Is Cuba Celebrating or Mourning?

After the death of their dictator, I sat down with some Cuban friends to learn how they felt about the end of an era.

By Molly Flynn, University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Last Monday, I sat around a round wooden table with two Cubans and one gringo.

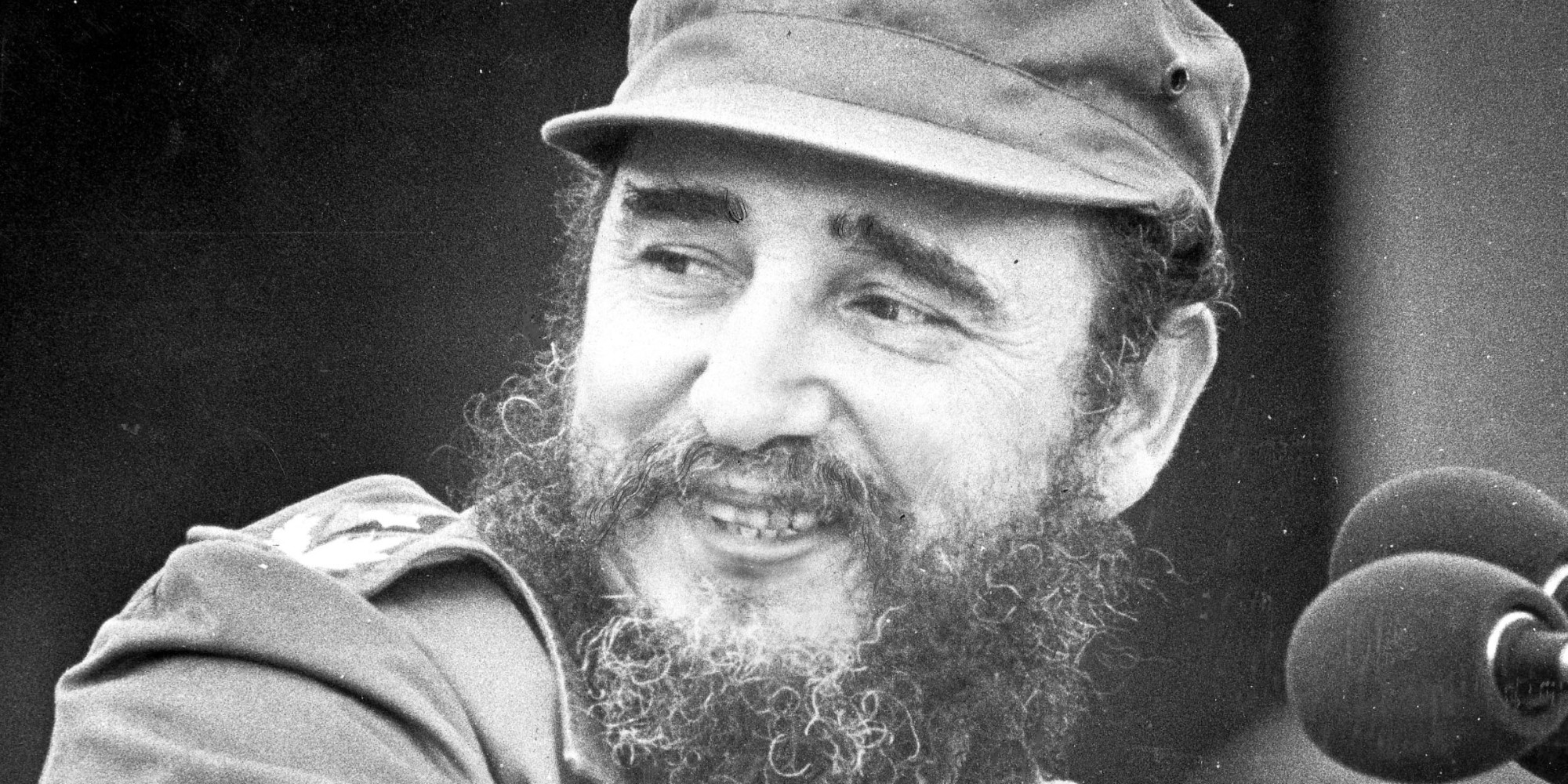

The sun began to set as we ate Cuban sandwiches and sipped on Cuba Libres. The yucca frita and congrí decorated the table as the four of us gathered not only to celebrate Cuba, but also to commemorate something else. Each of us, with glasses full of rum and Coke, drank to celebrate and to mourn the death of one of the longest living dictators in history: Fidel Castro. Monday night, only a few days after his passing, I was able to sit and soak in the differentiating views and reactions to the death of el Líder Máximo from three people who had spent a large chunk of time on the island.

