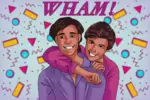

Positive representation of queer people on-screen is something activists have been fighting for, for decades, and yet somehow, decades later, depressingly few shows on major networks have explicitly queer protagonists. Enter “Q-Force,” an adult-animated spy comedy in the vein of “Archer” that centers on an eponymous team of superspies who are constantly sidelined by their superiors because of their sexualities. Many commentators have expressed disapproval of the show since the June release of its first trailer, which suggested a show filled with obvious jokes based on stereotypes devoid of substance. Now that the show has been released, does it live up to its negative publicity? Fortunately, surprisingly, no. But “Q-Force” is still nowhere near the breakthrough series its creators have promoted.

Steve “Mary” Maryweather (Sean Hayes) is a top-ranking recruit in the American Intelligence Agency (AIA), but his career is ostensibly ended when he comes out as gay at his induction ceremony. His prejudiced superiors proceed to assign him to West Hollywood, known for its large gay community and lack of any sort of potentially taxing work, with the rationale that he is too “soft” for traditional fieldwork.

Ten years later, Mary leads a team of gay and lesbian spies dubbed “Queer Force,” whose members have all suffered similar humiliations and have never been given meaningful assignments. There’s Stat (Patti Harrison), a lesbian and clearly trans-coded hacker; Deb (Wanda Sykes), a lesbian mechanic in a committed relationship whose partner doesn’t know she’s a spy; Rick Buck (David Harbour), Mary’s straight rival from the academy whom AIA brass added to the group to monitor them; and — last and least — Twink (Matt Rogers), a drag queen and master of disguise. Together, Q-Force solves cases the AIA feels are undeserving of their attention, and in the process occasionally save the city and sometimes the world.

The initial trailers for “Q-Force” were near-universally panned for depicting a program appearing to be based solely on queer stereotypes and overall lacking self-awareness. Fortunately, the trailers didn’t tell the full story of the 10-episode first season. The show is mostly very good at using stereotypes to highlight their idiocy and baselessness. Unfortunately, the show sometimes fails to commit, resulting in embarrassing missteps with jokes that don’t land or characters who become incredibly unlikable because of their unaddressed personality flaws.

The primary example of this is Rogers’ Twink, whose name is very on the nose. (“Twink” is a term for an effeminate gay man.) Twink’s character is the least developed among the group’s and is the most stereotypical of a gay person on-screen since John Michael Higgins’ intentionally camp Scott Donlan from 2000’s “Best in Show.” Twink is petty and self-absorbed, with no redeeming qualities, and his character is in no way helped by the show’s script.

Though the sense of humor in “Q-Force” seems dated, it is by no means offensive, and its representations are quite positive. It’s still incredibly rare to see loving queer couples on screen, so it was a welcome surprise to see Deb’s interactions with her wife, which are incredibly wholesome and a welcome departure from the poor handling of sensitive subjects shown by other parts of the show.

The recent spate of popular so-called adult animated shows share many qualities, from their simplistic animation styles to their sense of humor. “Q-Force” is unfortunately no exception, as it falls directly into the genre’s cliches. The most egregious of its sins is its script, whose humor relies mostly on profanity, sexual innuendo and pop culture references. In moderation, such elements are perfectly capable of working, especially when used alongside a compelling overarching story.

Yet “Q-Force” fails to make any of these elements work together. Each character shares many of the same personality traits; most noticeably, they’re all witty in that very Marvel-esque, Gen Z way, ceaselessly spouting references and sex jokes in an attempt to be edgy. As a result, these characters seem shallow, even as they’re supposedly dealing with serious situations.

The funniest moments occur when the show commits to the absurdity of its premise, like when a maniacal billionaire supervillain attempts to crush a room full of naked, musclebound men into pulp in a nightmarish machine he dubs the “Jock Presser,” trying to harness the bodily chemicals that make them “virile,” or when a deranged monarch uses mind-control party hats to create an army of gay people at a Pride parade. Unfortunately, such moments are few and far between.

The show’s wild shifts in tone from serious to campy are only sometimes effective, especially when they concern the overarching plot of an AIA conspiracy involving prior teams of queer agents. It’s a surprisingly dark and relevant plot, and yet the characters who uncover it express only mild dismay that their own agency is committing such atrocities (and in the end they easily make amends with their superiors, even having condemned their actions mere moments before).

What makes it all even more confusing is that “Q-Force,” while selling itself on its representation of queer characters, fails to fully represent the queer community. There is no explicit bisexual or transgender/nonbinary representation; equally as baffling is that Stat, who is portrayed by a transgender actress and is implied to be trans, is never stated to be as such in the show. Coupled with underwhelming writing and humor, it seems the show isn’t aimed at a queer audience at all, but is merely another display for a public unlikely to appreciate the show’s subversion of stereotypes.

For all of Netflix’s claims of the show’s commitment to representation, “Q-Force” is not nearly as groundbreaking as it would clearly like to be. Its predictable style of humor has lost its charm, and while its characters are mostly likable, they still fall into mainstream stereotypes of queer people. A theoretical second season ideally would resolve these issues but judging by its reception and lack of publicity surrounding its release, a Season 2 would appear improbable.