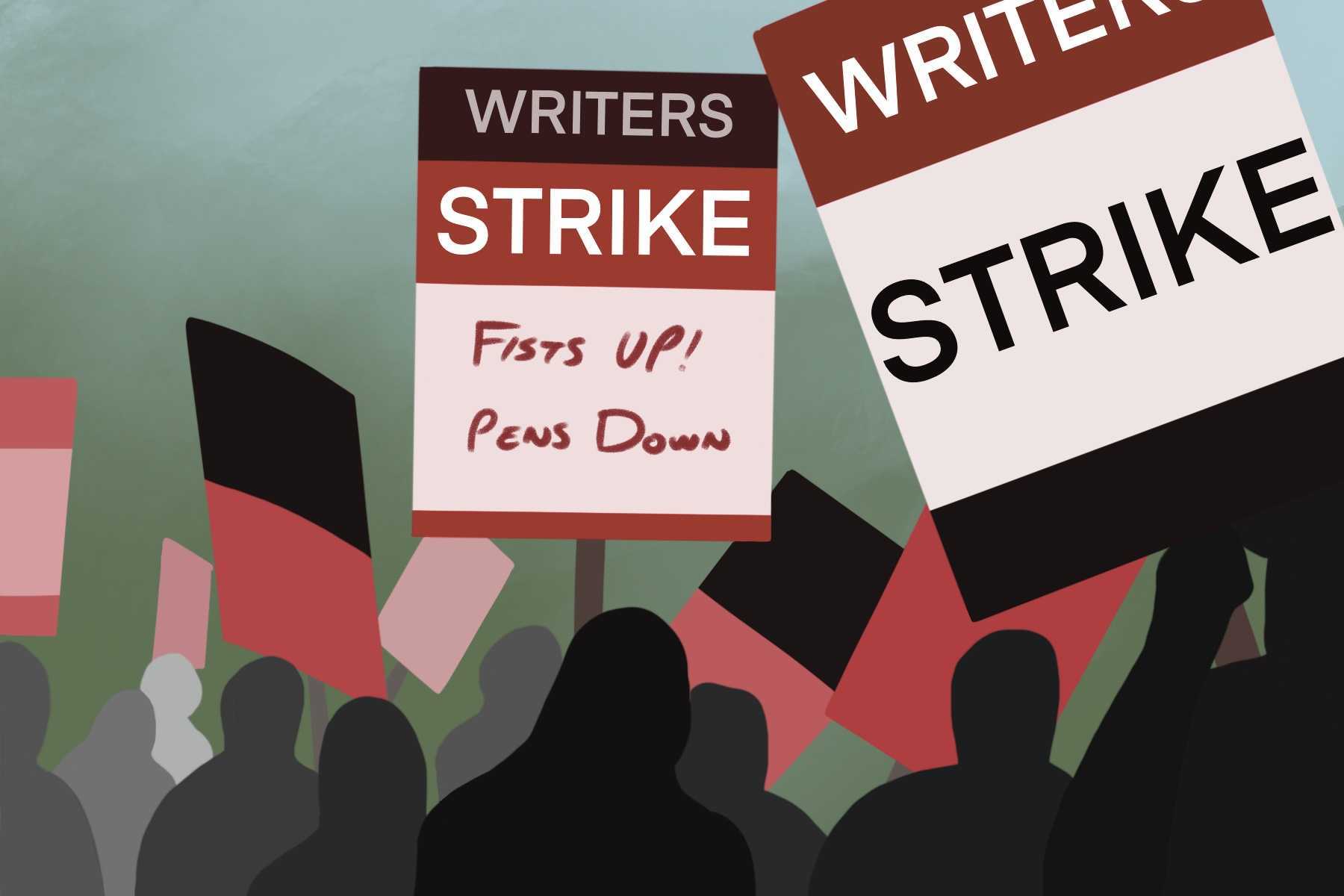

For the past year, the American film and television industry has been bracing for a writers’ strike, and it finally hit. On May 2, 2023, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) went on strike after weeks of unfruitful negotiations with major studios over compensation and career development practices. This means that most American screenwriters won’t be writing or selling scripts for the foreseeable future. Viewers at home are wondering how this will affect their favorite shows and movies. So, what exactly is the conflict between the WGA and the studios, and what can we expect on our screens?

The WGA is a coalition of two labor unions, WGA East (headquartered in New York City) and WGA West (headquartered in Los Angeles), that represent members who write for movies, TV shows and news. The Guild “negotiates…contracts that protect the creative and economic rights of its members, conducts programs…on issues of interest to writers, and presents writers’ views to various bodies of government.” In a country where union membership has dwindled to just 10.1% as of January 2023, the film/TV industry is one of the only sectors wherein the vast majority of workers hold union membership. Similar organizations exist for actors, producers and directors.