While the table was diversified with typical Cuban dishes, it was also sprinkled with contrasting views and reactions regarding Castro’s death. The two Cubans, Amittay and Oscar, sat on either side of each other and served as a juxtaposition of views while the gringo, Rusty, sat in between them. Although all three of these men share a love for the island, not everyone shares an equal love for el Comandante.

My father is the gringo that I sat next to. When he was a young man, he discovered a passion for the Latin people—specifically the Cubans. Through incredible circumstances, Rusty was able to overcome obstacles that stood in his way to arrive to the island. Now, over twenty years since his start with his interactions in Cuba, after donating hundreds of millions of medical supplies to the Cuban people, and after exposing his family to a world much different than our own, my father sat next to two friends he made along the way to discuss a moment in history that will forever be iconic for the Cuban people.

I wanted to spend some time with Cubans discussing this topic because, while I spent 12 years of my childhood traveling back and forth to Cuba with my dad, I can never truly claim to be Cubana. At the end of the day, I am an American and—no matter how hard I try—I cannot think about Castro’s death while fully separating my American thought processes. I can tell you that my family and I celebrated the news while recognizing that, for over 60 years, Castro led with propaganda and fear, but I can’t tell you that we celebrated from a purely Cuban perspective. I celebrated because I knew that many of my Cuban friends had risked their lives by boarding homemade rafts to escape oppression and persecution. While Miami is only 90 miles from Cuba, the journey by raft seems like a lifetime. Sharks, storms and the Coast Guard are only a small portion of the dangers that face a fleeing Cuban. So while my celebration was partially American, it was mainly out of empathy for my Cuban family.

On Monday night, the four of us talked about memories that we had about our time together in Cuba. I remembered, as a kid, when we would travel to Cuba for “medical” purposes but really to visit our fellow church, we would have to worship underground and pray that the CDR—Committee for the Defense of the Revolution—would not interrupt and intervene. My Christian friends were forced to swear allegiance to Castro and many pastors were incarcerated or sent to internment camps solely because they pledged loyalty to a higher power. Amittay’s father was among those sent to the camps. But, to the communist government, any declaration or praise to someone other than Castro was seen as blasphemy—Castro was the only higher power. Oscar contributed to these memories and reminded us that the Cubans are not communists, they are Fidelists.

