Most people today have never heard of the American blues musician David “Junior” Kimbrough, but those who have recognize the impact his music has had on the evolution of rock ’n’ roll and the blues. Kimbrough was born in Hudsonville, Mississippi in 1930 and, although he began playing music early in life, he didn’t discover his own style of the blues until much later. His blues were built from the solemn tunes of his African American ancestors, but as he grew more talented, he expanded upon these roots and evolved his music into a funky groove of his own. He is renowned today in the world of blues as an innovator for his entrancing and irregular use of unstressed and stressed guitar rhythms.

His distinctive style is now known as Hill country blues, characterized by the syncopated hypnotic rhythms he produced. Most of Kimbrough’s music makes use of polyrhythmic elements, a Native African musical technique that refers to the simultaneous use of two or more rhythms that are unique and not derived from one another.

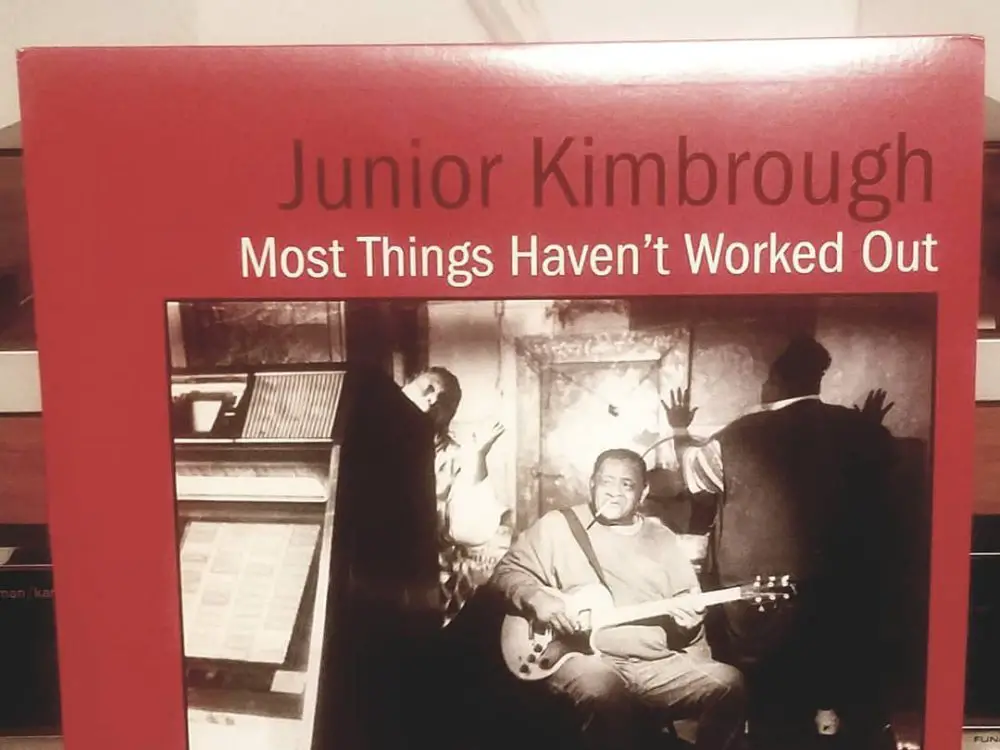

Kimbrough’s novel sound of concurrent reverberating rhythms differentiated him from previous blues musicians, but this originality wasn’t recognized nationally until his later years with the release of his 1992 album, “All Night Long.” Until his death in 1998, Kimbrough operated a juke joint in Chulahoma, Mississippi, where musicians and bands from around the world, including members of U2 and the Rolling Stones, visited to gain inspiration from the artist’s pioneering sounds.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-Taae2zLfA

I was 10 years old when I first heard Junior Kimbrough’s “Feels so Good #2” from his album First Recordings. I was instantly entranced by the fluctuating tone of his shrill voice and the flowing, unpredictable synchronization of his guitar melodies. The lyrics are simple, but the song is anything but. The melodic current Kimbrough produces, with his flowing, twangy guitar and voice that cracks up and down a sliding pitch, sweeps you off your feet and carries you into an erratic river of harmonizing emotion.

Kimbrough’s song “I Gotta Try You Girl” from his 1998 album, “God Knows I Tried,” exemplifies his use of repetitive but heartfelt lyrics. In this song, Kimbrough uses polyrhythmic techniques to blend a fuzzy guitar melody with an electric spur-of-the-moment guitar solo that floats perfectly above his raspy but high pitch voice. If you look plainly at the lyrics, they seem unimpressive, but when you listen to Kimbrough bellow out the verses of this masterpiece, you come to appreciate the meekness of his voice moving subtly between the sharp progressing sound of his melody.

The song “Meet Me in the City” is a blues song that expresses Kimbrough’s longing for a second chance with a girl that has captured his heart. This is the song that ultimately allowed me to respect the blues on a deeper level. Kimbrough’s version entices a flowing emotional state that can only be described by William Wordsworth’s definition of poetry as a “Spontaneous overflow of feelings and emotions recollected in tranquility.”

In the second verse he conveys his attachment toward his love and the oxymoronic state of our emotions: “Sometimes I think I will, baby / and then again my my mind’ll change / It tells me don’t do it no more / Sometimes I think I will.” This verse expresses our mind’s battle between moving on and expressing our love for someone we care for. The ambiguous state of our feelings toward another changes, in order to cope with emotions of self-doubt when the adoration is not mutual.

Throughout this song, Kimbrough’s hypnotic flow takes precedence over the sound of his lyrics, enabling him to prompt a beautiful contrast between his gloomy lyrics that express a pessimistic truth, and a calm flowing melody that reveals hope in his examination of longing.

On the surface, “Meet Me in the City” is a painful cry from Kimbrough to reignite his relationship with a woman he has fallen deeply for once again. Although the lyrics are modest, the rhythm of stressed irregular guitar riffs fills one with unprecedented anticipation, leaving you waiting anxiously to hear what strange sound will come next.

Many blues and rock artists have implemented Kimbrough’s revolutionary style of Hill country blues into their music, but none have done it better than the indie rock band The Black Keys. I give credit to The Black Keys for first introducing me to this blues legend through their album “Chulahoma,” in which they covered six of Kimbrough’s masterpieces including “Meet Me in the City.” As soon as I heard this album, I embarked on a Kimbrough research journey, listening to all his music in a matter of a few days.

Although the Black Keys version of “Meet Me in the City” embodies Kimbrough’s vision of the blues exquisitely, the band intensifies their pronunciation of his lyrics and linger offbeat with swells of dissonant guitar, cleaning up the original while still maintaining the eccentricity of his unconventional guitar riffs. The lyrics in the version produced by The Black Keys don’t provide as much in-depth emotion as Kimbrough’s, but the implementation of their original guitar and drum solo’s shows that they understood this style of the blues better than anyone else. I remain dead set in my opinion that no other artist has replicated the style and groove of Kimbrough with such accuracy as The Black Keys.

Kimbrough wasn’t appreciated or widely known until he was 60 years old, but his musical legacy continues to live on through the musicians inspired by his unique style of the blues. His attempt to move away from the generic blues sound of his day was a push toward his individual vision and produced a long line of musical outliers that sought to imitate his eccentricity. His independent sound thrusts listeners into a trance, allowing them to experience his “spontaneous overflow of feelings and emotions recollected in tranquility.” Because of his unique, hypnotic approach to the blues, his music has the remarkable ability to fuse your mental state with his, evoking a deep sentiment like none other.