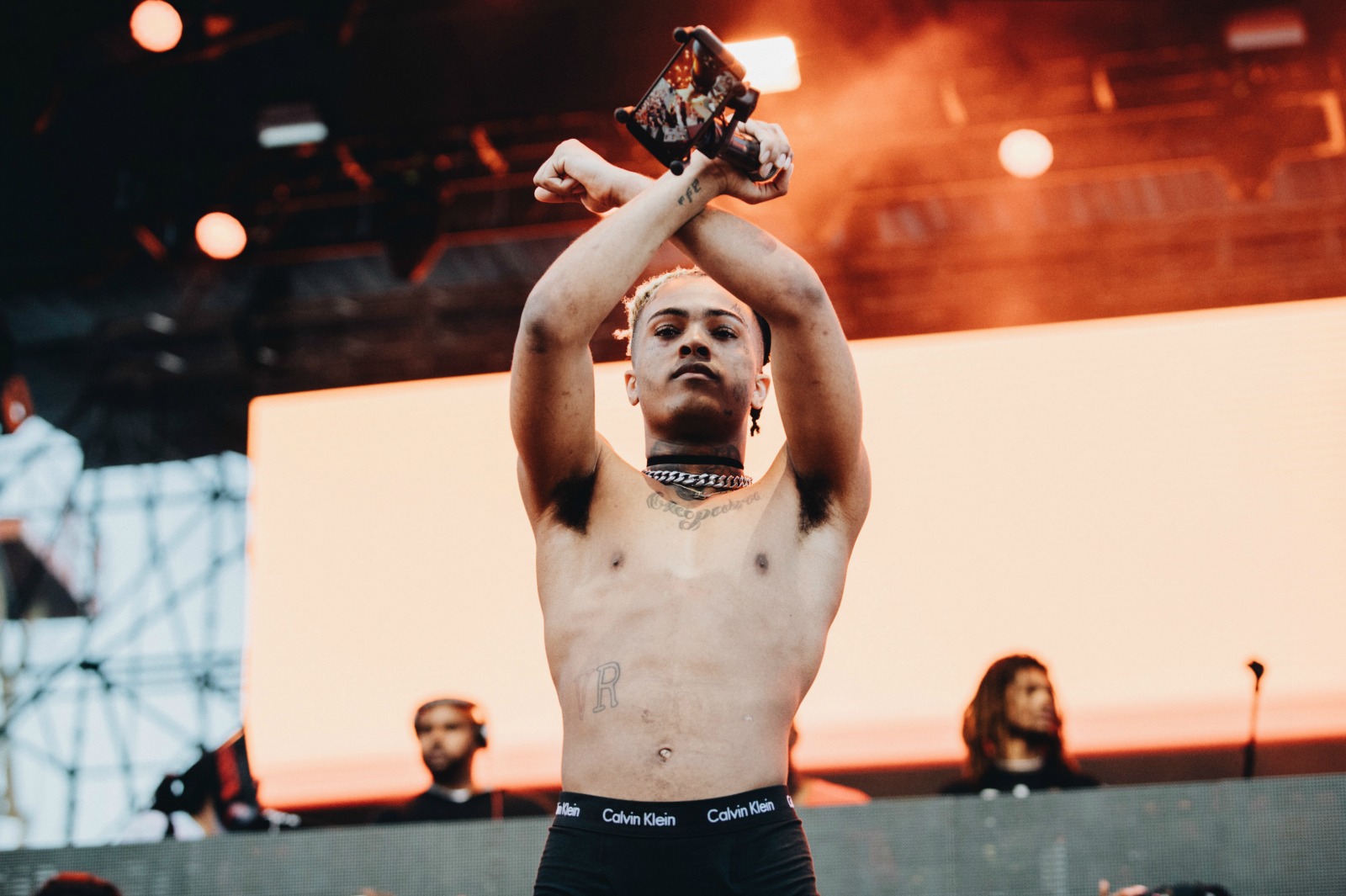

One of Kodak’s contemporaries, XXXTentacion, has been charged with similar counts of domestic abuse. However, XXXTentacion’s actions reflect a deeper, sinister pattern of abuse. Prosecutors have charged the young artist with battery of a pregnant woman, domestic battery, false imprisonment and witness tampering. The victim of XXXTentacion’s abuse states that she moved in with him at his place in North Miami. What follows the cohabitation is a gruesome string of sexual harassment, death threats and physical abuse. Over the course of six months, XXXTentacion threatened to insert a barbecue pitchfork in the victim’s vaginal area, kicked, punched and stomped on her, strangled her on more than one occasion and threatened to kill her and their unborn child. The sadism and manipulation of the rapper’s treatment is incredibly upsetting and warped.

The torture for the victim doesn’t end there, though. After a brutal attack left her with a hemorrhaging eye, she asked to go to a hospital, but instead was taken to a different apartment and left with no phone. The victim was trapped with no exit for two days before finding a way to escape. The pathology of XXXTentacion’s abuse—a false sense of security, control over the body, physical harm and social isolation—are indicators of severe emotional instability. The motivator behind the abuse was primarily jealousy: When the victim gave attention to another man, sexually or otherwise, the young artist would snap.

XXXTentacion’s trial begins on October 5. Over Instagram, XXXTentacion aired his thoughts on the allegations brought against him, leading to a spew of threats of rape and sexual violence: “I’m gonna f— y’all little sisters down their throats, I swear to god. Everyone who called me a domestic abuser, I’m gonna domestically abuse your little sister’s pussy…I think I’m gonna start supporting feminism.”

For the most part, XXXTentacion’s words and actions aren’t preventing any commercial success. His first full-length album, “17,” debuted at number two on the Billboard 200 chart. Early hype and enthusiasm for a full-length release may have spurred first-week sales, but the aftermath of accusations for such a heinous pattern of abuse should have more effect. The disparity between the two begs a few questions: Can artists be separated from the works they create? Or do lifestyles and personalities possess a work of art and blur the lines between the creator and the created?

For some artists, creating a persona to deliver their message is as important as the actual work of art. Some public images, like pop personas (think of the difference between Lady Gaga’s “The Fame” and “Joanne,” or between Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” and “Erotica”), are obviously stylized. The appearance is not genuine or real, and it’s not supposed to be. Other artists like singer-songwriters or those less marketed stand as themselves on the stage. The differences between Lorde’s “Pure Heroine” and “Melodrama,” or between Frank Ocean’s “Channel ORANGE” and “Blonde,” aren’t enormous. Across two albums, both Lorde and Frank Ocean speak ostensibly for themselves. So, if the artist relies on smoke and mirrors, then it is easier to separate the creator from the created. Honesty and confession implicate an artist in their work.

For that reason, XXXTentacion’s connection to his music, which is dark, desolate and often suicidal, cannot be erased. As much as depression can define an aesthetic, the sensation of hopelessness primarily defines a struggle that can feel insurmountable. Those who express their feelings in abusive ways should not be supported, and the best way to do so as a consumer is to stop streaming and buying their music. Is there value in confessional, genre-bending, creatively progressive albums penned by young black artists? Absolutely. But less so when the marks of abuse are so fresh, so pervasive and so public.