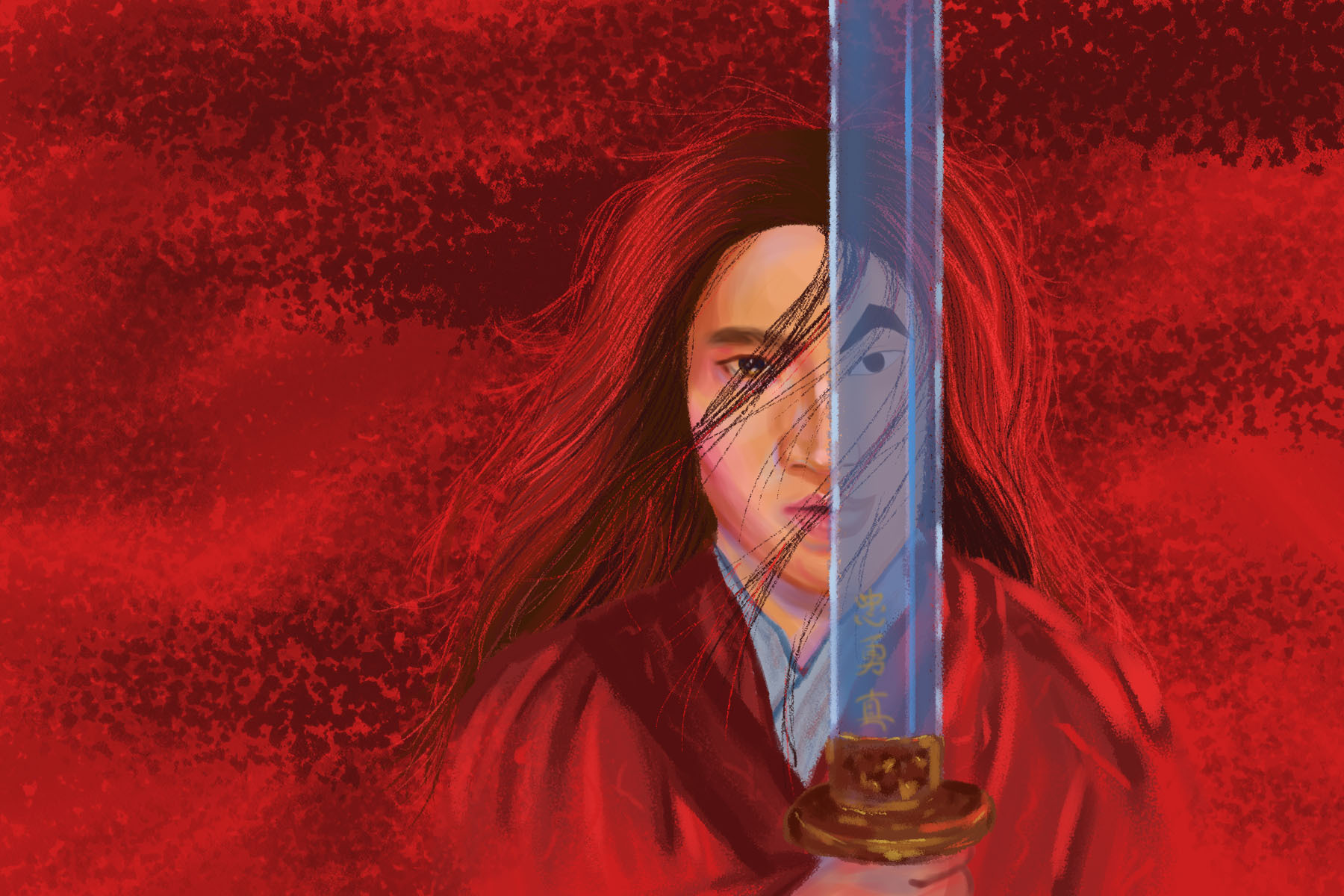

While watching the newly released live-action adaptation of “Mulan,” my skin broke out as I spent the excessively slow hour and 55-minute run time praying that the movie would meet my expectations. As one of the few depictions of Asian women on screen during my childhood, the 1998 Disney-animated film was a staple to my identity as a young Asian American. Other than the ditzy character London Tipton from Disney Channel’s “Suite Life of Zack and Cody,” there was little representation of Asian Americans in the media.

