If someone asked you to name people with iconic hair, who would you think of? I bet the last person to come to mind would be a founding father of the country, George Washington.

Considered the most researched mane of hair, Washington’s locks were recently found in a 1793 almanac in Union College library. Considered to be now the 16th known lock of Washington’s hair (there have been hundreds of unverified reports of ownership), the lock now constitutes a rare piece of history.

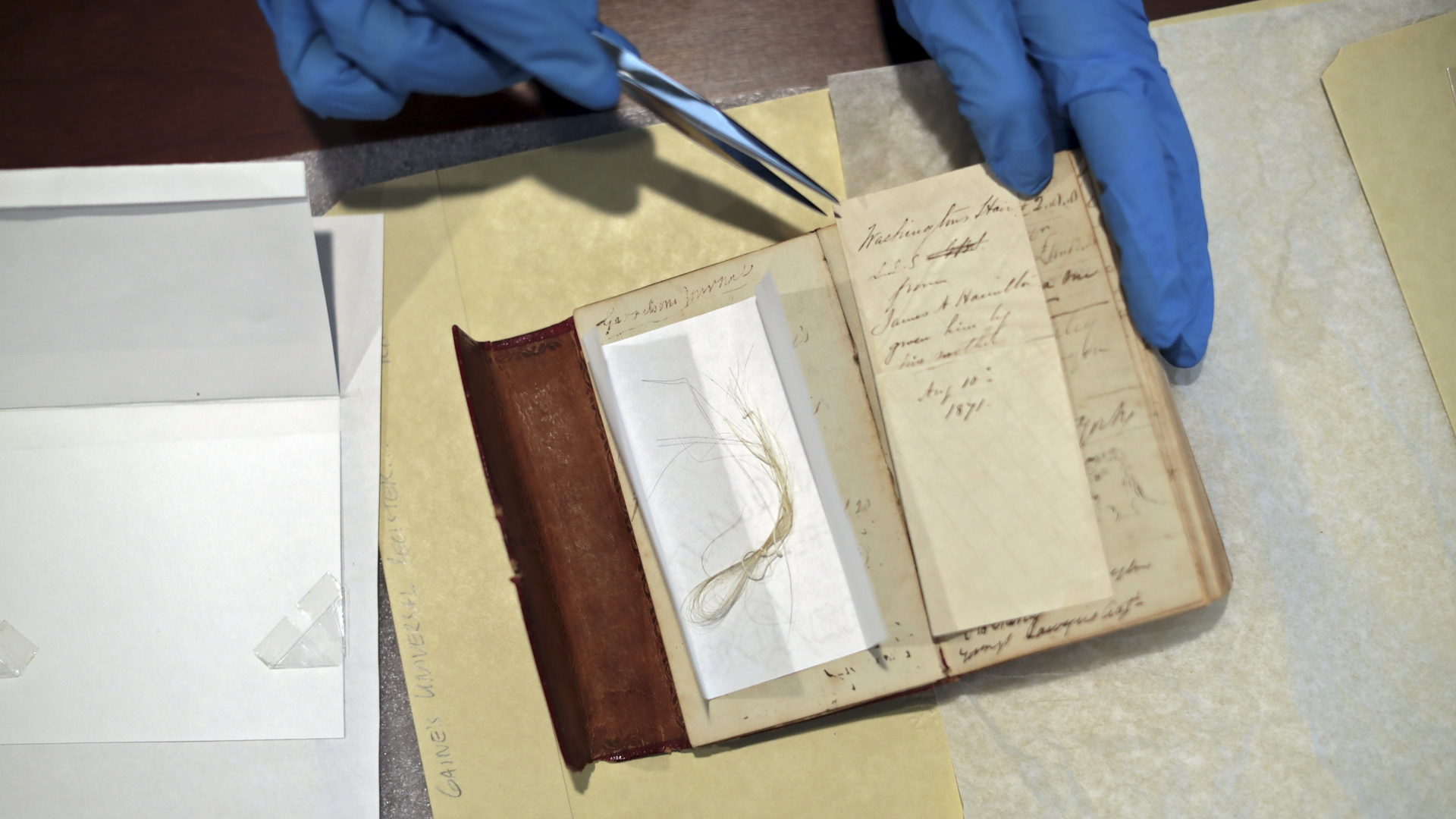

Librarian John Myers noticed the seemingly untouched copy of “Gaines Universal Register” and sifted through its contents — like any normal day as a catalogue librarian.