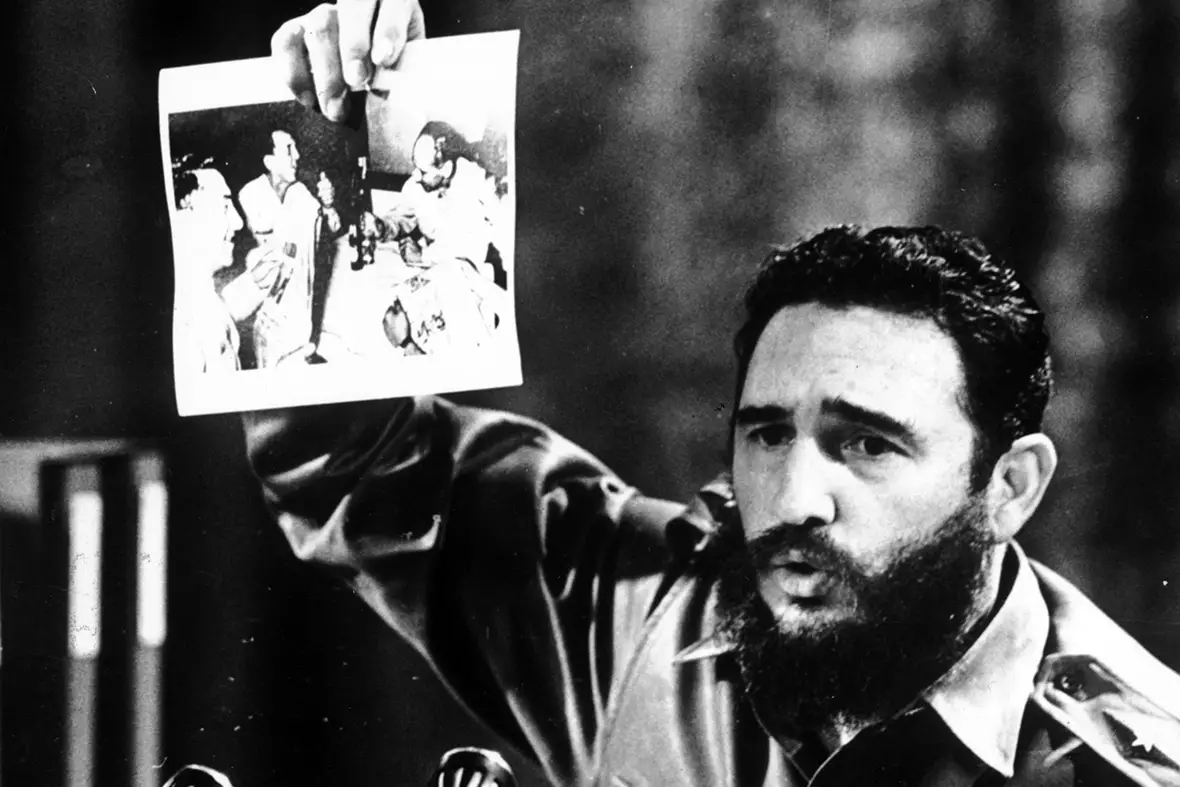

I remember how my friends, in reference to Castro, would use their hands to outline the figure of a beard on their faces. The censorship of speech on the island forced the Cubans to use ambiguous symbols and code words to express their true sentiments. The people dared not to say his name or to speak ill of him. They feared he had spies everywhere. Even in the wake of his death, there is still lingering fear. Monday night, after half of the sandwiches were gone, Oscar spoke specifically of this fear.

While Oscar has made it to the United States, his son is still in Cuba. As we sat together, he received text messages from his son; he said that all the television channels were off, that the police were marching the streets and that no one dared to leave their homes. If there were ever a time for a new revolution, the time would be now, so out of fear and out of desire to clutch onto a fleeting absolute power with the death of the figure head, Cuban governmental forces marched the streets to remind the public that el poder del Líder continuará—the Leader’s power will continue. But even in the continuing presence of fear, there is a newfound hope that has not been present in Cuba for years.

As the conversation evolved from reminiscing on moments spent together on the island to realizing the weight of the new reality, Rusty made an interesting claim, “Everyone loves Fidel and everyone hates Fidel.” Amittay winced at this statement. He shook his head in defiance claiming that he was not among the loyalists. Oscar on the other hand, who has recently fled Cuba and is now a U.S. resident, claimed the opposite—his loyalty still chained to a government that has told him for his entire life that Castro is paramount and that the Cuban government is superior to all else. For him, it is difficult to separate the love of his country from the love of Castro. Still, he drank with us and cheered with us.

But even Amittay, who for years was persecuted for his connection to my father and to the Christian church, understood Castro’s genius. “He was a smart son of a bitch,” he said in his Cuban accent, which only became thicker with each shot of rum he drank. He spoke about Castro’s ability to romanticize the public. Even Amittay’s mother, who was a strong Christian and was also persecuted for her faith, would run to the streets during presidential marches just to catch a glimpse of the Savior of Cuba. “Only an intelligent man could turn the people he oppressed into the people who praised him,” Amittay said with bereavement over his broken country.

As the bottle of rum began to empty, the conversation turned from reminiscing the past to hypothesizing the future. Que será a Cuba? What will happen to Cuba? Amittay believes there will be drastic change in the next few years. He hopes that with the passing of the Oppressor, freedom will begin to seep into a country whose borders have been shut through protectionist policies for years. Oscar thinks the revolution will continue for a while, and then maybe, there will be change. Rusty shares similar views to Amittay but believes in a more realistic timeframe.

I am not quite sure what I believe, but I can tell you what I hope for. I hope that as the Cuban people are separated from the figure of Castro, they will become empowered and will once again fight for la gente—the common people. I hope that culture is preserved as America begins to reenter a country that has been off-limits to gringos for years. I hope that one day, I can return to the island that raised me and speak as freely about the future there as I can here on a Monday night, with sweet drinks and even sweeter friends.

And as we swallowed the final sips of rum with the adjournment of the night, we each said goodbye with a kiss on the cheek in typical Cuban fashion.