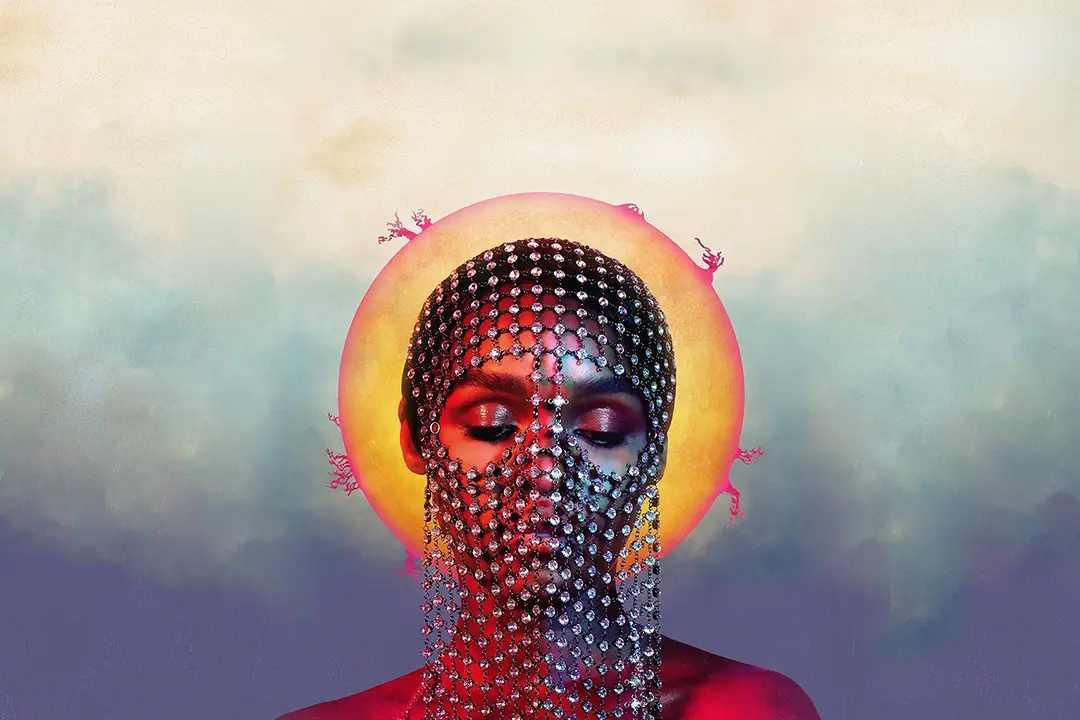

Janelle Monáe has always been a profoundly political artist. You don’t, after all, make an EP and two concept albums set in an Afro-futuristic dystopia where the oppression of androids is used as an extended metaphor for the oppression of black and LGBTQ+ people without being political. Her latest album, “Dirty Computer,” is her most pointed yet — specifically because Monáe brings so much of her own experience into it.

This time, instead of taking on the persona of an android, Monáe’s flesh and blood album protagonist Jane 57821 grapples head-on with the issues that affect Monáe as a queer black woman.

On April 26, 2018, the word “pansexual” was one of the top words looked up on Merriam-Webster’s website. Why? After years of speculation, one day before the release of her new album, Janelle Monáe had just come out publicly in an article for Rolling Stone.

Monáe had long been the recipient of questions about her sexuality, fueled by the sexual ambiguity of her early albums. Her stock answer, “I only date androids,” was a tongue-in-cheek reply — but the clues to her sexuality lay in her music.

There has always been a queer undercurrent in Monáe’s music. The song “Mushrooms and Roses” from her 2010 album, “The ArchAndroid,” mentions a love interest named Mary; the song “Q.U.E.E.N.” off of 2013’s “The Electric Lady” also mentions Mary and was originally titled “Q.U.E.E.R.” — a word that can still be heard in the background vocals of the chorus.

The song “Sally Ride,” too, pays homage in its title to the first known LGBTQ+ astronaut. Rarely, though, did Monáe mention queer sexuality explicitly in the previous albums. It was always a subtle detail in her music — that is, until the arrival of “Dirty Computer.”

Although Rolling Stone may have been Monáe’s official public coming-out, Monáe’s release of several music videos for her singles that just preceded the article were her actual coming-out.

Even the most confused, in-denial straight people could see that whatever is going on between Monáe and Tessa Thompson in the music videos is far from “just gals being pals”: If Monáe dancing between Tessa Thompson and Jayson Aaron in “Make Me Feel” wasn’t enough, surely the pussy pants from “PYNK” would have set off that lightbulb.

“Dirty Computer” places black queer womanhood at its forefront. Monáe’s personal and political expressions are out in full force in the new album. While the previous two albums, also set in Afro-futuristic dystopias, focused on Cindi Mayweather, the “chosen android” meant to liberate the world, this one follows the human Jane 57821, the eponymous “Dirty Computer.”

Monáe’s shift from the perspective of the Archandroid/Electric Lady to the Dirty Computer is a significant one, but not an irreconcilable one. While Monáe previously explored her identity as a queer woman of color through the metaphor of oppressed androids in a dystopian-surveillance state, here she more or less sheds the mask of the android, giving her the freedom to openly celebrate her identity and shed light on the difficulties she faces.

“Dirty Computer” is Monáe at her most unapologetically black and queer. The album opener, “Dirty Computer,” quietly harmonized by none other than Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, serves as a jumping-off point for what it is to be marginalized, or to be labelled a “dirty computer.”

It is a lament, of sorts, but also an acceptance: “Cause baby, all I’ll ever be / Is your dirty computer,” Monáe slowly intones. From there, Monáe pushes you in headfirst — calling out police brutality and the surveillance state that specifically targets black people, countering the perception that to be queer is to be abnormal or somehow monstrous and warning certain people who need a warning that “this pussy grabs back.”

The album is dripping with sex, too — which is particularly important, given that queer people are rarely represented as actual sexual beings in media without being demonized.

When Monáe sings of being “Young, black, wild and free / Naked in the limousine” and insists that “I am not America’s nightmare, I am the American dream” in “Crazy, Classic, Life,” she reclaims sex for queer black women — and redefines what it is to be American.

This sex-positivity is further seen in the ’80s-sounding “Take a Byte” and “Make Me Feel,” (in which the influence of Monáe’s late mentor and fellow gender-norm-defying artist, Prince, can be felt), as well as in the Zoë Kravitz-backed “Screwed,” “PYNK,” which features Grimes (and the notorious pussy pants) and “I Got the Juice,” which features Pharrell.

Monáe is both vulnerable and celebratory, often at the same time — on the (fire!) track “Django Jane,” she spits rhymes calling out the people who called her “too mannish” and shouting out “black girl magic.”

It is this celebratory vulnerability that gives “Dirty Computer” its power. By speaking directly and openly about her experience, Monáe is able, at long last, to use her art as a powerful tool.

The world may be telling queer black women that they should hide those parts of themselves that do not conform, but through “Dirty Computer,” Monáe has unleashed those forbidden emotions into a profoundly political, radically black and queer piece of art.