“God gives each of us a purpose. For a horse, it’s to run across the prairie. For a cowboy, it’s to ride.”

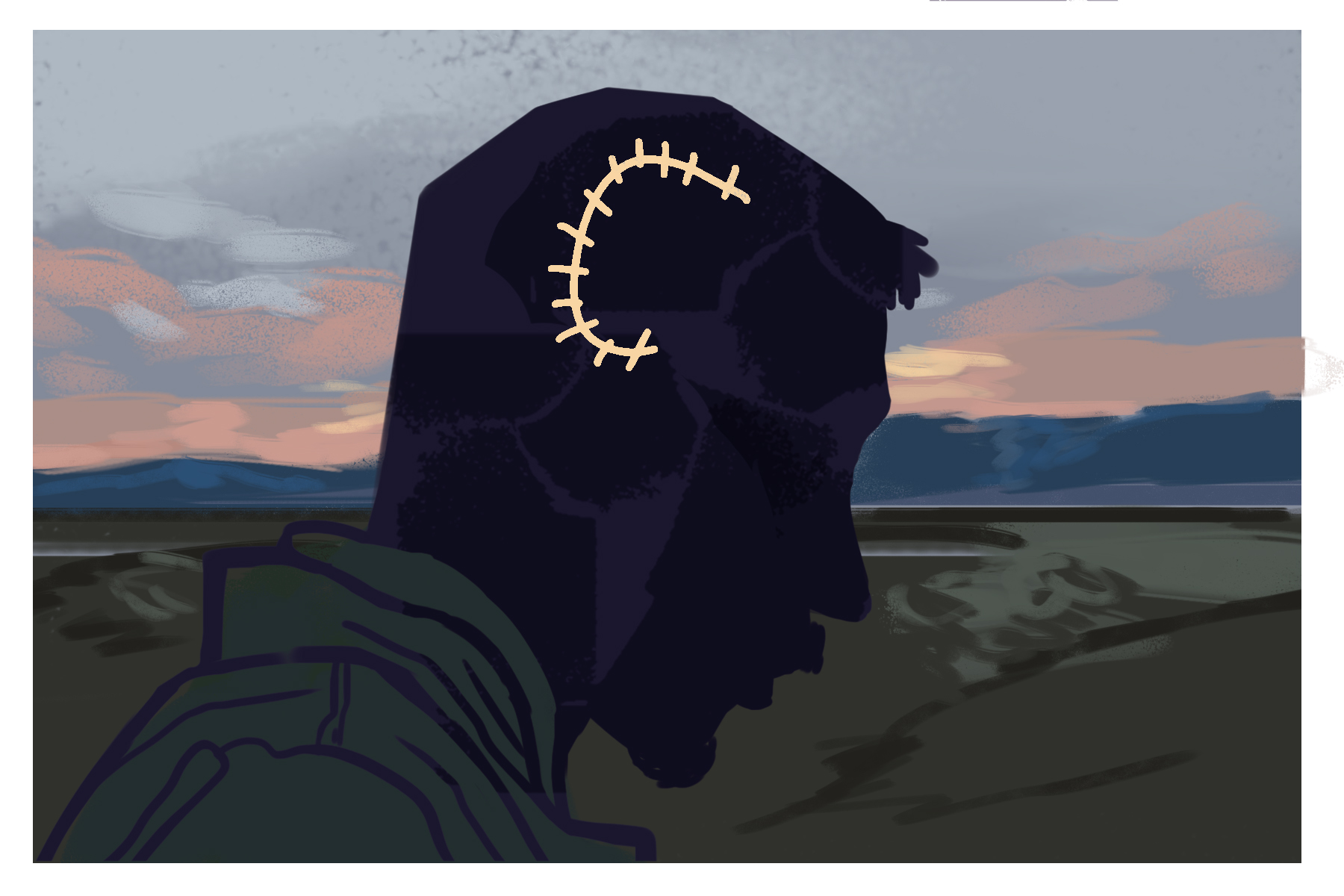

This is the thematic mantra of Chloé Zhao’s “The Rider,” a small but extraordinary film about a young cowboy, Brady Jandreau, who is tormented by his circumstances after a rodeo accident leaves him with a traumatic head injury and a doctor’s prescription that he never ride again. A lush piece of cinematic Americana, “The Rider” powerfully diagnoses Brady’s supposed purposelessness as a crisis of masculine identity.

At the heart of the film, there is a reckoning. Brady struggles to find things to do to distract him from his previous life, but everything is a stark reminder. He cleans his riding gear. He stares at old videos of himself on horseback. He heads out to the rodeo to watch his buddies do their thing. It’s painful to see someone be stripped of their calling in a split second, but even more painful to watch them fall into a cycle of recklessness and disregard for their own well-being. Unable to ride and unlikely to fulfill his dream of being a rodeo star, Brady feels emasculated and lashes out.