Between the old brittle pages were letters from the book’s original owner and an envelope with “Washington’s Hair” scrolled across its surface. Myers unlocked a piece of the past at that very moment, sparking a spike in interest in the symbolic founder of the United States.

Though its discovery in a book might be unusual, hair has been used a historical archive for centuries and is most commonly found woven into clothing and jewelry.

Rather than elicit looks of disgust, walking around with someone’s hair on your person was generally met with appreciation, as the symbolism behind the gesture made keeping a pocketed lock somewhat commonplace throughout history.

During the Victorian era, lovers exchanged a lock of hair as mementos of their affection, the idea being that even though they were apart, the hirsute trinkets metaphorically connected them. In other eras, jewelry is interwoven with hair to symbolize sexuality and romantic attachment toward someone.

Receiving hair from a significant other, deceased friend or relative connected the receiver to the owner on a deeper level, in much the same way that you might carry a photo in your wallet or have a picture of someone as your cellphone’s background.

Indeed, the history of hair itself is a rich one, as its styles, fads, accessories, decorations and more have always intimately reflected time periods and their social norms. So, though finding a hidden package of hair may seem irrelevant to the casual discoverer, historians could tell you that underneath all of the hairspray, gel, mousse and curling irons, the follicles have an amazing story to tell.

The way hair has been styled, worn and symbolized has changed throughout the years, but one thing has stayed the same: hair will always hold meaning. George Washington’s hair is no different and the stylistically coiled white hair on the dollar bill is far from the truth. Washington did not have white hair until his presidency had started to end.

Washington was actually a natural redhead with some brown mixed in and powdering hair was the trend of the time period. Just like today’s trends, where some young men put gel in their hair, Washington would powder his hair to give the appearance of having white locks. His coiled hair was his, despite myths that have claimed his hair was, instead, an elaborate wig.

Like other men in authority, Washington followed a particular hairstyle that was similarly worn by the Brits, and this hair routine was a tedious process. He added volume to his hair, accessorized his ponytail with a ribbon, rarely shampooed and used grease as a conditioner to perfect his mane.

To have even a small snippet of Washington’s hair is a historically significant achievement for Union College; the strands truly show the connection Washington had to the college.

Union College’s archives have collaborated with Schuyler Mansion to determine the origin of how Washington’s lock of hair was stored in the almanac. Owned by Philip J. Schuyler, the almanac was unknown to the college until Myers discovery.

The neatly tied lock of hair holds a majorly significant historical footprint in Union College. Opened in 1795 — four years before the death of Washington — the college located in Schenectady, New York was founded by General Philip Schuyler and Schuyler’s grandson, James Alexander Hamilton, whose father was the famous Alexander Hamilton. History has shown that Hamilton and Washington worked closely together.

According to Union College’s theory, Philip J. Schuyler must have received parts of Washington’s hair as a memento from James Hamilton, who received the hair from Martha Washington.

Archivists believe that another lock of hair that was found in Massachusetts Historical Society is linked. DNA testing would be the best way to fully determine if the bundle of hair is actually Washington’s.

The major problem? Hair that is over two hundred years old would most likely have little to no DNA. If hair does has DNA on it, there is a risk that the strands themselves can be destroyed in the process of determining authenticity. Historians and archivists also look for authenticity through other means of evidence, though.

Like a lawyer, research done by historians and archivists is collected and examined to find if an item, era of history or person truly existed, fully relying on historical content (instead of science) to determine accuracy. Without science, some people might not believe that the locks found are actually Washington’s.

In Massachusetts strands of Washington’s hair were stored in a golden locket and sewn into a piece of fabric. By comparing handwritings that were both found with the strands of hair, it has been concluded that the samples are authentic.

Who knew that Washington’s hair could travel that far?

George Washington is a symbolic figure of America and with attention being drawn to Union College, the centuries-old hair has re-sparked an interest in American history for many.

As Union College is preparing to have the hair carefully displayed, hopefully preserving it better than between the pages of “Gaines Universal Register,” the man who defines this nation can be honored even more.