Henry James’ “The Turn of the Screw,” a late-19th century novella, operates according to precepts of Gothicism: Dark, foreboding settings and deep emotions stand prominent. The imagery referenced in the title does not escape the work’s basic concepts, where tension and strain gradually crescendo as the story reaches its climax.

My playthrough of Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us Part II felt strikingly similar to this work of literature, not in terms of plot, but in how it works to constantly build and break down audience pathos through mood and setting.

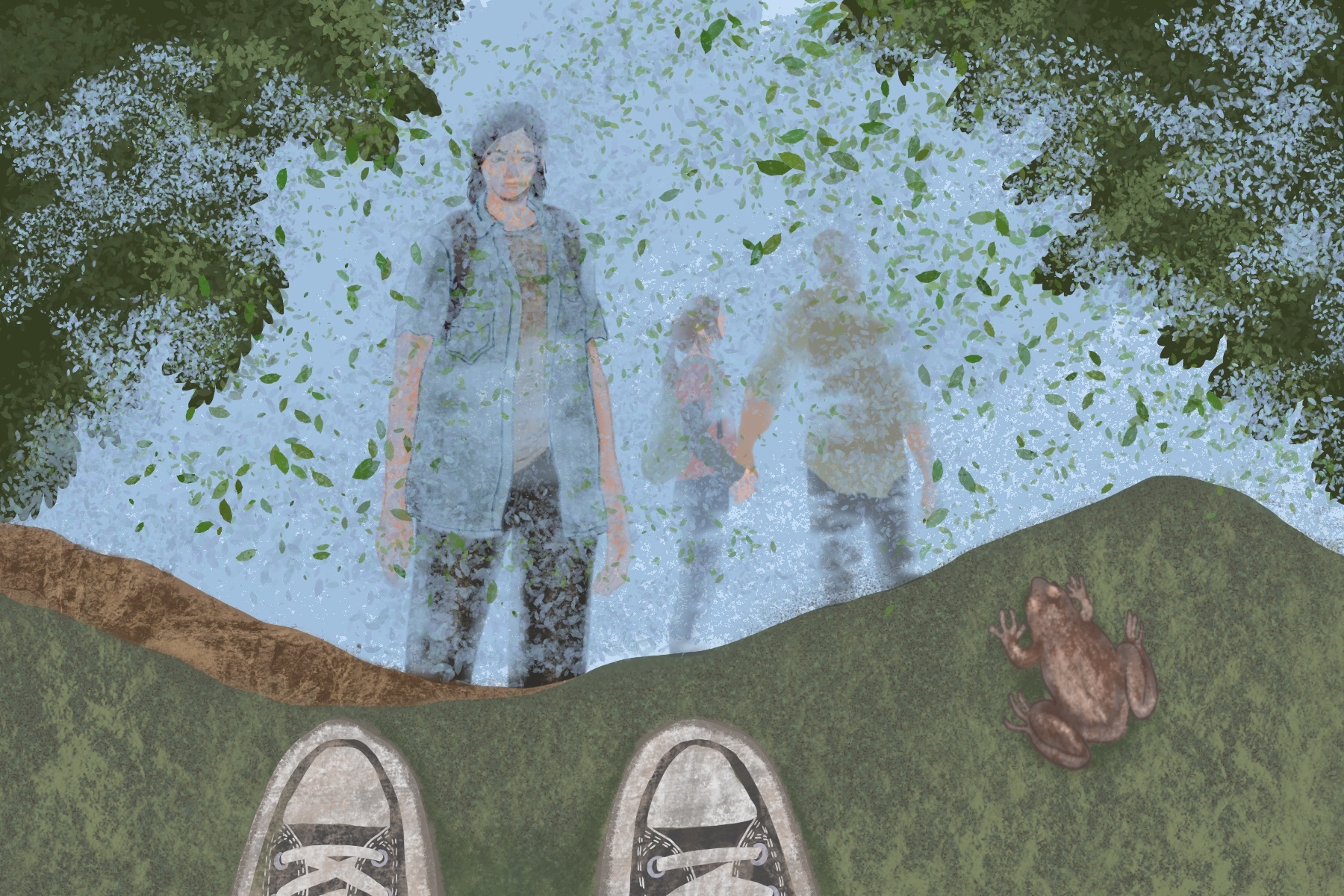

Ellie, the game’s leading protagonist, traverses an overgrown Seattle years after a devastating outbreak tarnishes much of the global population. Survivors are left to fend off fungal-induced zombies and the remaining, invariably dangerous human factions. At a very basic level, Ellie’s goal is simple: revenge.