“The Rider” presents Brady’s relationships with dual purpose, initially using them as the bedrock for Brady’s hardened demeanor until his loved ones are convinced that he has grown overly reckless. His friends encourage him to get back to the rodeo as soon as he can, egging him on without understanding the extent of his injury.

Brady has an especially difficult relationship with his widower father Tim, an alcoholic and gambler whose degenerate habits leave Brady and his younger sister Lilly fighting eviction. This constant push and pull between Brady and the elder Jandreau, who seems to be the only mainstay older male figure in his son’s life, signals something deeper about Brady’s conflation with manhood and riding.

Tim’s selfish spending prompts him to sell Brady’s beloved horse Gus. “It’s not like you can ride anymore,” he taunts Brady bitterly, who in turn attacks him in anger. When Brady tells his father one day that he’s going to the rodeo to ride, escalating into an argument, Tim’s final rebuttal is, “Go kill yourself, then.” For all of Tim’s faults, these moments somehow feel less like heartless cuts and more like the biting words of a man concerned for his scared, reckless son, but unable to properly sympathize.

Throughout the film, Brady tries a lot of different things to make himself feel big again. He picks fights, he rides when he’s not supposed to, he ignores his doctor’s warnings. What each of these acts of defiance has in common is a desperation to regain some sense of a masculine identity and a desire to fill empty time with grand gestures. In one scene, he wrestles with a fellow rider, but what starts as a playful fight turns into an angry need to compensate. It’s a way for Brady to assure to himself, even if it means hurting a friend, that he is still physically capable in a tangible sense.

Brady’s contempt for his circumstances slowly shifts as even eventually the friends and father who’d once teased him for his incapacity grow worried that he’ll hinder his journey to full recovery. His head injury worsens; it manifests physically and mentally, but each kind mirrors the other in subtle, effective ways.

His partial hand seizure, in which his hand suddenly clenches at random moments, is both a real reminder of his existence on the sidelines and a metaphor for his paralyzed mind. He can’t let go of his passion for riding no matter how painful it is to be kept from it. The grizzled scar that runs across Brady’s scalp eventually fades to pink, and his hair grows back to conceal it, but it’s still there when he brushes the tresses back with a hand, as he often does.

This newfound vulnerability actually fortifies a few of Brady’s other relationships. He often visits his best friend and mentor Lane, a once-leading cowboy who suffered a fate far worse than Brady’s, and who now exists as both a cautionary tale and a pillar of strength. Likewise, Brady has deep affection for his sister Lilly, a young woman with autism whose curious nature leads Brady a little closer to answering his own existential questions.

Perhaps even more special to the story and to Brady’s predicament are the relationships he has with horses, and what they say about him at any given moment during his recovery. The first shot of the film is of Brady’s white-maned horse Gus, a gorgeous creature that exudes a hybrid of masculinity and femininity.

If viewers are to understand correctly, these animals are very much a part of Brady, often paralleling his own spirit. The film’s best accomplishment is in these scenes with the horses where Brady at his most truthful: sensitive, loving, internally feminine. He contrasts that with his outward performance of brutal masculinity, where his anger takes center stage and he is self-destructive in protest of whatever divine blueprint has set him up for such humiliation.

Brady’s own assessment of his life, juxtaposed with that of a horse, is striking. As Brady explains it to his sister, if the accident that happened to him had happened to a horse, the horse would be put down. “But I’m human,” Brady says, so he’ll live, even without any real purpose. This hypothesis is proven true when one of Brady’s beloved horses injures its leg and must be put down. The difference is that Brady himself closes the door to renewed purpose, unable to accept his life as anything other than the way it was before his accident, preferring to be like the horse.

“The Rider” is a beautiful filmic journey of regaining identity so organic in its character study that it should come as no surprise that Brady is a real person — last name Blackburn — and that nearly every person who surrounds him in the film is playing a fictional version of themselves. Zhao never asks too much of her actors because she does not need to; they exude the complex humanity of their own lived experiences, but Blackburn himself is the standout, channeling the pain of his ordeal through broken stares and tired eyes. Most important of all, the connection seen in the film between Brady and his horses is real. He knows them so well, it’s no wonder he feels intertwined with their souls.

The far-reaching grasslands where Brady lives are both a gorgeous setting and hold a larger meaning for Brady. There is so much land for him to explore on horseback, the plains stretching out in every direction, teasing him that the very thing which once brought him boundless joy now keeps him tethered, stuck and weakened. “The Rider” reevaluates Brady’s relationship to riding and what it means to his identity: is it about being a man? Is it about physical strength and skill? Or is it a matter of dreams coming and going, the aftermath of something that feels like the end of the world but ultimately isn’t?