Have you ever seen a piece of graffiti that left you wondering, “How the hell did they get up there?!” Street art has captivated society since the late 60s for multiple reasons, ranging from the kooky places they’re located to the social protest present in the tag. While some might be quick to harshly condemn graffiti as ugly vandalism, there are artists who are using their craft to draw attention to social issues that plague communities. If you’re anything like me, someone with laughable artistic skills, then you’ll appreciate the wild artists who prefer an unconventional canvas.

To many, graffiti can be seen as a huge eyesore and is sometimes linked to impoverished neighborhoods and failing businesses. But what if we take a step back and readjust the lenses that we view graffiti through? Street art is gnarly work that can ignite social change, so why not learn to value it appropriately? Artists who are creating projects in the street have begun to redefine the very basis of what graffiti and street art means to the general public.

In the 60s, graffiti in public spaces took off with Philly-native Darryl McCray at the forefront. McCray, better known by his street name Cornbread, is considered one of the pioneers of public drawings. Cornbread’s penchant for tagging all over the city of brotherly love was a source of inspiration for others all over the country to begin to take to the streets armed with art tools. Some artists still utilize the good ole’ can of spray paint, while others are taking a more formal approach to their urban creations. While the style that each artist chooses varies, the same question still begs to be asked: Can social awareness grow through the very public forum of graffiti?

Keith Haring

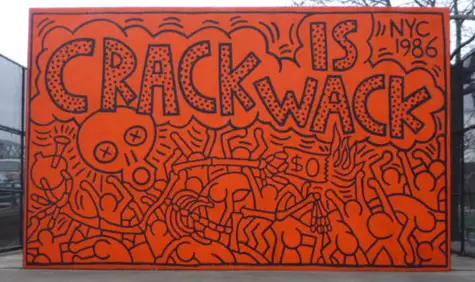

The late Keith Haring utilized public space to create a conversation about issues in society that he believed were of critical importance. Haring’s installations can be found all over the world, but some of my favorite works of Haring reside in the concrete jungle of New York City. One of Haring’s most notable works of public art is his “Crack is Wack” mural that is tagged on an enormous handball court that sits adjacent to the Harlem River Drive in New York City. The artistic creation, completed by Haring in 1986, addresses the devastating crack epidemic that ran rampant through the city in the late 80s to early 90s.

Haring’s mural stands as a cautionary tale to the youth of the city, warning about the life-threatening effects of the highly addictive drug. A cool facet of Haring’s work is that at the time of its creation the artist hadn’t received any go-ahead from the city—it was graffiti in its most primal form. As the mural gained notoriety, the city then protected the wall of art and it still stands today in clear view from the Harlem River Drive. Haring’s work is a true testament to the notion that artists who specialize in public tagging will go to extreme lengths to spread their message.

Drugs were not the only topic that Haring ferociously waged war on. As someone that lived and eventually died from AIDS, Haring created various public installations that brought the then-taboo topic to the forefront of conversation. Haring traveled to the Raval neighborhood in Barcelona to create a very personal and public mural named “Together We Can Stop AIDS.” At the time, AIDS was a topic in Barcelona that most people generally avoided, and those infected with the disease were basically treated like lepers.

Haring, having only been diagnosed with HIV one year prior, decided to meet the virus head-on and devoted a good chunk of his career to creating works that addressed the detrimental, biological and social effects of HIV/AIDS. The mural that Haring created in Barcelona reaffirms the necessity for graffiti and street art; Haring’s naming of the art piece raised awareness and let others know that living with AIDS didn’t have to mean that you were a social outcast. Haring’s stick figure-esque drawings are easily recognizable (they even appear on some cringe-worthy forever-21 tees), so it is safe to say that the gifted artist left the mark he had hoped for.

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, like Haring, hones her artistic craft in public spaces to make a statement about societal issues. Residing in Brooklyn, New York, Fazlalizadeh is making quite the splash in the realm of street art. The Oklahoma native has created a powerful series addressing gender-based harassment that happens far too often in society. Fazlalizadeh created “Stop Telling Women to Smile” by sitting down with various women who have experienced street harassment and turned their own stories and experiences into socially progressive street art. The portraits are large in size and stature, demanding the viewer’s utmost attention be paid to them. Underneath the portraits are various phrases, such as “Harassing women does not prove your masculinity” and “I am not here for you.” These phrases are meant to reaffirm women’s position of power and their right to exist in the public sphere devoid of harassment.

By using buildings and other structures as a medium, the socially motivated artist is creating art right in the heart of where a bulk of harassment happens: the streets. It’s fascinating to examine the ways that harassment and public space are juxtaposed, and hopefully, the art reaches the level-five freaks who feel the need to catcall women.

Fazlalizadeh’s art is commendable because she creates her art with the goal to reach as many people as possible. For example, some of the phrases written underneath the portraits are tagged in Spanish, recognizing non-English speaking women affected by harassment. Fazlalizadeh’s commitment to representation in her urban murals addresses the high number (65 percent) of women who are affected by harassment, and her work reflects the basic fact of sexual harassment: it affects all kinds of women.

Fazlalizadeh, in collaboration with Fusion Digital, took to the streets of Mexico City with a project titled “All The Time. Every Day.” The new series essentially functions as an extension of “Stop Telling Women to Smile” and the goal of the project is to bring light to the inequity women face in the streets of Mexico. “Stop Telling Women To Smile” and “All The Time. Every Day.” are vehicles of social change because they exist in a very public space; and by doing so, the works of art create a conversation about why street harassment is problematic and what can be done to combat the issue. And just a general rule of thumb, if you feel the desire to comment on a woman’s outfit/smile/whatever, just don’t.

Social change is a necessary element for any community to grow. Writing graffiti off as vandalism or a blemish within a society works to delegitimize a very real agent of social awareness. The next time you see art tagged on a building or bridge, try to identify what message the graffiti could be trying to convey rather than just shrugging it off.