Up until the 2010s, screenwriting functioned like a normal career. Screenwriters got staffed on shows with 20+ episode seasons that were either in pre-production (writing), production (filming, which often requires rewrites) or post-production (editing and distribution) for most of the year. This meant long contracts with studios, which guaranteed employment and insurance coverage for a longer period. Network syndication was also a huge moneymaker. Writers earned residuals from commercials that aired when episodes they wrote re-ran on TV. Film writers were also able to sell screenplays for competitive prices.

Since the advent of streaming, screenwriting has drastically changed. Comedy writer Michael Jamin explained the situation in an article for The Guardian: “Despite that fact that there seem to be more shows than ever, television writing staffs have decreased in size; so has the average term of employment. Most writers get paid per episode produced. Years ago, if you were writing on a hit show, you’d produce 22 or even 24 episodes a season. Then you’d take a short hiatus and do it again. Today, if you’re on a hit show you’re lucky to produce eight or 10 episodes a season.” Because of the sheer number of shows, streamers can space out seasons, meaning that writers are constantly scrambling to get staffed on multiple shows. Filming also occurs months or even years after writing, meaning that young writers rarely get chances to go on set. This makes it much harder for them to climb up the ladder to produce their own episodes and become showrunners. As a result, screenwriting is starting to feel more like a gig economy than a stable career. When Emmy-award-winning writers are still working minimum-wage service jobs to stay afloat, you know there’s a problem.

In a March 2023 report entitled “Writers Are Not Keeping Up,” the WGA outlined these concerns. Accounting for inflation, the median weekly pay for writer-producers has declined 23% over the past decade. Artificial intelligence (AI) is also a worry, especially considering that AI programs have already been caught stealing work from visual artists. Writers are advocating for a total ban on AI-generated scripts and edits in order to protect their intellectual property, their creative visions and their jobs.

The WGA brought these concerns up in recent triennial contract negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) which includes Warner Brothers Discovery, Amazon, Netflix, NBC Universal, Disney, Apple, Paramount and Sony. Unfortunately, the studios were unwilling to even consider many of the union’s proposals. “The companies’…immovable stance…[shows] a commitment to further devaluing the profession of writing,” WGA East stated in a press release. On May 1, WGA members in LA and NYC began picketing in front of studio headquarters.

This conflict draws comparisons to the last WGA strike. Since the genesis of the union in 1954, media innovations have driven industrial action. During the 2007-2008 television season, the WGA halted writing for 100 days because members weren’t receiving equitable residual compensation for DVD, VOD (video on-demand) and new media (i.e., iTunes) sales. The strike transformed the industry. Shows from “Desperate Housewives” to “Gossip Girl” had shorter seasons that year. On some projects, writers had to rush to finish scripts before the strike, leaving “Heroes” and the James Bond flick “Quantum of Solace” with flimsy plots that tanked their commercial appeal. “Pushing Daisies” is one of many fan favorites that was canceled altogether. In the vacuum, networks pivoted to unscripted reality series. “Big Brother,” “The Amazing Race,” and “The Apprentice” got renewed because of the WGA strike. Over 14 weeks, the union cost the Los Angeles economy an estimated $2 billion including their own lost wages. In the end, their sacrifice paid off — they won increased residuals for new media distribution.

This year, they’re hoping to replicate that success. Paramount Global CEO Bob Bakish assured investors on a May 4 earnings call that “consumers really won’t notice anything for a while,” citing the studio’s reality programs, sports broadcasts and massive library of banked scripted content. Executives across the industry have echoed this sentiment. However, the numbers tell a different story. This WGA strike is already projected to cost Los Angeles more than the last one. Nationally, studios lost over $10 billion in valuation in less than one week after the first day of the strike. In terms of production, late-night comedy shows face the most immediate impact. “Saturday Night Live” “Late Night with Seth Meyers,” “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” and “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” shut down in the first week of May. NBC and CBS are showing reruns in their time slots. Hit dramas like “Stranger Things,” “Yellowjackets,” the upcoming “Game of Thrones” prequel and the Marvel “Blade” film are also on pause.

Some productions with finished scripts are powering through. These include “Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power” and “The Last of Us.” It’s a plus for fans, but it also ignores that writing continues during production. Sometimes lines or entire arcs need to be reworked, and shooting without writers risks a final product riddled with haphazard changes from rushed producers. Scabbing is another potential roadblock. American writers have to be in the WGA to be staffed on major productions, but Brits, Canadians and other foreign nationals could fill empty slots. Bakish hinted at this possibility: “We have offshore production, which we’ve been moving to leverage.” This strike will be about more than just fictional characters. It raises personal and collective questions about consumption, solidarity and justice.

Ultimately, the WGA strike is sure to mark a paradigm shift in the streaming era. If the 2007-2008 movement is any indication, the 2023-2024 TV/film season could alter plot lines, season lengths and even the types of shows that get greenlit for the next decade. In this age of the endless scroll, it will be up to viewers like you and me to decide which show or movie to press “play” on when studios and writers make those changes.