To fully understand the stakes in The Last of Us Part II, familiarizing oneself with the first installment is a necessity. Joel, a bereaved father, travels across the United States while protecting 14-year-old Ellie, who has an immunity to the deadly Cordyceps brain infection. Hired by a militant faction, Joel must deliver her to doctors who can allegedly form a cure as a result of Ellie’s abnormality.

As the pair treks further into their journey, a paternal relationship blooms, and Joel no longer sees the teenage girl as mere cargo. Rather, he sees Ellie as the daughter he lost two decades ago. During the game’s climax, Joel chooses to save Ellie, despite the necessity of her death to develop a cure.

This question of morality versus ethics expands in the sequel, forcing the player to understand the consequences of Joel’s decision five years after the fact. The Last of Us Part II works to undermine our understanding of the first game’s protagonist, challenging notions of retribution and revenge.

Longtime fans watch as the game redefines a man who once stood as a genre-defining hero. Yes, good people do bad things, but the story belabors a point that bad people can do good things too.

Reconsidering acts of violence

After seeing blood in a video game for the first time, I convinced my 9-year-old self nothing of the sort would happen again. I vividly remember sitting on the edge of my neighbor’s bed with a few friends on a summer day, shifting to keep the duvet from sticking to our thighs. Though only one person controlled the avatar, everyone dutifully watched and cheered when he sprayed bullets into moving traffic, leaped from the lip of a tall building or decided to rob a bank.

This onslaught of graphic violence triggered a thought that I still ask myself when playing video games: Where are they going with this brutality? Naughty Dog takes such a question and mercilessly runs with it.

The first few hours offer the player an inward look at what life looks like for Ellie, now 19 and hardened by her journey in the first installment. She spends much of her time like any young adult in the settlement would — flirting with her girlfriend, engaging in snowball fights and patrolling the frozen landscape of Jackson, Wyoming. Ellie struggles to comfortably interact with Joel knowing that he stripped her of any opportunity to make her life worth something at the end of Part I.

Abby, the newly-introduced antagonist, arrives in Jackson to invert this idyllic way of life. Since spoilers are inevitable, I’ll broach the plotline vaguely: Ellie watches as Abby murders Joel, and the player must submit and watch this excruciating moment alongside her. When Ellie sets off to Seattle for revenge, the controlled tension directs the player to share her same motives.

As Ellie fights and kills her way through the overgrown city, developers not only breathe life into the landscape, but also ensure that foes are incredibly authentic. Each time the player fires at unsuspecting opponents, be it members of the determined Washington Liberation Front or the cult-adjacent Seraphites, we hear cries when an enemy’s body is discovered.

Each CPU character has a name, including dogs. So, while Ellie relentlessly takes out one person after the other, players recognize a greater anxiety, one that forces them to see each enemy with empathy. Transcending the assumed formula of shoot-and-kill games, Naughty Dog tacks on a controlled move that demands remorse for every person you kill.

Writer and director Neil Druckmann noted in an interview with Kotaku that “the player [should] feel repulsed by some of the violence they are committing.”

This emotional resonance heightens halfway through The Last of Us Part II when players must play as the game’s comparative antagonist, the murderer of Joel. For nearly 15 hours, the audience works to hunt down Abby. Now, they must assume her role.

Understanding the “twist”

Druckmann shared that the studio sought to “[make] a game about the cycle of violence and we’re making a statement about violent actions and the impact they have on the character that’s committing them and on the people close to them.” When forcing the player to follow Abby’s story, this narrative authority broadly carries a larger message about our understanding of heroism in video games. Concepts underpinned by violence teach us that anything beyond the aiming reticle qualifies as evil, or the “wrong side” of the fight.

Delving into the alleged enemy’s backstory helps the player realize how groupthink informs an understanding of a person, so by the end of The Last of Us Part II, we see both Abby and Ellie for who they are as people rather than defining them by their motives.

At the outset of Ellie’s journey to Seattle, I wanted nothing more than to avenge Joel, a character who has stayed with me since his introduction in Part I seven years ago. This loss resonated when I watched his brutal death unfold during my playthrough, and it still lingers. Yet, when Ellie finally reaches a moment where a chance for revenge rests in her hands, she lets go. It’s as if the game aims to speak to the player, saying: You should do the same.