Even though I didn’t fully understand what I was experiencing as a child, I knew it was important that I resonated with this strong female protagonist that looked like me. Mulan in the animated version was brave, funny and charismatic. With her faithful and adorable sidekick, Mushu the dragon, the cartoon became a source of inspiration and pride for my Chinese heritage.

Unfortunately, the childish charm of Mulan did not translate at all to the live-action version. When I heard that Disney was releasing a live remake, I was anxiously excited to see a staple of my childhood revived. In the back of my head, I prayed that the new “Mulan” would become a type of feminist “Black Panther” movie for the Asian American community to rally around, a sort of Hollywood emblem for diversifying narratives on screen.

However, I was sorely disappointed. It is partially my fault for going in with expectations: Though the movie lacks humor and “relatable” characters, it does represent an interesting depiction of Chinese culture to a mostly Western audience, albeit flubbing some of the Chinese cultural references. With its overly explicit announcements of traditional Confucian beliefs, the characters remain relatively two-dimensional and underdeveloped, symbols of a culture rather than fully formed people.

Back in 1998 when the Disney-animated “Mulan” came out, many Chinese viewers were confused and appalled at the Americanization of the traditional folk tale, with people complaining that “Americans don’t know enough about Chinese culture.” The strong individualistic Hua Mulan goes to battle to fight for herself and her rights more than for the sake of her father, a selfish choice that reflects more on the American Dream than on Chinese cultural norms. The jive-talking dragon Mushu is also an extremely American addition to the original Mulan folktale.

In this new version of “Mulan,” the movie references the tenets of Confucianism, emphasizing, to the point of redundancy, themes of honor and filial piety. Confucianism is a social and political philosophy founded in the Zhou dynasty that underlies much of Chinese culture. The central principles of Confucianism outline basic civic duties and define roles in society. Though China has had centuries of history since Confucius, the values outlined in Confucianism still heavily influence cultural norms in China today. An important idea that “Mulan” riffs off of is filial piety, or loyalty to family and parents, as well as loyalty to the government.

Though her paranoia about being found out as a woman is reasonable, Mulan lacks humor and never seems to relax. Most of her spoken lines have a strange way of constantly announcing Chinese customs of filial piety instead of giving insight on her personality, leaving her character undeveloped and unbelievable.

In a typical movie, the cultural customs would be quietly acknowledged and shown through action rather than spoken out loud. Yet in “Mulan,” if you took a shot for every time “bringing honor to your family” was mentioned in the movie, you would surely die of alcohol poisoning. Mulan is fiercely loyal to her family, to the point where it seems that her entire personality is dedicated to just that.

This new Mulan is all of the original Disney character’s strength and bravery, but completely lacks joy and humor. The meek attempts at comedy come off as cringy and awkward, which is partially the fault of the awful screenwriting and uncomfortably slow pacing. The movie is too serious for young audiences and never reaches a level of depth to satisfy older viewers.

Another aspect of the movie that has inspired backlash is its application of “chi,” traditionally spelled “qi.” In traditional Chinese medicine and martial arts, chi is concerned with the flow of energy through the body, but in the movie it is made out to seem curiously similar to “the Force” in Star Wars, like some sort of magical power.

Not only is chi portrayed as mystical, it brings into existence a completely new character, the witch Xianniang, who’s a terrifying substitute for the comic relief of Mushu from the original animated film. The subplot involving Mulan and Xianniang verges on a feminist lesson about women supporting women, but falls short and leaves viewers confused about a possible unspoken, homoerotic love story between them.

Nonetheless, the beautiful shots filmed in China and New Zealand, the experimental editing and wuxia-inspired fighting scenes are intriguing. As a cultural object that represents a Western attempt to appeal to Chinese traditions, this movie is interesting, but not accurate. With its plot holes and bland characters, “Mulan” feels more like a blueprint for a great movie, a draft that needs to be edited and reworked a bit to create more believable characters and bring back some of its original light-hearted charm.

I am disappointed by the film’s failure to portray Asian characters as full, complicated characters. Mulan is strong, and reflects traditional Chinese beliefs, but in the movie, she is only that. She barely has a believable internal life. It is important to show minority groups on-screen as real people instead of stereotypes of Chinese culture. I wouldn’t put “Mulan” up there with other films like “Crazy Rich Asians” and TV shows like “Fresh Off the Boat” that are successfully working to close the gap in representation of Asian Americans in the media. “Mulan” sits as a symbol of the work that needs to be done in cross-cultural conversation between Eastern and Western cultures.